Three Exhibitions

dal 20/1/2011 al 7/5/2011

Segnalato da

The International Center of Photography

20/1/2011

Three Exhibitions

International Center of Photography ICP, New York

On diplay a solo exhibition by one of China's most innovative contemporary artists is on view. 'Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide' features a dozen large-scale photographs and three video works. In 1998, the small East Texas town of Jasper was shaken by the brutal, racially motivated killing of a forty-nine-year old African American named James Byrd Jr. This event is the subject of Alonzo Jordan's photography. 'Take Me to the Water: Photographs of River Baptisms' presents communal rites were public displays of faith, practiced by thousands of Protestants, and witnessed by entire communities.

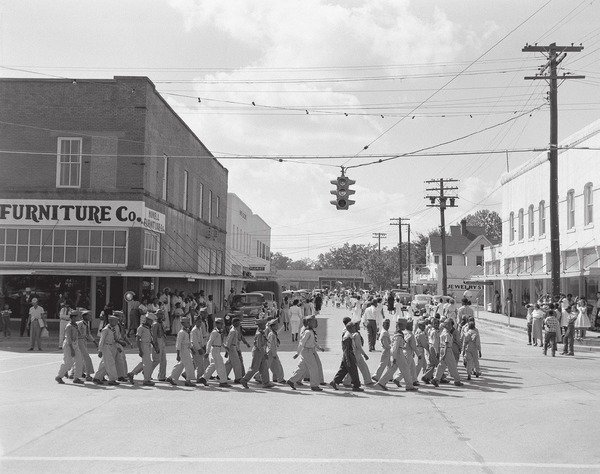

Jasper, Texas: The Community Photographs of Alonzo Jordan

In 1998, the small East Texas town of Jasper was shaken by the brutal, racially motivated killing of a forty-nine-year old

African American named James Byrd Jr. The international media coverage of that traumatic race crime did not for the most

part reveal the stark past and complicated social life of this historically segregated community. Little notice was paid, for

example, to the photographs of Alonzo Jordan (1903-1984), who had made Byrd’s high school graduation portrait, and

who had worked for more than forty years to document African Americans in Jasper and in the surrounding rural areas.

These photographs will be the subject of an exhibition, Jasper, Texas: The Community Photographs of Alonzo Jordan, on

view at the International Center of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street) from January 21 to May 8,

2011.

Like many small-town photographers, Alonzo Jordan fulfilled various roles in the community. A barber by trade, Alonzo

Jordan was also a Prince Hall Mason, a deacon in his church, an educator and a local leader, who took up photography

to fill a social need he recognized. Over the years, he chronicled the everyday world of black East Texas, especially civic

events and social rituals that were integral to the daily life of the people he served.

In addition to revealing the African American culture of Jasper during the Civil Rights era, this exhibition challenges existing

formalistic approaches to the study of vernacular photography. It considers Jordan’s distinguished career as a “community

photographer.” Guest curator Alan Govenar describes the community photographer as one who “actively documents the

world in which he lives and works, focusing on those events, ceremonies, and activities, from baptisms, weddings and

funerals to homecoming parades, graduations, and family reunions.” Govenar adds, “In communities across the nation,

photographs of this kind have been proudly displayed for decades in people’s homes, local churches, businesses, civic

buildings, and schools because they document groups and individuals who are held in high esteem. Frequently, the

photographer is not identified or credited because the emphasis is upon the family, social and professional groups, and

the recognition of the community infrastructure.”

In the introduction to the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, Alan Govenar notes, “Like other forms of folk art,

where the identities of the maker may be lost over time, Jordan’s photographs have become part of the larger public

memory of his community. The virtuosity of these images is secondary to their content. They are an expression of history

and pride, testaments not only to experiences shared and talked about, but to beliefs and values that are at the core of the

oral tradition. Together, these images form a compelling portrait of African American life in Southeast Texas.”

Concurrent with the showing of Jasper, Texas at the International Center of Photography, the Jasper County Historical

Museum and the Lone Star Community Center in Jasper are organizing an exhibition and public programs about Alonzo

Jordan’s work.

Guest Curator

The exhibition is organized by Alan Govenar, author, folklorist, photographer, and founder of Documentary Arts, Inc., a non-

profit organization that presents new perspectives on historical issues and diverse cultures. Govenar is the recipient of a

2010 Guggenheim Fellowship for his work on African American photographers in Texas and is the co-founder with Kaleta

Doolin of the Texas African American Photography Archive in Dallas.

This exhibition was made possible with support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Summerlee Foundation, and

with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

------------------------------

Take Me to the Water: Photographs of River Baptisms

Religious rituals in America are not often public spectacles. A key exception is the tradition of

river baptisms that flourished in the South and Midwest between 1880 and 1930. These outdoor

communal rites were public displays of faith, practiced by thousands of Protestants, and witnessed

by entire communities. A combination of economic depression and industrialization spurred religious

fundamentalism in rural areas, and media-savvy preachers promoted mass revivals and encouraged a

dialogue about religion in popular culture and media. Photographs of river baptisms often disseminated

as postcards, both by worshippers documenting their personal life-affirming experiences and by

tourists noting exotic practices and vanishing folk traditions will be on view at the International Center

of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street) from January 21 to May 8, 2011.

Photographs played an important role in documenting these river baptisms, especially in the early

twentieth century. For example, a panorama by the African American photographer James Calvin

Patton depicts the popular evangelical preacher Black Billy Sunday baptizing candidates in 1919

as thousands watch in Fall Creek, Indianapolis. While professional photographers were hired by the

baptismal candidates, their families, or their congregations to document the proceedings, itinerant

and amateur photographers also captured the events on film and often printed them on postcards,

which were sent or collected in albums. After the 1893 United States debut of the picture postcard at

the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, postcard fever swept the nation.

From the late 1890s to the end of the 1920s—the postcard’s golden age—two different types of

postcards were produced: real photo postcards and photomechanical postcards. Although river

baptisms were pictured in both kinds of postcards, their representations and audiences were mostly

different, as evidenced by the text on the back of the postcards that were sent. Real photo postcards

usually depict family members or friends, who are identified on the verso. Their compositions, often

frontal and symmetrical, usually try to capture as much detail as possible about the location and

onlookers; surprisingly, the focus is not always on the baptismal candidates. Stressing the communal

and social aspects of the event, these cards present the rite as an important, dignified, and solemn

occasion, a traditional and visually stunning ritual in a rapidly changing world.

Mass-produced photomechanical postcards, on the other hand, presented these religious occasions

as spectacles performed for outsiders. The tourist who purchased the postcard may have witnessed

the baptism, but probably bought the card as a souvenir, a document of a place with customs unlike

his own. Many of the mass-produced postcards depicting baptisms of African American Protestants

(often titled “Genuine Negro Baptism”) in the South were purchased by vacationing Northerners, who

expressed their amazement at these rituals in their racist messages. Often racist, these Southern

View images confirmed the stereotypical and often derisive view of the South as an “exotic” and

“primitive” place unencumbered by the technological advances of modernity. While Southerners

bore the brunt of “otherness,” Midwesterners and Westerners were not immune to Northern scorn.

Whether celebratory or ridiculing, real photo postcards and mass-produced postcards documented

and preserved a vanishing folk tradition that expressed the faith of rural believers during a time of

tremendous change in the U.S.

Take Me to the Water is drawn from a unique archive of vernacular photographs of river baptisms

donated to the International Center of Photography in 2007 by collectors Janna Rosenkranz and Jim

Linderman. The exhibition is organized by Erin Barnett, ICP Assistant Curator of Collections, and will

include vintage real photo postcards, mass-produced postcards, and a panorama. The exhibition

is accompanied by a volume Take Me to the Water, published by Dust to Digital Press in Atlanta,

Georgia; the book, which includes a CD of religious songs, was nominated for a 2009 Grammy Award.

This exhibition was made possible with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural

Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

------------------------

Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide

Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide, a solo exhibition by one of China’s most innovative contemporary artists, is on view

at the International Center of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street) from January 21 through May 8,

2011. Featuring a dozen large-scale photographs and three video works, it is the most extensive U.S. showing to date of

the work of this leading Chinese artist.

Since turning from painting to photography in the late 1990s, Beijing-based artist Wang Qingsong (pronounced “wahng

ching sahng”) has created compelling works that convey an ironic vision of 21st-century China’s encounter with global

consumer culture. Working in the manner of a motion-picture director, he conceives elaborate scenarios involving dozens

of models that are staged on film studio sets. The resulting color photographs employ knowing references to classic

Chinese artworks to throw an unexpected light on today’s China, emphasizing its new material wealth, its uninhibited

embrace of commercial values, and the social tensions arising from the massive influx of migrant workers to its cities.

Because he uses elaborate studio settings and stylized arrangements of models to make his enormous color photographs,

Wang Qingsong is sometimes likened to such contemporary artists as Gregory Crewdson. A more telling comparison,

however, might be to an earlier figure like George Grosz, whose paintings from Weimar-era Berlin are similarly filled with

needling social observation, sardonic humor, calculated awkwardness, and sometimes grotesque exaggeration. In Wang

Qingsong’s works, the artist’s deep-seated attachment to his country mixes with frequent dismay at its boom-era excesses.

China. He recoils from what he calls the “superficial splendor” of today’s Chinese nouveau-riche taste, yet he also insists,

“I like Chinese civilization. It offers an enormous space for imagination. Things take one form today, and then change to

another form tomorrow.”

Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide includes twelve of the artist’s oversized photo works—some measuring up to 21

feet in length—and three of his recent videos. In addition, a series of documentary videos on view adjacent to the exhibition

galleries takes viewers inside the artist’s studio, allowing them to follow step-by-step the creation of several of the major

works appearing in the show.

Wang Qingsong Biography

Born in 1964, Wang Qingsong grew up in the Daqing oilfields in Heilongjiang Province in northeastern China, where his

parents were employed. From a young age he set his sights on becoming an artist, although the path that he followed

was hardly an easy one. When his father died in an oilfield accident and left his family without financial support, the

15-year-old boy immediately took his father’s old place on a drilling platform and worked there for the next eight years,

while continuing to take art classes and to seek admission to China’s top art academies. Following his acceptance by the

prestigious Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Wang Qingsong trained as an oil painter, graduating in 1992. Determined to make

his way as an independent artist, he arrived in Beijing in 1993, just as Chinese contemporary art was beginning to attract

international attention.

Wang Qingsong first won recognition as a painter in the mid-1990s through his membership in the Gaudy Art group, a

movement influenced by the work of Jeff Koons and championed by China’s most influential art critic, Li Xianting. In 1997

he abandoned painting and took up photography, a medium that enabled him to quickly register and comment upon the

economic and social changes that were sweeping China. His work has now appeared in more than 20 solo exhibitions and

over 80 group exhibitions. He has exhibited internationally at such venues as the Sydney Biennale, the Gwangju Biennale,

the Havana Biennial, the Getty Museum, the Hammer Museum, the Mori Art Museum, the National Gallery of Canada, ZKM

Karlsruhe, the Moscow House of Photography, and P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center. His work was prominently featured in

the 2004 ICP exhibition Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China.

In 2001, ICP was the first museum to acquire the work of Wang Qingsong for its permanent collection. Since that time his

works are now in the collections of such institutions such as the Getty Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Mori

Art Museum, the National Art Museum of Brazil, the Hammer Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of

Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the San Diego Art Museum.

This exhibition was made possible with support from the ICP Exhibitions Committee, the E. Rhodes and Leona

B. Carpenter Foundation, Mark McCain and Caro Macdonald/Eye and I, Michelle and Mark Edmunds, Larry Warsh,

Richard Born, and with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City

Council.

Curator

Christopher Phillips has been a curator at the International Center of Photography in New York City since 2000, after serving

for 10 years as senior editor at Art in America magazine. In 2004, he and Wu Hung of the University of Chicago organized

the first major U.S. exhibition of Chinese contemporary photography, “Between Past and Future: New Photography and

Video from China.” Since that time he has curated the ICP exhibitions “Atta Kim: On-Air” (2006), and “Heavy Light: Recent

Photography and Video from Japan” (2008). He has also served as a member of the curatorial team that organized the

2003, 2006, and 2009 installments of the ICP Triennial of Contemporary Photography and Video.

ICP Library Exhibition of Books by Chinese Artists

Accompanying Wang Qingsong: When Worlds Collide, the ICP Library presents an exhibition of books by and about Chinese

contemporary artists, selected from the library’s holdings. Titled Chinese Photography in Print, it includes publications by

such artists as Ai Weiwei, Cao Fei, Hai Bo, Hong Lei, Lin Tianmiao, Liu Zheng, Miao Xiaochun, Qiu Zhijie, Rong Rong & Inri,

Wang Qingsong, and Xing Danwen.

Image: Alonzo Jordan, [Lone Star District Association parade, Jasper, Texas], October 6, 1951. © 1996 Documentary Arts, Inc.

Media Preview January 20, 2011 11:30 am–1:00 pm

RSVP: info@icp.org, 212.857.0045

International Center of Photography

1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street, New York