Aleksandr Rodchenko and Liubov Popova

dal 19/10/2009 al 21/2/2010

Segnalato da

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia

19/10/2009

Aleksandr Rodchenko and Liubov Popova

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Defining constructivism.

This exhibition focuses on Aleksandr Rodchenko and Liubov Popova’s work from

1917 to 1925. In this period of upheaval lasting less than a decade, Russia moved

from the urgency of the revolution to the establishment of the Soviet state, from

pure pictorial abstraction to the definition of Constructivism. More than a

movement, the latter was an artistic ideology applicable to many types of

creation, including graphic and industrial design, sculpture, painting, film and

theater, among others.

The October Revolution marks the moment when the emerging power of the

Soviets transformed artistic debate into a complex reflection on working

conditions, the nature of production and the elements involved in construction (of

an object, a society, the “new citizen,” men and women). In this new model of

society with universalist aspirations, the arts were not a peripheral element; they

played a central role in its ideological, political, economic and philosophical

debates.

There are two key historical moments in the definition of Constructivism as an

artistic movement: 1917, when the Bolshevik revolution began; and 1925, when the

International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts was presented in

Paris, just a year after Lenin’s death. While the first event was a major catalyst for

experimentation, the second marked the international consolidation and

popularity of many of the ideas developed by Rodchenko and Popova. But it also

marked the movement’s demise, paralleling the end of the revolutionary process

and the beginning of the oppressive Stalinist regime.

Bolshevik ideology implied the elimination of the Bourgeois way of life in all its

manifestations, and so, Constructivism was born of destruction—the death of easel

painting. The clearest expression of this purge is Rodchenko’s 1921 triptych, Pure

Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure Blue Color, a definitive tabula rasa that

determined the end of a world, beginning with the disappearance of the two-

dimensional elements that had represented it. This gesture was radically

iconoclastic in a time and place where the religious icon was a sign of identity. As

Popova put it: “representation resulting from artistic production is an objective that

has met practical needs from the Renaissance until very recently (easel panting,

icons, frescos, the sculptures located in public places, courts and palaces,

architecture as a visual object, and so on).”

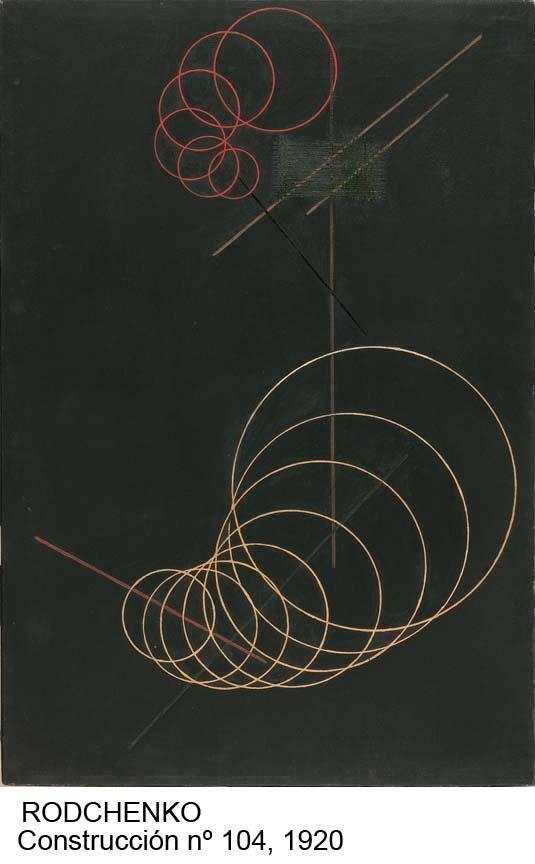

In its rejection of any form of illusionist representation, Constructivism’s earliest

period was characterized by extremely hermetic abstraction driven by an interest

in texture, the psychological effects of color, and geometry in movement. This first

period is exemplified by both Rodchenko’s Black on Black (1918) series, in which

color is eliminated in order to focus attention on the pure pictorial surface; and

Popova’s geometric figures in movement, which are intensely colored and

constructivist in their inclinations. Both series owe much to the radicality of

Suprematism—embodied by Malevitch, who first brought the avant-garde to

Russia—and the dense theorizing of Kandinsky, who set the bases for European

abstraction before being called to join the first Bolshevik artistic bureaucracy.

The maxim, “only paint exists,” that underlies these early artworks would soon be

contradicted by the interdisciplinary tendencies that characterized the

movement. Graphic works allowed it to reach a broader public and also to

distance itself from the idea of the artwork as unique and irreproducible. From the

first drawings and engravings we can already see the application of constructivist

principles to disciplines such as architecture and industrial design.

The 1920s began with the presentation of the INKhUK, an institution dedicated to

thinking and dialog about artistic creation where the theoretical underpinnings of

Constructivism emerged: on one hand, the socialist concept of participation in

production, and on the other, the resolution of the “composition/construction”

debate in favor of the latter. Unlike Expressionism and early Central-European

Lyrical Abstraction, which promoted the idea of pictorial space as individual

expression, Constructivism activated a series of political strategies to change the

new human being’s mental and material structures.

That is when Rodchenko

reduced his work to its essence, with the line as its main element, a more limited

palette and the use of new supports, including sheet metal and cardboard.

The impact of the 5 x 5 = 25 exhibition, which many consider “the last exhibition,”

marked the beginning of new creative applications of what had been learned in

the limited terrain of two-dimensional art.

Traditional painting was abandoned in

favor of formats more closely associated with the idea of the project, such as

drawings and models. Sculpture had already been rejected in its classical

conception, freed of its physical limits and distanced from its traditional “archaic”

and commemorative associations. In the search for new space, the floor and walls

stopped being limits or supports for three-dimensional pieces. They were now hung

from the ceiling, including Popova’s Dynamic-Spatial Constructions (1920-1921)

and Constructions in Space (1920-1921).

In 1921, Constructivism became the corporate image of Lenin’s New Economic

Policy through Rodchenko and Popova’s publicity, propaganda and educational

works (mainly posters and textiles). There, the ideological message is marked by

pure geometry, flat colors and unadorned lettering—forceful elements of, and for,

immediate communication that have left an indelible mark on the history of

design and publicity.

As it entered the field of design, art served productivity, becoming a project and

establishing a definitive relation with industry as the best expression of the new

human being. In keeping with the slogan, “new everyday life,” the public space

was flooded with posters that Rodchenko created in collaboration with the poet,

Maiakovsky, while industrial and interior design promoted surroundings steeped in

ideology—visual representations of dialectical materialism. In that sense, The

International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in

1925 included a mock-up of the Workers’ Club project, the final application of

many of the disciplines with which Rodchenko and Popova had been working for

nearly ten years.

The Club was presented as the perfect setting for workers whose

leisure time would be characterized by a process of political awakening, a place

far-removed from former bourgeois comforts and designed to contain study

materials on Lenin for projections and presentations. There was to be only one

concession to recreation: a chessboard. This space intended for socialist immersion

led to the far-reaching propagation of Constructivism’s formal values on an

international scale just when it was disappearing from its native land with the

dawn of Socialist Realism.

Finally, that interest in the new art’s presence in all aspects of proletarian life found

radical expression in Rodchenko’s collaborative works for theater and film,

especially after Popova’s death in 1924. Rodchenko’s collaborations as artistic

director and designer with Lev Kuleshov and Dziga Vertov allowed him to

approach a quintessentially reproducible and applied art for the masses with

immediate ideological effects. In that sense, Vertov wanted his 1922 film, Kino-

Pravda, for which Rodchenko designed the credits, to be projected in streets and

factories, rather than in cramped movie houses.

Rodchenko’s ideas for interior

design were spread by Kuleshov’s 1927 film, The Journalist, while Boris Barnet’s

Moscow in October, also from 1927, embodied the application of his vast

knowledge of photography to moving pictures. Filmmaking exemplified the idea

of participative production (it is collective work by definition) while simultaneously

allowing the development and exploration of concepts in a visual setting not

limited by the edges of a canvas or the walls of a gallery.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Sabatini Building. 1st floor

Santa Isabel, 52 Madrid

Hours:

Monday to Saturday: 10:00 – 21:00 h

Sundays: 10:00 – 14:30 h

Tuesdays Closed