27/3/2009

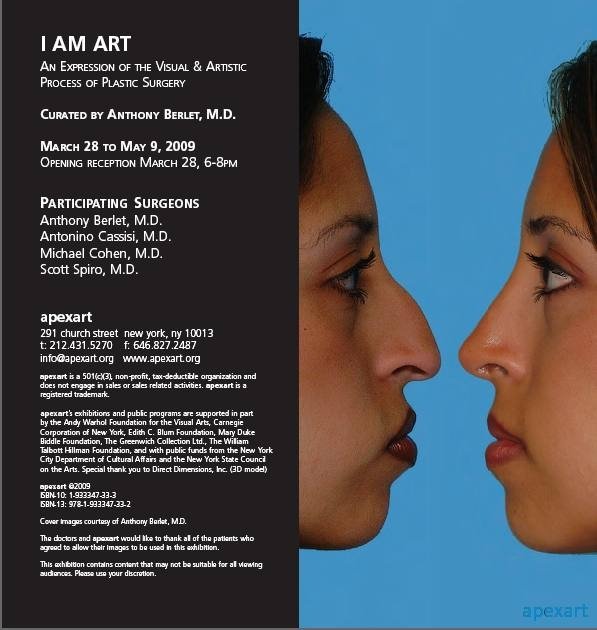

I am Art

Apexart, New York

An Expression of the Visual & Artistic Process of Plastic Surgery. Leon Dufourmentel, a pioneer in plastic surgery, said in 1948, "...If I went to Picasso for my portrait, he would probably make me a monster and I should be pleased because it would be worth a million francs. But if Picasso came to me with a facial injury and I made him into a monster, aha, he might not be so pleased." Curated by Anthony Berlet.

Curated by Anthony Berlet

Presenting work by Anthony Berlet, M.D., Antonino Cassisi, M.D., Michael Cohen, M.D., Scott Spiro, M.D.

Leon Dufourmentel, a pioneer in plastic surgery, said in 1948, “...If I went to Picasso for my portrait, he would probably make me a monster and I should be pleased because it would be worth a million francs. But if Picasso came to me with a facial injury and I made him into a monster, aha, he might not be so pleased.”

This quote expresses the view of the exhibition that plastic surgery can be a most challenging art form, since a surgeon’s materials are not canvas or clay, but rather the human body. However, not everything in plastic surgery is necessarily art. Some procedures are rote, technical mechanics, operations that can be taught to almost anyone and, if they are performed as they are taught, the results will always be the same. But those same routine surgeries can also become something that requires a great deal of artistic skill depending on the patient’s need. A facelift is a good example. If one understands the anatomy, performing a facelift is a basic reversal of the process of aging. Over the years, the procedure has changed from simple skin lifting to complex plane lifting techniques, where incisions are made and various degrees of undermining of the skin are performed, resulting in the deeper layers of the face being lifted. While this is a routine surgery and there is nothing particularly creative in the basic process, finding the proper vectors of pull and reestablishing lost volume in the face does elevate it to an art. Occasionally there is additional pathology, at which time a surgeon has to rely on his or her creativity and experience to solve these problems. When we must borrow tissue from other areas, hide scars in natural lines that already exist, or create something from nothing, the more creative the surgeon, the less obvious and apparent the procedure.

There are some procedures that are inherently creative, whether because of the anatomy involved or the surgical plan, and always because of the fact that the surgeon is working with parameters that are bounded by blood supply, type of tissue, and the quality of skin. Rhinoplasty (a nose job), for example, can be an extremely altering procedure requiring a keen artistic sensibility in the surgeon. This is often considered one of the most difficult procedures to teach in plastic surgery because each nose is unique, sharing only the similarities of having a bridge and a tip. Older surgical techniques involved shaving off the hump, cutting down the cartilage and then breaking in the walls of the nose, leaving it lacking structure and support. This was standard procedure and it was done relatively inartistically by plastic surgeons for decades, leaving many patients unable to breathe through their noses. However, modern plastic surgery addresses rhinoplasty in a much more creative and functional manner. Noses may have a bulbous tip, or a large hump, or a wide bridge with essentially no hump, and to recreate and reshape such a nose becomes an artistic process with an architectural fundamental principle of “form follows function”. The surgeon must reestablish a bridge that is contiguous by reducing a dorsal hump and rebuilding from cartilage from within before infracturing the bones. In order to design a tip, a stable tripod must be created out of the existing anatomical structures. The surgeon has to sculpt it from one side to the other, shorten it, shape it, actually carve the cartilage and score it to help it bend in certain places, and then secure it with sutures and sometimes additional cartilage. For this, a surgeon must have an innate three-dimensional vision in order to create a defined tip that may be vastly different from what one is starting with. The surgeon must also reduce the nose in a proportion that fits the uniqueness of the face and adheres to the “rule of thumb” by da Vinci (locating the nose at one-third of the face). The surgeon must then streamline the nose so it balances with the remainder of the face to create a pleasing aesthetic. Interestingly, sometimes this also involves adding a chin implant to achieve balance so that the focal point of the face as a whole does not suddenly point towards the nose. In the end, all aspects must come together to create a new proportion and balance to the face, one that is defined as an aesthetic within our society.

Another example is breast reconstruction from cancer. Today, we perform “immediate breast reconstruction” where the breast is rebuilt immediately following a mastectomy (breast removal). The general surgeon leaves most of the skin envelope into which the plastic surgeon places a breast implant or tissue from another area of the body. While this requires skill and experience, it has limited creative potential. On the other hand, there is a far greater challenge when the patient has had a complete mastectomy and has been treated with radiation and chemotherapy. Not only will the patient’s chest now have an unsightly crater from the breast removal, but her body has also been visually ravaged from the drugs, radiation and scarring. The plastic surgeon must rebuild a breast by establishing a new skin envelope, creating something from nothing because the radiated tissue must be cut away as poor blood supply generally limits its use. Tissue with its own blood supply must be fashioned using a paddle of skin and fat from the patient’s belly based on a muscle “leash”. The paddle of skin is shaped into a breast that matches the other breast, in a constant balancing act so that the final result will be symmetrical and natural in appearance. This is a creative process that extends to almost all levels. The surgeon uses a perfect blend of reconstructive and aesthetic techniques to reestablish a balanced bosom and take advantage of the donor site to create a rejuvenated abdomen. Liposuction can then be used to fine-tune the sculpture of human flesh back into a woman who is no longer just surviving but now “living”.

For surgeons, some of the most artistic procedures are found in microsurgical techniques where tissue is transferred from one part of the body to another based on establishing a new blood supply. This allows the surgeon to reestablish tissue in another location that can be rebuilt into something else; for instance, in a situation where a tumor has been cut away in the mouth, a leg bone can be transplanted in the face to recreate a mandible bone, along with a paddle of skin that is cleverly placed to recreate a new internal lining of the mouth. This is all dependent on the blood supply, and the new tissue is sewn into arteries existing in the neck whereas originally the arterial blood supply came from the leg. In such situations, surgeons must have the knowledge and the sensitivity to be able to harvest the bone with profound knowledge of the anatomy and limited donor deformity while also reshaping the bone to emulate the mandible.

The initial patient evaluation and the surgery plan requires the studied eye of a trained artist. Leonardo’s anatomical drawings and investigations are not dissimilar to the scrutiny of this process. The execution can best be described as a well-choreographed ballet of many different steps. Through this dance of medicine and art, science and aspiration, surgeons seek an outcome as beautiful as any painting or sculpture. Every day, we strive to outdo Pygmalion. Is perfection possible? We know it’s not, and yet, that’s our calling. We work with terrible constraints, not the least of which is the subjective nature of art itself. Nowhere are human feelings more various and more complex than in perceptions of the body and of the self. We are, all of us, acutely aware of how others see us. Physical things become emotional things. Some patients want to regain the beauty of their youth; others require reconstruction after illness or physical trauma; and still others seek a means to correct natural deformities. All hope to be able to look in the mirror and see what they expect to see. The restoration of confidence and self-esteem that surgeons witness in post-operative patients is an art form in its own.

Our field is sometimes associated with excess. This exhibition aims to convince you otherwise. For each individual committed to our charge, the stakes could not be higher. This show conveys the great care with which surgeons diagnose, counsel, prepare, execute and maintain our artistic creation, with vision, clarity, passion, ingenuity, compassion and, yes, art. Certainly there are pictures of the grotesque scary traumas and cancer defects. There are also pictures of the beauty that is the human form, in all of its various shapes and sizes. As surgeons, we sometimes have to take two steps backward to take one step forward in generating a plan to bring tissue from one part of the body to another part of the body, essentially bringing the clay to the sculptor, where it will be shaped and molded, created into what it needs to be for the patient. In the gallery space, you will have a glimpse into our world, which is never our world alone. Ours is truly the most intimate, the most personal, of arts. When we are finished, the product of our labors can turn to us and say, “I am art.” That, at least, is what we strive for.

© Anthony Berlet, M.D.

The doctors and apexart would like to thank all of the patients who agreed to allow their images to be used in this exhibition.

This exhibition contains content that may not be suitable for all viewing audiences. Please use your discretion.

berletplasticsurgery.com

antoninocassisi.net

drcohenplasticsurgery.com

drspiro.com

apexart’s exhibitions and public programs are supported in part by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Edith C. Blum Foundation, Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, The Greenwich Collection Ltd., The William Talbott Hillman Foundation, and with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the New York State Council on the Arts. Special thank you to Direct Dimensions, Inc. (3D model).

Opening reception Saturday, March 28, 6-8pm

Apexart

291 Church Street - New York

Free admission