L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

ArtSEEN Journal (2006-2007) Anno 2 Numero 7 autunno-inverno 2007

Una lenta riconferma

Justin Randolph Thompson

Artisti Afro-Americani in Europa

Content:

Ice, Paint and Memory _ Sue Carlson

A Bunch of Flowers _ Andrew J Smaldone

A Trickling Renewal _ Justin Randolph Thompson

Form, Memory, and the Particular: The politics of monumental aesthetics _ Daniel

White

Randomly Walking Salesmen: Computing in the Depths of the Microcosm _ Sanjeev Naguleswaran

The Remains of Tomorrow _ Elena Bajo

Microcosm _ Gordana Bezanov

Con la partecipazione di Jason Mena

Sculpture Projects Münster

G. Bezanov, S. Miranda P., A.J Smaldone

n. 6 estate 2007

Francis Alÿs

Andrew Smaldone

n. 5 primavera 2007

I ♥ communism

Denis Isaia e Paolo Plotegher

n. 4 inverno 2007

Il “Moving Locker Show” – La mostra negli armadietti

Marco Chiandetti e Matt Rodda

n. 3 autunno 2006

Un pizzico di glamour

Thomas Wirsing e Sabine Wolf

n. 2 estate 2006

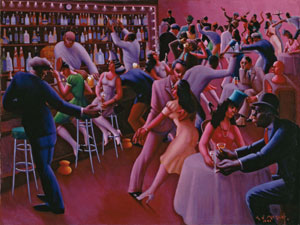

Nightlife, 1943

Oil on canvas 91.4 x 121.3 cm (36 x 47 3/4 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago

Restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Marshall Field, Jack and Sandra Guthman, Ben W. Heineman

Courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago

Courtesy ArtSEEN journal

------------english test below

L'Europa ha assistito, per più di un secolo, alla presenza di artisti,

scrittori e intrattenitori Afro-Americani e, in quell'arco di tempo,

ha osservato l'impegno di questi intellettuali nel collocare loro e la

loro arte in un più vasto ambito globale al di fuori dei già

disponibili stereotipi. Il punto di vista di coloro che si trovano

fuori dal proprio paese di provenienza spesso dà origine a cambiamenti

nell'auto-definizione di costoro e, contemporaneamente,

nell'interpretazione, da parte dei paesi ospitanti, delle altre

culture. Questo si verifica specialmente quando un gruppo oppresso

diventa in grado di oltrepassare quelle barriere culturali che giocano

un ruolo consistente nel definire classificazioni di tipo razziale. È

mia opinione che la comprensione, in Europa, dell'esperienza

Afro-Americana sia ancora pesantemente radicata a blocchi stereotipici

che a mala pena rasentano la superficie di un'enorme entità che

acquista dinamicamente nuovi strati e si ridefinisce costantemente.

Gli artisti spesso sono un indice per analizzare il cuore di una

cultura. Per questo ho intenzione di utilizzare un dialogo fra gli

Afro-Americani e l'Europa, in particolare un confronto tra due epoche

contrastanti, per sottolinearne i cambiamenti e delinearne le

somiglianze in riguardo alle rappresentazioni di razza emergenti dagli

artisti Afro-Americani fuori dagli Stati Uniti. Il contenuto raccolto

in quest'articolo è vario e affronta da una parte una corrente, negli

anni '20 e '30, di artisti Afro-Americani che hanno portato la loro

arte in Europa per studiare e rifinire le proprie tecniche e,

dall'altra un gruppo, dei nostri tempi, che opera principalmente negli

Stati Uniti e la cui arte espatria in esposizioni che mostrano

l'unicità dell'esperienza Afro-Americana e le sue trasformazioni.

Questo confronto mette in luce il cambiamento di opinione per quanto

riguarda le rappresentazioni razziali nell'arte creata da

Afro-Americani e la definizione dei diversi fattori coinvolti in

queste rappresentazioni.

Le interazioni dirette e i ritratti ad opera dei mass-media giocano

ruoli importanti nell'evoluzione della comprensione di come l'arte

Afro-Americana venga vista all'estero e, contemporaneamente, su come

l'importanza della razza cambi a seconda del cambiamento di

prospettiva. Parlare in senso olistico delle definizioni razziali

degli Afro-Americani è praticamente impossibile e la varietà di

definizioni sono spesso utilizzate dai soggetti in causa e altrettante

volte vengono forzate da agenti esterni. Diventa un'impresa il cercare

quanto di queste definizioni è determinato da fattori interni e quanto

da esterni. È indubitabile che l'interazione tra diversi gruppi

culturali crei degli ibridi che spesso vengono adottati come aspetti

nuovi ed originali di entrambe le culture. Per quanto riguarda l'arte,

anche il ruolo del patronato e quello del "Mercato dell'Arte" giocano

ruoli indistinguibili nei riguardi dei soggetti e negli stili

rappresentati. Movimenti come Harlem Renaissance e AfriCobra hanno

invocato un cambiamento, nell'arte Afro-Americana, diretto verso una

rappresentazione positiva della propria gente e dell'immaginario

Pan-Africano. Trattando questioni di razza, gli Afro-Americani vengono

spesso collegati all'Africa.

Quest'associazione ha assunto livelli ancora più complessi, data la

distanza fisica e il poco contatto diretto, che ha dato luogo alla

creazione di miti e leggende radicati in un contesto prettamente

americano e intrecciati con consistenti dosi di nostalgia fomentata da

un orgoglio crescente. Gli ibridi che questa relazione ha generato

sono infiniti e, dato il loro rapporto a distanza con il proprio

patrimonio d'origine, non ci sarebbe via d'uscita a provare a

discernerne la "purezza". Questa particolare unione tra radici

effettive e inventate ha creato le basi per un'arte esclusivamente

americana nata dal patchwork di diversi elementi culturali che parlano

di contrasti; il dar voce alla bellezza e all'atrocità, alla libertà e

all'oppressione, al lusso estremo e all'amara indigenza rappresentano

esempi perfetti di ciò che anima il cuore dell'identità Americana. Il

crescente interesse nell'ascoltare storie di gruppi oppressi, ha

permesso di farne emergere molti aspetti meno palesi. L'opera di

svariati artisti Afro-Americani è stata dedicata alla ricerca di nuovi

dialoghi al di fuori della propria patria e al comunicare, fuori dagli

Stati Uniti, i cambiamenti della realtà. Tuttavia, la visibilità e

l'interpretazione dell'arte Afro-Americana rimane, tuttora, lenta

fuori dagli USA e dunque la comprensione degli Afro-Americani tende

pesantemente verso le rappresentazioni contaminate della cultura pop.

Poco più di ottanta anni fa, l'Europa era un punto di riferimento per

molti artisti e intrattenitori Afro-Americani alla ricerca di un

rifugio da un paese che solo tre decadi dopo sarebbe arrivato a quello

che diventerà noto come il Civil Rights Movement. L'Europa era vista

come un luogo diverso, spesso socialmente più accogliente, lungi dalle

troppo consuete ingiustizie sociali e situato sull'altra sponda di

quelle stesse acque che avevano originariamente trapiantato i loro

antenati nel "Nuovo Mondo". L'opportunità di viaggiare fuori gli Stati

Uniti aiutò a sollevare molti intellettuali oltre i limiti imposti da

una nazione ancora ferita da una guerra civile e la promessa di nuove

esperienze, nuove occasioni, interazioni culturali diverse e tutte le

altre novità sono state sfruttate il più possibile da coloro che ne

hanno avuto la possibilità.

Molti hanno cercato di calcare le orme del ristretto gruppo di

artisti, tra cui Henry Ossawa Tanner, Edmonia Wildfire Lewis e Eugene

Warburg,che sono stati riconosciuti internazionalmente in seguito ai

loro anni di studio in Europa. Successivamente all'abolizione della

schiavitù molte delle idee, che imponevano di pensare agli

Afro-Americani come una "specie" destinata naturalmente alla

schiavitù, vennero messe in discussione. L'arte veniva considerata un

piedistallo illuminato e gli Afro-Americani che ne hanno preso parte

hanno scosso le radici di questi stereotipi. Gli artisti, grazie al

potere oppositivo rappresentato dalla scelta della loro professione,

viaggiando fuori dagli Stati Uniti detenevano una duplice valenza dato

il loro riconoscimento sotto una luce internazionale. Attraversando

l'Oceano, gli artisti si sono trovati circondati da un mondo che

sembrava avere la propria colonna portante radicata migliaia di anni

prima, un mondo dove la razza non veniva vista con gli stessi occhi, e

soprattutto, un luogo che non possedeva lo stesso complesso razziale.

Il dialogo europeo sulla razza era senz'altro storicamente diverso,

inoltre, i legami coloniali e la presenza di altri gruppi della

Diaspora Africana hanno creato un ambiente privo di molte delle

costanti presenti, salvo rare eccezioni, negli Stati Uniti. Con

questo, il pregiudizio razziale esisteva anche in Europa ma il

contesto artefice di questo pregiudizio era significativamente

diverso. Il periodo di cui stiamo trattando è precedente al boom che

fece dell'arte americana la figura dominante che è oggi, era ancora

l'Europa il luogo dove avvenivano la maggior parte delle innovazioni.

Inoltre, era il luogo ove il canone artistico occidentale dei maestri

del passato, così come veniva appreso in America, trovava la sua

dimora.

Molti artisti arrivarono in Europa per studiare e perfezionare la loro

tecnica circondandosi dei maestri locali. Nonostante questo nuovo

contesto fosse duramente in contrasto con l'esperienza Afro-Americana,

questi artisti e intrattenitori continuarono a sviluppare le loro

particolarità da un nuovo punto di vista esterno rispetto al loro

mondo formativo. Si evolse, così, un'arte che, sempre più, manifestava

il suo legame di sangue con l'Africa e, contemporaneamente,

rappresentava un Afro-Americano più globalmente inserito.

Parallelamente a questo periodo europeo, in America aveva luogo una

rinascita per la cultura Afro-Americana e insieme a questa,

l'affermazione dell'importanza di questa specificità dell'arte

americana. Molti artisti vennero spinti valutare la loro opera alla

luce del crescente interesse nella "New Negro Art". Spesso gli studi

condotti in Inghilterra, Italia, Francia, Belgio e Germania erano

corredati da uno stretto contatto tra le comunità di espatriati; vi

era, inoltre, un forte interesse, supportato da pubblicazioni come The

New York Herald Tribune e The Crisis, per l'attualità e le questioni

aventi luogo in America. In quegli anni,per la prima volta nella

storia, vi erano molti fondi a disposizione degli artisti

Afro-Americani e questo portò a vari episodi di successi a livello

internazionale sotto forma di mostre come quelle della Harmon

Foundation, cataloghi e recensioni. Molti degli artisti protagonisti

rimarranno espatriati a vita. Il fatto che molti sovvenzionatori di

premi e borse di studio fossero bianchi, è un aspetto che ha

certamente influito sulle tematiche e lo stile proposti dagli artisti

durante il loro soggiorno europeo. La mancanza di interesse, da parte

di coloro che elargivano i fondi, verso le sperimentazioni, trova

riscontro nell'approccio, solitamente tradizionale, dei vincitori dei

premi. Gli artisti Afro-Americani erano spesso spinti a creare opere

rappresentanti la loro cultura anche per rendere più probabile

l'assegnazione della commissione da parte dei mecenati, di colore e

non, spesso attratti da immagini rappresentanti la dignità delle

persone di colore. Ironicamente, in diverse occasioni, le immagini

rappresentate possedevano una nuance di stereotipi e caricature comuni

nelle raffigurazioni americane di soggetti Afro-Americani e nelle

raffigurazioni europee di Africani.

Dati i suoi i rapporti coloniali con l'Africa, l'Europa offriva,

inoltre, nuovi approfondimenti sulle origini africane, sotto forma di

collezioni museali quali il Musée de l'Homme e Expo coloniali, come

quella parigina del 1931. Per quanto l'onestà delle rappresentazioni

presenti all'Expo fosse contaminata, consistente fu il richiamo

suscitato dall'ingegnoso artigianato e dalle tradizioni africane. Chi,

in particolare, ne ebbe giovamento e ispirazione, furono molti artisti

Afro-Americani che mai prima di allora erano venuti in contatto

diretto con il popolo e le tradizioni dalle quali discendevano. Questi

artisti usavano ritrovarsi in cafés con espatriati provenienti dalle

Antille, dall'Africa occidentale e con altri gruppi della Diaspora

Africana. Queste nuova comunità, per quanto poco strettamente

connessa, creò una nuova opportunità per gli Afro-Americani: quella di

collocarsi in un contesto culturale più ampio. Questi artisti ed

intrattenitori, in questo nuovo contesto, lottavano contro il

contrasto nato dal tentativo di identificarsi con gli altri gruppi e

l'accettazione da parte di questi. Il nuovo e precario equilibrio

stabilitosi, ebbe un forte impatto sia nello sviluppo artistico che

nella propria identificazione razziale. Questa visione ingrandita

entrò a far parte delle opere di molti artisti e si manifestò

attraverso immagini di maschere e tessuti africani come si vede dalle

nature morte Fétiche et fleurs dipinte da Palmer Hayden, da titoli

come Divinitè négre di Augusta Savage e dai motivi dipinti come nello

sfondo storicamente corretto di A Fantasy Etiopia di Albert Alexander

Smith, dove il pittore esprime la radicata connessione con una storia

che precede notevolmente quella degli ambienti europei nei quali

questi artisti si trovavano al momento. Molti musicisti di questo

periodo si esibirono ed ebbero un successo senza precedenti in Europa;

gli artisti contemporanei a questi musicisti, invece, riscuotevano

maggior popolarità, sia per esposizioni che per vendite, negli Stati

Uniti. Spesso poveri e sempre dediti alla propria crescita artistica,

questi artisti venivano sovente nutriti spiritualmente attraverso

nuove prospettive e innumerevoli nuovi riferimenti che ispirarono le

loro opere. La ricerca di finanziamenti provenienti dagli Stati Uniti

e il tentativo di vendere opere era costante e indispensabile per

sostentare lo sviluppo degli artisti Afro-Americani oltremare.

Inoltre, il ritorno in patria, per questi artisti, era spesso accolto

con un più ampio consenso verso la loro arte.

Le opere create in quegli anni da Afro-Americani in Europa, sia che si

tratti di quadri che di sculture, sono sempre rimaste in contatto con

temi e allusioni connesse all'esperienza Afro-Americana. Questo tipo

di immaginario si vedeva realizzato spesso dall'incrocio tra nuove

idee di raffigurazione positiva degli Afro-Americani e altre che

rimanevano strettamente legate a rappresentazioni popolari di questo

gruppo. La complessità di questa contrapposizione affianca una

questione più generale, quella riguardante l'arte e il mecenatismo e

come il bisogno di essere accettato possa talvolta contaminare la

migliore delle intenzioni. Tutto ciò, accompagnato in gran parte

dalla dipendenza dai mecenati per cibo, materiali e quant'altro

occorresse all'estero, creava situazioni incredibilmente difficili da

valutare a qualsiasi livello. L'ammissione ad esporre in gallerie e la

caccia alle borse premio è sempre stata una componente delicata nella

creazione artistica, dato che gli ideali degli artisti e la loro

libertà d'espressione vedono i propri principi radicati nella

comunicazione e nell'esplorazione personale, mentre, l'importanza di

un supporto economico per continuare il proprio lavoro, risulta essere

assolutamente fondamentale.

Con il risveglio dalla Grande Depressione, seguito dall'arrivo della

Seconda Guerra Mondiale e il successivo emergere del Civil Rights

Movement, molte delle opportunità di espatrio per gli Afro-Americani

arrivarono all'estinzione a causa della mancanza di fondi, del

cambiamento dell'immagine degli Stati Uniti nel mondo e della

necessità di aiuti per l'emancipazione sociale che questo periodo

portò con sè. Molte fondazioni filantropiche, come la Rosenwald Fund

e altre che finanziavano sovente questi viaggi, prosciugarono, in

questo periodo, le loro risorse. Molti artisti iniziarono ad usare il

loro lavoro come mezzo per aiutare la lotta per la parità di diritti e

come denuncia contro pregiudizi e disuguaglianze. La mistura composta

da queste opere pungenti e da quelle che sottolineavano aspetti meno

noti dell'esperienza Afro-Americana diventerà la struttura portante di

ciò che oggi compone la maggior parte dell'arte Afro-Americana.

Richiami a brandelli del Civil Rights Movement, a nozioni sulla

schiavitù, all'identità culturale, al rapporto con la cultura

occidentale e all'immagine pop degli Afro-Americani; questi sono gli

elementi in ballo in un'arte ancora intrecciata con altri gruppi della

Diaspora Africana. La complessità che accomuna la storia dei

discendenti Africani è il filo che li lega insieme. Un legame fra

Africani e Afro-Americani che, attraverso tradizioni, storie,

argomenti e credi politici, orgoglio e dubbio, animosità e amore,

diventano un linguaggio comune capace di oltrepassare molte barriere

culturali. L'identità Americana, nella sua frammentarietà e nel suo

intreccio, costituita da elementi nati dallo scambio culturale, trova

una sua rappresentazione, oggi acclamata, nell'arte Afro-Americana.

Negli ultimi cinque anni, l'Europa ha iniziato a rinnovare il suo

interesse verso l'arte visiva Afro-Americana. Oggi è raro trovare

biennali, fiere e esposizioni museali che non includono artisti

Afro-Americani. Dato lo status dell'arte contemporanea nelle grandi

città americane, le motivazioni per viaggiare all'estero sono

cambiate, tuttavia qualcosa è rimasto simile. Gli artisti

Afro-Americani che viaggiano in Europa oggi, sono alla ricerca di

crescita spirituale e ispirazione piuttosto che di obiettivi

economici. L'Europa offre ancora senso di libertà e, il desiderio da

parte degli artisti, di essere visti in un contesto più globale, è

ancora comune. La libertà d'espressione da parte degli artisti

Afro-Americani, non è più una questione centrale in America e il

riconoscimento dell'importanza della cultura Afro-Americana si sta

diffondendo sia nell'immaginario popolare che in un'infinità di

livelli della quotidiana interazione americana. Con la crescente

tendenza dell'arte contemporanea a ricercare popolazioni mal

rappresentate in tutti gli angoli del mondo, l'importanza di un'arte

socialmente e politicamente coinvolta affiora in un dialogo

internazionale. L'ingiustizia e i conflitti presentati dai media

quotidianamente, hanno permesso una comprensione della

contemporaneità, alla luce degli errori del passato, più critica. Gli

artisti Afro-Americani sono stati riconosciuti fino al punto di

arrivare a creare un interesse mondiale verso la complessità

socio-politica della loro espressione e di aprire un dialogo che fa

luce sul "melting pot" che caratterizza gli Stati Uniti.

Nel settembre del 2006, la Zacheta National Gallery di Varsavia, in

Polonia, ha inaugurato la mostra Black Alphabet-conTEXTS of

contemporary African-American Art. Questa mostra collettiva, che

comprendeva trentacinque artisti, è stata la prima mostra europea mai

dedicata specificamente all'arte Afro-Americana contemporanea. La

presentazione di questi artisti e l'entusiasmo della critica hanno

testimoniato a favore della capacità di queste opere di oltrepassare

il contesto che ha condotto alla loro realizzazione e di ispirare un

pubblico diverso; contemporaneamente, ha sottolineato l'importanza

della voce Afro-Americana in un setting globale. La Biennale di

Venezia ha, da tempo, rappresentato un piedistallo dal quale gli

Afro-Americani hanno guadagnato ampia visibilità in Europa.

Nell'edizione del 2003, intitolata Sogni e Conflitti: la dittatura

dello spettatore curata da Francesco Bonami, artisti come Laylah Ali,

Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker e Ellen Gallagher hanno esposto le

loro opere nel padiglione italiano. Il padiglione del Regno Unito è

stato dedicato al vincitore del premio Turner, Chris Ofili, un artista

di origine nigeriana che lavora a Londra e che spesso viene incluso in

mostre di artisti Afro-Americani. Inoltre, il padiglione degli Stati

Uniti (forse il più intrigante in assoluto) ha ospitato l'istallazione

site specific di Fred Wilson che investigava la presenza africana

nella storia di Venezia. Kara Walker, nello stesso anno, ha esposto

un'istallazione presso il Museo dell'Arte del XXI Secolo di Roma. Nel

2006 una bi-personale di Leonardo Drew e Nari Ward intitolata Existing

Everywhere è stata presentata al Palazzo delle Papesse di Siena. Ward

aveva precedentemente esposto in Italia in una mostra personale,

Attractive Nuisance, alla Galleria Civica d'Arte a Torino nel 2001.

Nell'ambito cinematografico, l'artista Kevin Jerome Everson,

recentemente vincitore del Rome Prize dell'Accademia Americana e

assiduo partecipante del Sundance Film Festival, porta da tempo in

Europa le proprie pellicole. Nel 2005 ha proiettato Names and Numbers:

Films by Kevin Everson alla Whitechapel Gallery di Londra. L'anno dopo

ha partecipato a diversi eventi e festival fra i quali il Film

Festival Internazionale di Rotterdam, il Film Festival Internazionale

di Berlino, il Festival International Du Documentaire De Marseille e

la Mostra Internazionale Del Nuovo Cinema a Pescara. Nel 2007 le sue

pellicole Cinnamon e According To sono state presentate a IndieLisboa

a Lisbona.

A luglio del 2007 è stato pubblicato, dalla rivista XL de La

Repubblica,un articolo sull'arte di Kehinde Wiley. Il fatto che questo

giovane artista Afro-Americano sia stato presentato in un articolo di

una rivista dedicata alla street culture italiana, è un'affermazione

significativa riguardo il ruolo che la cultura Afro-Americana gioca in

Italia. Non è una coincidenza che le immagini dipinte da Wiley siano

facilmente identificabili con le immagini pop che MTV e le riviste di

musica presentano, dal momento che questo è l'unico scorcio

dell'attuale cultura Afro-Americana ad arrivare in Italia.

Nello stesso mese, sulla rivista D La Repubblica delle Donne,è uscito

un articolo intitolato L'Arte è Nera. In copertina Kara Walker e,

nell'articolo, immagini di David Hammonds, Lorna Simpson, Laylah Ali e

Chris Ofili offrivano una panoramica sulle tendenze attuali nell'arte

Afro-Americana e l'idea di definizione del sé in rapporto alla razza.

L'artista Yinka Shonibare (un altro artista non americano che viene

spesso incluso nelle esposizioni di Afro-Americani), che vive e lavora

a Londra, espone attualmente (fino al 4 novembre 2007) in una mostra

personale intitolata Scratch the Surface presso la National Gallery di

Londra. Questa mostra è dedicata al bicentenario dell'Atto

Parlamentare che abolì la tratta di schiavi transatlantica. Kara

Walker ha recentemente terminato una sua mostra retrospettiva presso

il Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris e Glenn Ligon ha

inaugurato un'esposizione personale intitolata Some Changes al Musée

d'Art Moderne Gran-Duc Jean di Lussemburgo. Questi due artisti, più un

altro piccolo gruppo, non sono estranei nel panorama europeo, essendo

stati inclusi in numerose mostre collettive negli anni passati. Il

crescente interesse ha dato, infatti, l'opportunità a questi artisti

Afro-Americani, di far ammirare la loro arte in mostre più grandi e in

luoghi con una consistente affluenza. L'Europa detiene ancora la

reputazione di essere la destinazione per l'affinamento tecnico delle

arti. L'attuale lenta riconferma di interesse potrebbe iniziare a

costruire una nuova realtà per la Diaspora Africana e per i suoi

artisti interessati a presentare le storie taciute della Storia

Americana e mettere in luce il crescente riconoscimento, quello che

oltrepassa gli stereotipi, che gli Afro-Americani meritano a livello

internazionale.

A Trickling Renewal

Europe has witnessed the presence of African-American artists, writers

and performers for more than a century and, in that time, has watched

as these intellectuals sought to place themselves and their work in a

larger global context outside of readily assigned stereotypes. The

vantage point provided when one moves from outside of one's land of

origin often creates shifts in self-definition and, simultaneously, in

the host countries view of any given foreign cultural group. This

holds particularly true when an oppressed group is able to step out

beyond the cultural boundaries that are a factor in defining racial

classification. It is my opinion that the understanding of the

African-American experience in Europe is still heavily based in

blockish stereotypes, barely skimming the surface of an enormous

entity, which dynamically acquires new layers and constantly redefines

itself. Artists often play the role of discerning the heartbeat of any

given culture and I intend to utilize the example of the dialogue

between African-Americans and Europe in two contrasting epochs to

underline change and delineate similarities in representations of race

by African-American visual artists outside of the United States. The

information gathered here is various and speaks both of a trend in the

twenties and thirties of African-American artists who brought their

work over to Europe to study and refine technique, and a recent group

working primarily in the US whose work arrives abroad in exhibitions,

presenting the uniqueness of the African-American experience and its

changing faces. This comparison sheds light on shifting ideas in

regard to racial representations in art created by African-Americans

and to defining factors in these representations.

Direct interactions and mass-media portrayals play important roles in

the evolving understanding of how African-American work is viewed

abroad as well as how the importance of race changes in relation to

different perspectives. Speaking holistically of African-American

racial definitions is nearly impossible and the variation of

definitions are as often self-employed as forced by external aspects.

A difficult feat arises when it comes to determining how much these

definitions are made up of internal factors, and how much of outside

factors. Doubtlessly, the interaction of different cultural groups

creates hybrids that are often adopted as new and original features of

both cultures. In regard of art, the role of patronage and the "Art

Market" also play important roles in the subjects and styles

represented. Movements such as the Harlem Renaissance, AfriCobra and

others called for a shift in African-American art towards a positive

depiction of the people and Pan-African imagery. African-Americans are

often viewed for their relation to Africa in terms of race. This view

has grown more and more complex as the physical distance and little

direct contact has created myths and legends that have rooted

themselves in a truly American context, often skewing them with

immeasurable amounts of nostalgia backed by an ever-growing pride. The

hybrids created by such a relationship are countless and there would

be no scope in trying to discern the "purity" of any of the thoughts

taken from this long-distance relationship of heritage. This

particular unity of actual and newly invented roots has become the

basis for a truly American art created by a patchwork of various

cultural references that speak of contrasts; voicing the beauty and

the atrocity, the freedom and the oppression, the extreme luxury and

bitter poverty that stand as an ideal example of the heartbeat of

American identity. The growing interest in hearing the stories of this

oppressed group has permitted several of their more subtle aspects to

surface through the work of a vast variety of African-American artists

concerned with pursuing new dialogues outside their own homeland, and

communicating changing realities beyond the United States. Visibility

and interpretation of African-American art, however, still remains a

trickle outside the US and an understanding of African-Americans thus

leans heavily on the often tainted representations of popular culture.

A little over eighty years ago Europe was a point of reference for

many African-American artists and performers seeking refuge from a

country that, not until three decades later, would see the arrival of

the Civil Rights Movement. It was a place where a different and often

more welcoming social structure could be found, miles away from the

all too familiar social injustice and across the very waters that had

originally placed their ancestors in the "New World." The opportunity

to travel outside of the US helped to lift many intellectuals beyond

the limits enforced by a nation still wounded from a civil war, and

the promise of new experiences, new opportunities, a different

cultural milieu for African-Americans, and the many other novelties

were attractive for those able to take advantage. Many artists sought

to walk in the footsteps of the handful of artists, including Henry

Ossawa Tanner, Edmonia Wildfire Lewis and Eugene Warburg, who had

received international acclaim after years of study in Europe. In the

years following the abolition of slavery, the view of

African-Americans as a "species" whose natural lot was slavery, begun

to be challenged. Art was held up as a tool of enlightenment and

African-Americans who partook in its creation challenged these views

about their capabilities. The power that this choice held by artists

who went outside of the United States was twofold as they became

recognized in an international light. Upon traversing the ocean,

artists found themselves surrounded by a world that seemed to have its

backbone rooted thousands of years earlier, a world where race was not

looked upon with the same eyes, and most of all, a place that did not

share the historical racial complex. Europe's dialogue with race was

indeed historically different and colonial ties along with the

residence of a different array of the African Diaspora created an

environment that lacked many of the constants that existed, with few

exceptions, in the States. This is not to say that the reality of

racial prejudice was non-existent in Europe, but that the context that

created these prejudices was significantly different. Europe was the

site of much innovation in the period prior to the boom that made

American art the dominant figure that it is today. It was also a place

where the art historical western canon of "the great masters," as it

was taught in the US, had its home.

Many artists arrived in Europe to study and refine their technique

while surrounded by European masters. Despite the fact that these new

contexts conflicted strongly with the African-American experience,

these artists and performers continued to develop that which was so

particular to them from this new vantage point, outside their

upbringings. An art evolved that increasingly manifested its relation

to an African bloodline and that spoke of a worldlier

African-American. This period in Europe was paralleled in the US by a

renaissance of African-American culture and with this, the

confirmation of the importance of these specifically American arts.

Many artists were pushed to evaluate their work in the light of a

growing interest in a "New Negro Art." Oftentimes, study in England,

Italy, France, Belgium, and Germany was carried out with much

communication amongst ex-patriot communities, and current events and

issues in the US continued to be followed through publications like

the New York Herald Tribune and The Crisis. Various funding was

available to African-American artists for the first time in history,

and stories of success constantly carried internationally in the form

of exhibitions, like those of the Harmon Foundation, published reviews

and catalogues. Some of these artists remained ex-patriots for life.

The fact that many of the granters of these awards where white is an

aspect that undoubtedly had an effect on the subject matter and style

of the artists during their time in Europe and, the common lack of

interest in experimentation on the part of these foundations may

attest to a generally traditional approach manifested by the winners

of these awards. African-American artists were often prompted to

create work that related to their own culture and black and white

patrons' attraction to dignified images of people of color was often

followed as a means of ensuring patronage. Ironically, in a number of

instances this imagery carried nuances of the stereotypes and

caricatures often present both in American representations of

African-Americans and in European representations of Africans.

Due to the colonial relationship with Africa, Europe also offered new

insight into African origins in the form of museum collections such as

the Musée de l'Homme and Colonial expos like that of 1931 in Paris

that, however tainted in the integrity of their representations, shed

light on indigenous African traditions and crafts. These proved

inspirational to many African-Americans who had never before had

firsthand contact with the people and traditions of their ancestry.

These artists often mingled with West Indians, West Africans and other

groups of the African Diaspora in cafés. These new communities,

however loosely woven, created fresh opportunities for

African-Americans to view themselves in a larger cultural context.

These artists and performers, in this larger context, struggled with

the contrast of their own identification with these groups, and

acceptance on the part of this community. This resulted in an extreme

impact on their artistic development as well as their own

self-definition in terms of race. A broader view entered the work of

many visual artists and manifested itself in images of nightclubs

filled with black clientele like Archibald Motley Jr.'s Nightlife,

African masks and fabrics like that of the still life painting Fétiche

et fleurs by Palmer Hayden, titles that referenced Africa such as

Divinité négre by Augusta Savage, and painted patterns like the

historically correct background of Albert Alexander Smith's, A Fantasy

Ethiopia that expressed a rooted connection to a history that went

back even further than that of the European surroundings in which they

currently found themselves.

Many of the musicians of this period performed and received acclaim at

unprecedented levels in Europe, however, the visual artists that were

their contemporaries exhibited work more frequently by sending it to

the US and had mainly American buyers. Often living in poverty and

insistently dedicating time to their artistic growth, these artists

were repeatedly fed spiritually through new perspectives and endless

references that inspired new work. They continually sought American

funding and sales to foster their development overseas. The return to

the US by these artists was, nonetheless, often met with a wider

appreciation for their work.

In this period, the works created by African-Americans in Europe,

whether painting or sculpture, almost always remained in touch with

subjects and subtleties rooted in the African-American experience.

This imagery often existed somewhere between new ideas of positive

representations of African-Americans and others that were strongly

rooted in popular depictions of the group. The complexity of this

underlying state of limbo parallels a general question in regard to

art and patronage and the need for acceptance can often taint even the

best of intentions. When coupled with the dependence, in large part,

on these patrons for their survival while abroad, situations emerged

that are incredibly difficult to evaluate on any level. Admittance to

gallery exhibitions and the quest for prizes have always been part of

the delicacy of the creation of art (challenge of being an artist), as

the ideals of the artists and their freedom of expression has

principles rooted in communication and personal exploration, while the

importance of economic backing for the continuation of work is

absolutely fundamental.

In the wake of the Great Depression, the second World War then

subsequently the emergence of the Civil Rights movement, many of the

opportunities for African-Americans to leave the United States were

extinguished through a lack of funding, a changed status of the United

States in the world view and a call for solidarity to the cause of

social improvement. In this period several philanthropic foundations

such as the Rosenwald fund that often funded these artistic ventures

desiccated their assets. Many artists begun using their work to help

fight for equal rights and an art that outwardly stated prejudice and

inequality began to surface. The mixture of these biting works and

those that expressed the subtleties of the African-American experience

would prove to be the backbone for what now makes up the majority of

contemporary African-American art. References to remnants of the Civil

Rights Movement, notions of enforced slavery, cultural identity,

relation to western culture and pop representations of

African-Americans all play a role in an art that still finds itself

intermingled with other groups of the African Diaspora. The

complexity of the shared history of people of African descent is the

thread that binds it all together. A link to African and

African-American traditions, histories, subjects, and political

beliefs, the pride and self-doubt, animosity and love become a shared

language that crosses many cultural boundaries. The fragmentary and

patched-together nature of American identity, made up of an infinite

array of cultural exchange, is exemplified by this work that has

achieved much social recognition.

Over the past five years, Europe has begun to take renewed interest in

African-American visual artists and it is now rare to find biennials,

fairs, and museum exhibitions that do not include a few. Given the

status of contemporary art in the larger cities of the United States,

many of the motivations have changed for traveling abroad, but there

are also several similarities. Many African-American artists who

travel to Europe still go for a sense of spiritual growth and

inspiration rather than the pursuit of economic goals. There is still

a sense of freedom offered by Europe and the desire to be viewed in a

more global context is still common.

The freedom of expression on the part of African-American artists is

no longer a central issue in the States and the recognition of the

importance of African-American culture is widespread both in popular

imagery and on infinite other levels of everyday American interaction.

With a growing trend in contemporary art of looking to

underrepresented populations from all over the world, the importance

of socially and politically charged art has surfaced in an

international dialogue. The injustice and conflicts, that are the

media's every day, have permitted the possibility of a more critical

contemporary understanding of many of history's flaws. Enough

recognition has been given to African-American artists to create world

interest in the social and political complexity of their expression,

opening a dialogue that sheds light on the "melting pot" that the

United States is seen to be. In September of 2006, the Zacheta

National Gallery of Art in Warsaw, Poland opened the exhibition Black

Alphabet-conTEXTS of contemporary African-American Art. This group

show that included thirty-five artists was the first ever dedicated

specifically to African-American Contemporary Art in a European

setting. The presentation of these artists and the enthusiasm of the

reviews, testifies to this work's ability to step beyond the context

that conduced its creation and to inspire a diverse public, stating

simultaneously the importance of the African-American voice in a

global setting. The Venice Biennale has long been a platform where

African-Americans have achieved widespread visibility in a European

setting and in the 2003 edition Dreams and Conflicts: The Dictatorship

of the Viewer curated by Francesco Bonami, artists Laylah Ali, Kerry

James Marshall, Kara Walker and Ellen Gallagher all presented works in

the Italian Pavillion. The British Pavilion was given to Turner

prize-winner Chris Ofili, a London-based artist of Nigerian heritage

often present in shows of African-American work. The US Pavilion

(perhaps the most intriguing to date) presented the site-specific

installation of artist Fred Wilson investigating the African presence

in Venetian history. Kara Walker opened an installation at the Museo

dell'Arte del XXI Secolo in Rome the same year. In 2006, the Palazzo

delle Papesse, a contemporary art museum in Siena, presented the

two-person show Existing Everywhere, with the work of Leonardo Drew

and Nari Ward, Ward having already presented a solo show entitled

Attractive Nuisance at the Galleria Civica d'Arte in Torino in 2001.

Filmmaker Kevin Jerome Everson, recent recipient of the Rome Prize of

the American Accademy and participant in the Sundance Film Festival on

multiple occasions, has been no stranger to Europe. In 2005, he held a

solo screening of Names and Numbers: Films by Kevin Everson at

Whitechapel Gallery in London. In 2006, he had additional solo

screenings at the Rotterdam International Film Festival, the Berlin

International Film Festival, the Festival International Du

Documentaire De Marseille and the Mostra Internazionale Del Nuovo

Cinema among others. In 2007 his films, Cinnamon and According To were

screened at IndieLisboa in Lisbon.

In 2007, a feature was printed on the work of Kehinde Wiley in the

magazine XL by Repubblica in July. The presentation of this young

African-American artist in a magazine dedicated to Italian street

culture is a significant statement about the role that

African-American culture plays in Italy. It is no coincidence that the

images painted by Wiley are easily identifiable as related to the pop

images presented on MTV and in music magazines (some of Italy's few

insights into contemporary African-American culture). The same month,

an article entitled l'Arte é Nera (Art is Black), featuring Kara

Walker on the cover and images of David Hammonds, Lorna Simpson,

Laylah Ali and Chris Ofili came out in D La Reppublica delle Donne,

offering a general spread on current trends in Contemporary

African-American art and the idea of shifts in self-definition along

racial lines. London based Yinka Shonibare (another non-American

artist often exhibited with African-Americans)has his solo exhibit

Scratch the Surface, an exhibit marking the bicentenary of the Act of

Parliament to abolish the transatlantic slave trade, at the National

Gallery in London until November 4th. Ellen Gallager recently

exhibited the Tate08 Series at the Tate Liverpool from 21 April - 28

August 2007, consisting of works exploring the myth of Drexciya -

populated by a marine species descended from captive African slaves

that were thrown overboard for being sick and disruptive cargo during

the gruelling journey from Africa to America. Kerry James Marshall

exhibited his paintings and drawings at Documenta 12 in Kassel: some

were inserted site specifically amongst a historic collection of

paintings creating an unexpected dialogue with the works of European

masters. Kara Walker, whose video installation was seen at the Venice

Biennale this year, recently closed a large survey of her work that

traveled to the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Glenn

Ligon opened his solo exhibition Some Changes on October 6th at the

Musée d'Art Moderne Gran-Duc Jean in Luxembourg. These and a handful

of others are no strangers to Europe, as they have been included in a

large number of group shows in passing years. The growing interest has

provided, however, the opportunity to view larger exhibitions of these

artists in contexts that will be widely attended. Europe perseveres as

the destination for those seeking technical refinement of their art,

and because of the current trickle of interest, it may become the

setting for a community of African Diaspora artists, interested in

presenting the untold stories of the American past and present,

gaining the international recognition, beyond the stereotypes,

deserved by African-Americans.