Leon Ferrari and Mira Schendel

dal 24/11/2009 al 28/2/2010

Segnalato da

Press office Museo Reina Sofia

24/11/2009

Leon Ferrari and Mira Schendel

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

The Frenzied Alphabet

Curated by: Luis Pérez-Oramas, Conservador de Arte Latinoamericano del MoMA

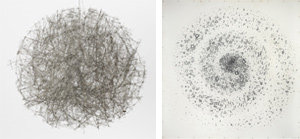

The works of Mira Schendel (born in Switzerland in 1919 - died in São Paulo in 1988) and León Ferrari (born in Argentina in 1920) have found their principal visual source in language as both writing and gesture, that is, as both verbally intelligible and purely visible matter. Even at its most silent, intimate moments, their art is imbued with the protean tumult of language’s countless faces and incarnations, from voluntary silence to aphasia, passing along the way through whisper, prayer, accusation, sermon, dialogue, quotation, stutter, shout, onomatopoeia, collage, argument, alphabet, and poetry. Both artists knew poets well—Haroldo de Campos in the case of Schendel, Rafael Alberti in that of Ferrari—and both at one time or another were poets themselves.

The early 1960s were crucial years in the development of Schendel’s and Ferrari’s work—that is, in its materialization of new and different forms—and 1964 in particular seems to have brought both artists to turning points. That was the year of Ferrari’s Cuadro escrito (Written painting), 1964, which followed a period of intense focus on drawing that led him first to the abstraction of deformed, illegible writing, then to the sophisticated but no less hermetic calligraphy of his written drawings. That same year, Schendel embarked on a phase of her practice exclusively dedicated to works on paper, specifically rectangular sheets of the Japanese paper often called rice paper. To make her drawings of this period—around two thousand of them— she used a self-invented technique, her own in both the application of the ink and the actual physical gesture. The period ended toward the late 1960s with the creation of her most emblematic objects: the Droguinhas (Little nothings), 1968-73, Trenzinho (Little train), 1965, and the Objetos gráficos (Graphic Objects), 1968-73.

In North America and Europe, these years also saw the emergence of an art form that used no single medium, or at least that could not be understood from the perspective of the qualities of a single medium or material. Instead, as Sol LeWitt wrote, this was an art form in which “the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work.” From the start, the critical writing on this work—Conceptual art—developed what would prove to be one of its essential myths, the dematerialization of the art object assumed to be implicit in it.

While language as an ideal vector of meaning is a central “aspect” of the Conceptualists’ art, Ferrari and Schendel are concerned with the “aspect” of language in the sense of its visual appearance. The works of Ferrari and Schendel describe an ingrown, interconnected language, a written materiality, language as a trembling of the hand, a shudder of the body—language that itself has shuddered, a language that voices an idiosyncratic, irreplaceable subject. Of course their art involves ideas and concepts, indeed, often, ideas and concepts in their barest state, an obstinately repetitive plundering of barely legible names, words, fictions, definitions, locutions. But these things are depicted in a physical circumstance, where the materiality of signs and symbols resonates like a dissonant, distorting echo of the ideal and perhaps fictional purity of the mind and of ideas.

Ferrari and Schendel are visual artists who never abandon the word. On the contrary: even in their most silent, empty images, they make the word the center of their work. More specifically, what is still clearer in their work than language, even when the text is impossible to identify, is writing—writing in Barthes’s sense of scription, the “muscular act of writing, of drawing letters,” in other words its radical material reduction, and the revelation of its capacity to function as a visual representation of enunciation. Their work’s guiding spirit, then, more than language, is the word itself—the word as a limitless substitute for the human voice. Ferrari and Schendel don’t give us the neutral, subjectless sentences that anyone might say, impersonally, as if language were an ideal form of transparency. Instead we get opaque texts, wounded, fragmented, obsessive signs, abandoned, delirious, solitary letters. In the end it is not language that shines through but writing—whether abstract or textual, alphabetic or architectural, deformed or infinitesimal, nominal or transitive—and, above all, its body: the graphic gesture.

If Ferrari’s abstract drawings are purely aesthetically a high point of his work, his written drawings begin to serve as a platform for objective content, for a discourse on art; on the world, with all its contradictions and nonsense; and, usually sarcastically and critically, on the powers of church and state. None of these early works are violent, or show the kind of anger and protest that would appear in his art later on, as a natural reaction to the tragedies of Argentine history, which would scar his own family directly. The period begins with works like Sin titulo (Sermón de la sangre) [Untitled (Sermon of the blood)], 1962, an abstraction based on an existing piece of writing, and can be seen as ending with La civilización occidental y cristiana (Western and Christian civilization), 1965, a sculpture fusing a crucifixion with an American bomber, an artistic gesture conceived to protest against the Vietnam war. Exhibited at Buenos Aires’s Instituto Torcuato Di Tella in 1965, the work was ultimately censored, after which Ferrari abandoned artmaking for a time. During this brief period between 1962 and 1965, Ferrari established the foundations of his entire future repertory, in abstract drawings such as the Músicas, the Escrituras deformadas, the Cartas a un general, the wire sculptures, the boxes, and the written drawings such as Cuadro escrito.

Ferrari and Schendel have never ceased to suspend their images in favor of what remains of language when it is treated like a corporeal body: a calligraphic gesture that both connects and disconnects, a binding of language, a prelinguistic, constellated configuration of weightless, arbitrary alphabets and palimpsests, of unclaimed words and letters that have fallen out of orbit. Their work, particularly that of Schendel, shows an empty, mute substratum that the signs that remain in it may once again inhabit with their full power: paper, its expanses and deserts.

This is how we may appreciate Schendel’s two greatest bodies of paper works, the Droguinhas and Trenzinho. The former—a repertory of strings and ties, of links connecting only to each other—finds complexity in the insignificant, and is an abyssal archaeology intimately concerned with writing, its mythic origins and essential rejections. Trenzinho, on the other hand, exposes its immaculate body of paper like stolen goods, a tabula rasa that once would have harbored the marks of writing but now, instead, presents its own nudity, its own void, in the form of veils and shrouds.

The simultaneous functions of indication and occultation are fundamental for both Ferrari and Schendel, who practice a kind of embodied, personalized language—a “language body,” at once the language of the body –one that points, like a finger, to the thing that is being spoken of - and the body of language. Ferrari and Schendel might have been working against Merleau-Ponty’s remark, “The marvel of language... is that it makes you forget it.” In other words, the signs in their work do not lead us to forget their physical presence. On the contrary: they confront us with their opacity and density, forcing us to remember them. Mira Schendel and León Ferrari seem to have struggled throughout their entire artistic life to restore letter to voice, voice to breath, breath to body, body to gesture, gesture to life.

1 Sol LeWitt. “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” 1967. Reprinted in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds. Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999, p. 12.

2 See Roland Barthes. “Variations sur l'écriture,” In Oeuvres Complètes. 1972–1976. Eric Marty, ed. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2002, 4:267

BIOGRAPHIES

León Ferrari and Mira Schendel are among the most significant Latin American artists of the twentieth century. Active in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s in the neighboring countries of Argentina and Brazil, they worked independently of each other, producing oeuvres that privilege language visually and as subject matter.

León Ferrari was born in Argentina in 1920. He studied Engineering in the Faculty of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences of the University of Buenos Aires. He has worked in a wide range of art forms and mediums, from sculpture, painting, drawing, and assemblage to film, collage, mail art, poetry, and sound. While living temporarily in Italy in the 1950s, he made ceramic sculptures stylistically connected to the European abstraction of the time. On returning to Argentina, he produced sculptural works of metal wires and rods before beginning a series of works on paper and, ultimately, installations, developing a practice in which organic, gestural forms appear both as abstractions and as explorations of the codes of writing. Deeply concerned with the ethical role of the artist, Ferrari later fused his avant-garde formal interests with a more political, confrontational kind of art. He is still fully active in Argentina’s contemporary-art scene and lives in Buenos Aires.

Born in Zurich in 1919, Mira Schendel (Myrrha Dagmar Dub) moved with her family to Italy while still an infant. In 1936 she enrolled at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan to study philosophy, but three years later, facing the threat of anti- Semitic persecution, she fled into exile. When World War II ended she left Europe for Brazil and began to make art, creating ceramics and then paintings. Beginning in the 1960s she produced a volume of works on paper involving self-invented techniques, manifesting her interest in transparency and the gestures of writing. In the late 1960s she made abstract, knotted sculptures of Japanese paper and other complex works that feature accumulations of signs between transparent acrylic sheets. Schendel was highly sensitive to the ethics of artmaking and she approached art as the most radical possible expression of the human condition. She continued to experiment with forms and materials until her death in São Paulo in 1988.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

León Ferrari Retrospectiva. Obras 1995-2004. Giunta, Andrea (ed). Buenos Aires: Centro Cultural Recoleta, 2004.

Souza Dias, Geraldo. Mira Schendel: do espiritual à corporeidade. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2009.

Mira Schendel: Continuum amorfo. México, D.F.: Fundación Olga y Rufino Tamayo; Monterrey, Nuevo León: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey, 2004.

León Ferrari y Mira Schendel: El alfabeto enfurecido. Pérez–Oramas, Luis (ed). Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2009.

Organized by: The Museum of Modern Art, New York

-----

Until February 25, 2010

Georges Vantongerloo. Aspiring to Infinity

Despite Vantongerloo’s regard as one of the most important artists and thinkers in the twentieth century, few exhibitions to date have been dedicated to him. Curated by Guy Brett, the Museum’s exhibition on this artist aims at exploring the fundamentals of his oeuvre, in which his re-conceptualization of space in painting and sculpture influenced artistic tendencies in early twentieth-century abstract art. The exhibition also focuses on the final period of his work after World War II, in which the artist, through a succession of radical leaps, arrived at an original and intuitive visual encapsulation of the Universe’s energy.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Sabatini Building, Floor 3

Santa Isabel, 52, Madrid

Mon-Sat 10-21 h, Sun 10-14:30 h, Tue Closed

General Admission 6, Temporary Exhibitions: 3