Cimento dell'armonia e dell'invenzione: or, The Drawing Machines

dal 11/11/2010 al 7/1/2011

Segnalato da

William Anastasi

Anna Barham

Emanuele Becheri

Alighiero Boetti

Ane Mette Hol

Albin Karlsson

Tim Knowles

Nick Laessing

Sol LeWitt

Giovanni Morbin

Marc Nagtzaam

Goran Petercol

Diogo Pimentao

Steve Roden

Jean Tinguely

Simone Menegoi

11/11/2010

Cimento dell'armonia e dell'invenzione: or, The Drawing Machines

Galerija Gregor Podnar, Berlin

Cimento dell'armonia e dell'invenzione (Trial of Harmony and Invention) is the title of a 1969 work by Alighiero Boetti, a series of drawings in which he traced the lines of sheets of graph paper following a different path each time. The exhibition, curated by Simone Menegoi and accompanied by a writing of Joana Neves, focuses on artists who produce drawings with machines or mechanisms following the path opened by Jean Tinguely's drawing (and painting) machines Meta-Matics, but also by self imposed rules echoing the mathematical basis of mechanical procedures, such as Alighiero Boetti himself, Sol LeWitt, William Anastasi...

curated by Simone Menegoi and accompanied by a writing of Joana Neves

Artists: William Anastasi, Anna Barham, Emanuele Becheri, Alighiero Boetti, Ane Mette Hol, Albin Karlsson, Tim Knowles, Nick Laessing, Sol LeWitt, Giovanni Morbin, Marc Nagtzaam, Goran Petercol, Diogo Pimentão, Steve Roden, Jean Tinguely.

Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione (“Trial of Harmony and Invention”) is the title of a 1969 work by Alighiero Boetti, a series of drawings in which he traced the lines of sheets of graph paper following a different path each time. A work that opposes established order (“armonia”) and the creation of something new (“invenzione”). The idea of both being at odds with each other is interesting, especially if it is applied to machinery and draughtsmanship.

The exhibition focuses on artists who produce drawings with machines or mechanisms following the path opened by Jean Tinguely’s drawing (and painting) machines Méta-Matics, but also by self imposed rules echoing the mathematical basis of mechanical procedures, such as Alighiero Boetti himself, Sol LeWitt, William Anastasi...

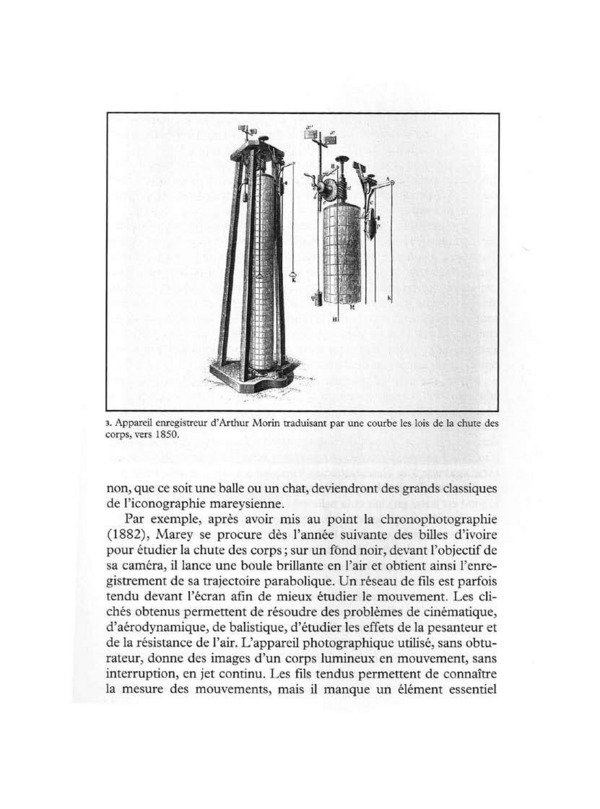

In fact, from the mid XXth century on, artistic drawing has been partly predicated upon drawing machines or mechanisms. Even in a broader and historical view, which has certainly influenced this phenomenon, drawing has been associated with mechanics in a combination of recreational and scientific uses. From the Jacquet-Droz automaton, which could draw (1772) to a machine inscribing on a sheet of paper the trajectory of a falling body, invented by Arthur Morin (1864), drawing has been both imitated and used. Etienne-Jules Marey, the inventor of chronophotography and other breathtaking experimental devices, researched the graphic translation of the body’s movements through the sphygmograph and the cardiograph, for instance, which were able to “draw” the beating of the human heart.

At first, it could seem odd that drawing, a hand-based craft par excellence, was to be included in the domain of machine-made articles. But on closer inspection, automata imitating the skills of the draughtsman upset the standards by which drawing is normally adjudged as such and announce modernity: they demonstrate the mechanic aspect of drawing without destroying its appeal. Rather, they increase it. A triangular relation between the viewer, the artist and the machine, is thus implemented. The act of creation is assumed by others, namely the machine itself, while the artist operates like one. Drawing with, or like, a machine implies an alliance of the hand, the eye, the mind, the device, the artifact, the formula and the rule.

The contemplative and epistemological role of mimesis and utility are at stake here. For from this point on, the extraction of drawn data as well as the graphic transposition of the movement of matter moulds a different and modern beauty, largely based on abstraction and, the moment drawing becomes the result of self-applied rules or exterior factors, chance-based opportunities for the unpredictable emerges. Charles Baudelaire sensed this rather early when he confessed that a fine drawing captivates us beyond what it depicts (“L’Oeuvre et la vie d’Eugène Delacroix”, 1863).

On the other hand, freed from intention and traditional ideas of quality, and fascinated by machines, the artist chooses to work programmatically. Therefore, this abstract beauty is sometimes generated by a hand carefully automated by seriality and a rigorous set of rules.

But to return to Boetti, a debate is then established as to what, exactly, one considers “harmony” and “invention” to be: would the mechanical aspect of drawing (i.e., order) be harmony? But aren’t machines, as actual mechanism or as rules and protocols, inventions? Should one consider chance itself to be the source of “invention”, as opposed to a system? Thus does this show aim to reveal the complexity and ambiguity that lurks behind such seemingly definite categories.

Cimento dell’armonia e dell’invenzione: or, The Drawing Machines will showcase historical and recent works exploring this path of contradictions between the skilled machine and the automated draughtsman, connected by the mesmerizing appeal of their abstract productions, and so much more.

Opening November 12, 2010, 6 pm - 9 pm

Galerija Gregor Podnar

Lindenstrasse 35, D-10969 Berlin

Opening hours: Tue - Sat 11 am - 6 pm

free admission