L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

Kaleidoscope Anno 5 Numero 21 estate 2014

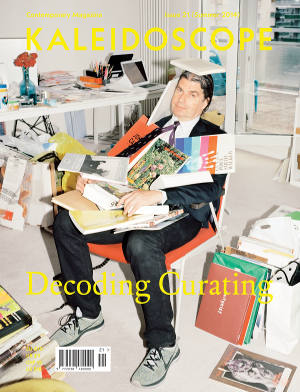

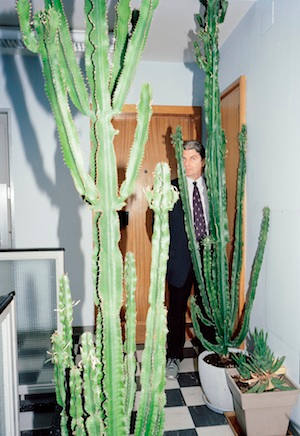

John Armleder

Andrea Bellini

Interview

a contemporary magazine

HIGHLIGHTS

Alex Gartenfeld by Nicolás Guagnini; Sarah Rifky by Laura McLean Ferris; Hanne Mugaas by Gerd Elise Mørland; Anthony Yung by Pauline Yao; Luca Lo Pinto by Ilaria Gianni

MAIN THEME – DECODING CURATING

“Curating Non-Profit” moderated by Jason Hwang; “Curating Large Scale” moderated by Chris Sharp; “Curating The Internet” moderated by Karen Archey; “Curating The Gallery” moderated by Alessio Ascari

MONO - John Armleder

Interview by Andrea Bellini; Essay by Jeanne Graff

REGULARS

Futura: Femi Adeyemi by Hans Ulrich Obrist; Pioneers: Bob Nickas by Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen; Panorama: Los Angeles by Jesi Khadivi; Producers: Stephan Trüby by Carson Chan; Vis-à-Vis: “The Art of Food” by Francesca Gavin

INSERTS: “Portraits of Society” curated by Nicholas Cullinan; Robert Mapplethorpe curated by Elad Lassry; “Coupling” curated by Piper Marshall

Torbjørn Rødland

Hanne Mugaas

n. 22 autunno -inverno 2014

Voiceover: Under the skin

Shama Khanna

n. 20 inverno 2013-2014

Yang Fudong

Davide Quadrio e Noah Cowan

n. 19 autunno 2013

Massimiliano Gioni

Francesco Manacorda

n. 18 estate 2013

John Currin

Catherine Wood

n. 17 inverno 2012-2013

Prisoner of Flesh

Michele D'Aurizio

n. 16 autunno 2012

ANDREA BELLINI: Ecart is a group of artists, an independent space and a publishing company you founded in Geneva with Patrick Lucchini and Claude Rychner in 1969. But your activity and your friendship with the Ecart founders started some years before, when you were active under the name “Bois” or “Max Bolli” group.

JOHN ARMLEDER: We were essentially a group of friends, all teenagers, and we were studying drawing with Luc Bois and doing sports with Pierre Laurent, a rowing instructor. These two teachers were our mentors.

AB: In a certain sense the Max Bolli Prize can be considered as your very first curatorial project: a trophy awarded to boats that sank or came last in official regattas.

JA: We hadn’t any manifesto, we did not share any theoretical position… We were just teenagers and we were marginal in the traditional community of Geneva’s old clubs. At the end of the year, there was always a general meeting where prizes were awarded to those who rowed for the longest, those who won regattas, etc. In a rowing club, the boat is a fetish. There is a respect for the material; there is a distinct lifestyle. We were against the hierarchy of sports success, which seemed almost similar to military success. We thus created an anti-prize, which rewarded those who did wrong, those who were breaking boats.

AB: You were developing a strong collective identity and at the same time you were working on the possibility of a group artistic practice. In French, écart means “deviation” — your art works were conceived as so many deviations from the group’s everyday life and activity. For example, if we consider the Max Bolli prize, it seems that from the very beginning you were interested in the Fluxus principle of the equivalence of life and art.

JA: Exactly. We had in mind Robert Filliou’s “permanent creation” attitude towards life.

AB: You were very young, fourteen or fifteen years old at the time — how did you learn about contemporary art and the Fluxus movement?

JA: I had a particular interest in music, and when I was very young I went to a festival in Donaueschingen, where I met John Cage who was giving a conference. During the conference I asked him something and after the speech he came and asked me what I wanted to become, and I said “a painter.” I immediately wondered why I had said that. Eight years later, while I was walking in a small pedestrian street, a person behind me called me. It was Cage. He recognized me although I had quite changed, and asked me if I had become a painter.

AB: Indeed, Cage has had a great influence on your early curatorial and artistic practice.

JA: Yes, when we founded Ecart in 1969, we organized a series of happenings, some of them based on Cage scripts. I think I had three shocks in my life. The first was when I was very young; my mother used to take us to museums when we were traveling. She would always lose me, perhaps because I was already fascinated with visual arts. I was about four years old when we visited Fra Angelico’s The Annunciation (1438– 45) in a small monastery in Florence; I cried in front of the angel’s polychrome wing. Later we also visited Giotto, which I loved, probably because for a child it looked like comics. My mother was American but always lived in Europe. She wanted us to see the promised land, because America was extraordinary in her eyes. I was eight years old when we traveled there. We visited the Museum of Modern Art in New York where she lost me again; when she found me, I was in front of Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918), mesmerized at only eight. At that moment I told her: “Look, Mom, this is modern art, this is what I want to do when I grow up.”

AB: And the third shock?

JA: … was John Cage.

AB: These really are your roots.

JA: Yes, I think so. Early on, I read Allan Kaprow’s Assemblages, Environments and Happenings (1966), in which he talks about Fluxus and the projects he did around 1957 at the Reuben Gallery in New York; it caught my attention then. I do not remember if Cage came this way or vice versa. This is also how I found myself in contact with the Fluxus people.

AB: From the very beginning, it seems, for Ecart group there was no difference between the collective practice of art and the organization of an exhibition.

JA: This is totally true. For us, everything was really coherent and organic.

AB: And talking about your curatorial activity, “Linéaments 1” in 1967 should be considered as your very first show, still as Bois.

JA: It was a call for a public participation. It was a sort of a statement: “a few young artists invite visitors to share an experience for a month.”

AB: While you were working on collective installations, you asked the audience to participate in the project. You were already developing the Ecart group’s main principles, like the disappearence of individual signatures and an active relation with the public.

JA: Yes, I remember, for example, I made a big installation, a collective sculpture, with Bois, Rychner, Tiéche and Wachmuth. It was a sort of total installation of sound, light and movement. The idea was to put spectators in the middle of an entire enviroment.

AB: The second show you organized with Ecart was the “Ecart happening festival” in 1969.

JA: We practically lived in the basement of my family’s hotel, the Richemond, for fifteen days and organized a festival. We gathered every night with people who came and we explained the next day’s theme, but we were also telling them that anyone could come with any project that we would help to implement.

AB: Then in 1972 you opened a gallery space on Rue Plantamour and you started organizing solo shows around the group members, right?

JA: At first we, Patrick Lucchini, Claude Richner and myself, mostly showed works of artists working with the Ecart group, then we started to invite other people. We had very few resources, and we quickly realized that we needed to print to disseminate our activities. But at the time, printing was complicated, expensive, and a pain to produce. We decided that the only possible way was to open a print shop ourselves. To finance this project, we printed commercially for other people, notably my family’s hotel, galleries in Geneva, restaurants, etc., which funded our own business. It has always been this way — a self-sufficient system.

AB: How did you learn about the printing process?

JA: We had a workshop outside of the gallery only in 1972, when we set up our first print shop. But we first started printing in the same basement where we had our happenings. We learned how to print on the job. There was a print shop next door where we asked for their advice, about what to do and not to do. Then we would go back to the basement and do exactly what we should not do; we thought that it would work anyway. So we developed that kind of printing very instinctively. It was attractive for the artists we exhibited, as we were not only able to produce publications, but it was also a meeting place where we spent time drinking tea. It gave artists the opportunity to suddenly create a small book, which at the time was not an easy thing to do.

AB: When you were at Rue Plantamour, you also started a sort of cooperation and mutual assistance with Adelina Von Füstenberg, who created the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in 1974.

JA: We were neighbors, and saw each other constantly. We then did several projects together. In 1977 we did a project with the Ecart performance group and some other guests like Carlos Garcia. Later, I did a solo show at the Centre d’Art Contemporain with Martin Disler and Helmut Federle.

AB: And then in 1981 you curated for the “Teu-Gum Show” for the Centre. It was a curious show, one that put togheter Jean Fautrier, Olivier Mosset, Genesis P. Orridge, Max Bolli and Walter Robinson.

JA: “Teu-gum” is the word “muguet” (lily of the valley) written backwards; muguet is the flower we give on 1 May in Switzerland. Half of the exhibition was a rerun of the “Times Square Show” curated by Walter Robinson in New York, which took place in a house in ruins. I knew Walter and I asked him if it was possible to do something similar. Almost everything had disappeared, but he offered to send me some of the works which he had kept. For the other half of the show, I then added some works by chance. For instance, Fautrier’s work was included because I bought a work at a flea market and did a kind of composition with it. I met Gustave Mescher some time before in Frankfurt — he was not making art any more, and suddenly he decided to start again.

AB: How did you feel about being artist and curator?

JA: I never really saw the difference; for me it was completely equivalent, and it still is. I never really believed in the “author.” I think that we are collective beings; our intelligence is the result of an exchange, a conversation or a negotiation, which is of course defined by the time or place in which we live. Nowadays, I think that we can escape the place where we live, much more so than when I was young.

AB: How did you choose artists for your shows?

JA: We chose artists that we were interested in and our friends. I did an exhibition with unsigned paintings that I found in resales. They were, therefore, anonymous paintings, which is funny because when people asked us who made them, we would answer that we had no idea; but they thought that we did not want to tell them. It was an issue related to the market that started to take a new form.

AB: Tell me about the show “Peintures Abstraites” (Abstract Paintings) you curated in 1986. Was this a response to the success of figurative paintings in the ’80s?

JA: It is again about opportunities. I think that in the early 1980s, there was a renewed interest in paintings on canvas. Then began “bad painting” and Neo-expressionism, notably in Italy, Germany and the US. In the 1970s, they were considered to be commodities, and so it was looked down upon somehow. But all of a sudden it came back, and as I was very good friends with painters such as Olivier Mosset and Helmut Federle, I thought that looking at painting again was great, but that abstraction was a genre of painting that we still did not look at enough. Between the three of us, Olivier, Helmut, and I, we discussed and decided on the paintings. In the end, I was more responsible for finding the paintings here and there among collectors, and I chose to invite emerging artists like Gerwald Rockenschaub, who at the time was not known at all.

AB: Can you tell me something about the two shows Marc-Olivier Wahler asked you to curate in New York and in Paris?

JA: I consider it a sort of double exhibition, first at the Swiss Institute in New York, then at the Palais de Tokyo, titled “None of the Above” (2004) and “All of the Above” (2011), respectively, which are each a line to be checked while filling out a form; it is the same idea on principles of equivalence. When Marc-Olivier asked me to do this exhibition in New York, I told myself that we could gather a few things, with the idea that it is not necessary to be able to see in order to see things. So we invited people and asked them to make miniature works, no bigger than, let’s say, a cell phone. Today, the artist list is quite impressive, because in the meantime the world has changed, and artists become famous instantly.

AB: I saw the show; I remember the space was empty and there was a little Maurizio Cattelan sculpture climbing a window.

JA: Cattelan’s piece has a long story. It was a figure of me that was originally made with my students in Braunschweig. My work there was to organize projects around the world. With the students, especially foreign students, we would gather our networks to find a space to organize an exhibition and invite artists. Then we would manage to find money, to fund the trips, and so, each time, it was self-produced. The exhibition in which the Cattelan was shown happened when I started working in Braunschweig, in a large hall on the ground floor that does not exist today. It was a little town and so we asked every garage to let us borrow some of their cars; four or five garages each lent us about ten cars for the duration of the show. I then asked students to do projects themselves or with invited artists such as Maurizio, but also Ugo Rondinone and Olivier Mosset. They each sent a project to realize; some of them came in person to make them. Maurizio asked that we make a figurine like a Garfield glued to the back of a car, but that looked like me. So, one of the students made a figurine but it did not look like me at all. He then came with Sylvie Fleury, whose aunt used to make figurines for Caran d’Arche in train station windows around Switzerland, and she made the figurine. We first showed it in Braunschweig, and as I kept it, we also showed it at the Swiss Institute where you saw it.

AB: “None of the above” was kind of funny.

JA: Because you could not see a thing and a lot of people did not get it. In 2011, Marc-Olivier asked me to do another exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo; there, I remember an opposite situation: the works are present but no one can see them because they are present. It was inspired by two things. I went to Egypt as a child and I remember the Egyptian Museum in Cairo that had a room with sarcophagi standing in front of one another, so that I could not see those in the back. But it was not easy to see those at front either; the presence of the ones behind was just as effective as the ones at front. Another experience happened in temples in Asia, where after you pass a first door, you pass by religious figurines on the sides, which filter you but that again you cannot see. When Marc-Olivier asked me to do a project, I wanted to do something in that direction. So I used this strategy and asked to build platforms on different levels for the pieces. I invited many artists and again, the exhibition’s economy was really simple: no need to look for impossible pieces, they had to choose what was available. Again, an exhibition that was built on availability rather than a list of names.

AB: The exhibition system was interesting and surprising, mostly because there did not seem to be a hierarchy between the works; they did not contradict one another.

JA: There are several possible interpretations. But the structure that I chose is the opposite of being formatted and limited — it opens all possibilities. Years before, I had hung works for Pierre Huber at Art Basel, where the entire booth was covered in mural paintings; I chose a lot of works to hang on the wall the way I wanted to, and it created a general confusion. It was interesting because the invited artists were enthusiastic to exhibit their works under these conditions, which they could have rejected in another context. I do not know why, but I am very happy when I am pushed to make a mistake.

AB: As you were saying, you have more freedom as an artist-curator than a professional curator. Artists seem to have a positive attitude towards your distinct curatorial practice.

JA: Absolutely, I may provide some opportunities that other people do not. However, some artists work as traditional curators. When I do a show, like when I make a painting, I want to forget everything I think I know — create space, rather than closing it. How does an artist have more agency to make mistakes than a professional curator? As if someone who has an art history background does something wrong, the mistake is more noticed; but if the artist does it wrong, we say it is a signature, a conscious choice.

AB: What kind of exhibition do you really not like?

JA: Well there are many things I have prejudices against, like everyone else. It happens when I see a show that I’ll consider it a bad one, but afterwards I realize that there must be something interesting that I have missed. Unfortunately I did not see Vittorio Sgarbi’s exhibition at the 2011 Venice Biennale that no one liked, so I cannot say anything bad about it.

AB: Essentially you are saying that is impossible to fail at an exhibition.

JA: Fundamentally yes, it’s impossible. I do not think one can fail in anything; a complete failure is too ambitious. Curatorial practices contribute to knowledge, provide evidences for knowledge. We say that the world is an artist and that art is life. I think that it is the same for curators; we are all curators from the start. The curator’s advantage is that he or she enters a system of knowledge that is inherently collective.