Industrial Times

dal 13/4/2011 al 10/9/2011

Segnalato da

13/4/2011

Industrial Times

Munchner Stadtmuseum - Sammlung Fotografie, Munich

Photographs 1845-2010. 200 original photographs from the extensive photography and graphics/paintings collections of the museum are presented for the first time ever. Starting in 1855, photographs documented the construction of railways, streets, and bridges, sometimes over the course of several years. Although by now such pictures have become popular items of the art trade, the original purpose and use of the photographs were clearly defined: to document the various construction stages.

The exhibition Industrial Era traces the development of industrial photography from its origins to the present. 200 original photographs from the extensive photography and graphics/paintings collections of the Münchner Stadtmuseum are presented for the first time ever. The exhibition is supplemented with loans from private collections in Munich and Vienna as well as a selection of the most beautiful and interesting anthologies on industrial photography from the library of the Münchner Stadtmuseum’s photography collection.

During the industrial age, the new genre of industrial photography emerged, attracting many significant European photographers who were commissioned by railroad companies, developers, engineers, or business enterprises. Starting in 1855, photographs documented the construction of railways, streets, and bridges, sometimes over the course of several years. Although by now such pictures have become popular items of the art trade, the original purpose and use of the photographs were clearly defined: to document the various construction stages of a bridge, railway track, or waterway to keep architects, engineers, and builders informed on the progress of construction since they could not always be on site. In addition, the photographs were used for product advertising at industrial and world exhibitions. It is safe to say that most likely every major traffic construction project of the 19th century was the object of a photographic campaign, even though only a few of the corresponding pictures have actually survived.

The earliest known depiction of an industrial plant in the history of photography is a daguerreotype by the French photographers Choiselat and Ratel from the year 1845 which is on display in the exhibition. Nine years later, court photographer Franz Hanfstaengl captured the creation of the spectacular glass-and-steel architecture of the Munich Glaspalast (Chrystal Palace) and the First General German Industrial Exhibition in more than 20 large-scale images. Other pictures show factories and industrial buildings that have long been replaced with contemporary architecture. An example would be Georg Böttger’s spectacular two-part panorama of a leather factory in München-Giesing from approximately 1865.

Over and over again, photographers took on the task of bearing impressive testimony on technical progress, for example by documenting the load testing of materials which was necessary for newly completed railroad bridges. In Southern Germany, Joseph Albert, Franz Hanfstaengl, and Georg Böttger were specializing in this subject. In the late 1860s, Böttger began by photographing the bridges across the Danube in Bavaria and, from 1877 onwards, the construction of the Fichtelgebirge mountain railroad. Between 1875 and 1880, Adolphe Braun from Dornach was working to capture the construction and completion of the St. Gotthard tunnel in Switzerland. Many of the pictures show that the massive soil excavations and deforesting for the construction of the bridges and roadways dramatically altered the natural environment. Mountains were pierced by tunnels; hills were leveled to make travel routes as straight as possible. Despite such massive intervention in nature, photographers usually portrayed the modern construction as merging with its natural environment and creating a romantic and idyllic atmosphere. Frequently, the iron, steel, and concrete constructions appear to be even more majestic and monumental than their natural setting which is mainly intended to serve as a backdrop for human ingenuity. Occasionally, engineers and architects posed to provide additional photographic elements, their middle-class appearance noticeably different from that of the excavation workers. What in the images appears to be a reflection of the hierarchy of the modern industrial society, in rare instances is a realistic depiction of the world of work.

Part of the large industrial projects of the 19th century was the development of rivers into waterways. The construction work on the Suez and Panama canals was documented over long periods of time by photographers who mostly remained anonymous. Smaller construction projects were photographically preserved as well, such as the reinforcement of the embankment of the Isar river in 1893. One example displayed in the exhibition is the documentation of the new regulation of the Vistula River delta created by the Gdansk photographer R. Th. Kuhn between 1889 and 1895. The high point of this extensive regulation work was breaking through a 500 meter wide coastal spit dam near Schiewenhorst on March 31, 1895. This event was captured by the photographer with a series of photographs taken in half hour intervals with a large-format wooden camera. The stark and sober composition of these landscape photographs and the preference for unspectacular motifs reflect a very modern approach that appears to be an early forerunner of the works of the photographers who – under the umbrella of “New Topographics” – have been focusing on the appearance of the modern industrial landscape since the 1970s. By comparison, the compositions of the artistic photographers around 1900 seem anachronistic. They seek to provide an atmospheric interpretation of industry by orienting themselves on landscape paintings by the Old Dutch masters and the Hague School.

After 1918, photography increasingly turned to the subject of mining and steel milling. During the heyday of industrialization in the late 1920s, Heinrich Hauser created the first series of photojournalistic articles on the Ruhr area.

The photographers of the New Objectivity movement discovered the beauty of plain factory architecture, utilitarian technical buildings, and industrial products as subjects for their direct, matter-of-fact imagery. Beginning in 1959, they served as models for Bernd and Hilla Becher’s systematic coverage of industrial buildings of the 19th and 20th century. Within the context of his broadly designed study of the Weimar Republic’s society that pursued the contemplation of “the individual” and its relationship to “the typical”, August Sander also portrayed factory workers. During the National Socialist era, the efforts to depict industrial workers without prejudice and as close to reality as possible were replaced by the pathetic conjuring of “heroes of labor”.

Industrial photographs from the post-1945 period by Erich Angenendt, Thomas Höpker, Robert Lebeck, Stefan Moses, and Alfred Trischler are cogent examples of the Federal Republic’s “economic miracle”, but also of the demise of heavy industry. In 1953, Peter Keetman photographed the assembly of the VW beetle in Wolfsburg as a coldly gleaming symbol of good fortune for the prosperous post-war republic. Like other representatives of the genre of “subjective photography” such as Otto Steinert, Toni Schneiders, or Ludwig Windstoßer, Keetman was not primarily interested in a documentary representation of the production facilities and processes but in the aesthetics of serial and structural objects, or to paraphrase the “subjectives”: in the “creation of artistic products that have value of their own.”

Located at the end of the exhibition walk-through are displays by several contemporary artists including Jürgen Nefzger and Joachim Brohm who between 1992 and 2002 documented the transformation of a derelict industrial site in northern Munich into a residential and office district.

A catalog with an extensive collection of pictures is available from the publishing house Ernst Wasmuth Verlag Tübingen and Berlin. Also included are essays by Ulrich Pohlmann und Rudolf Scheutle.

As a side event, on Thursday, April 21, 2011, the Münchner Stadtmuseum film museum will show movies by Willy Zielke on this topic, to include “The Steel Animal” (1935).

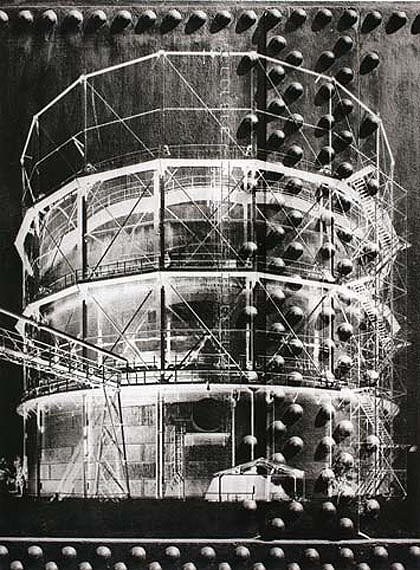

Image: Heinrich Heidersberger, Gasometer, Braunschweig, 1952, gelatin-coated paper, negative print. Münchner Stadtmuseum © Institut Heidersberger, Wolfsburg

Press contact:

Gabriele Meise Tel 089-23322994 Fax: 089 – 23325033 E-Mail: presse.stadtmuseum@muenchen.de

Opening: Thursday April 14, 2011 7pm

Münchner Stadtmuseum / Photography Collection

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1 . D-80331 Munich

Opening hours: Tues-Sun 10am-6pm

Admission

Visitor under 18 years: Entrance free

Visitor starting from 18 years: Permanent exhibitions EUR 4, reduces EUR 2, Special exhibitions EUR 6, reduces EUR 3