7/7/2011

Tiago Carneiro da Cunha and Klara Kristalova

SFMoMA, San Francisco

An exhibition that pairs figurative ceramic sculpture by two contemporary artists who are infusing the medium's unassuming form with complex political and artistic references. Kristalova's art practice uses the language of particularly idyllic and fantastic childhood reveries, yet she renders the innocent as mysterious and unsettling. Carneiro da Cunha's practice is influenced by the kitsch culture of Brazilian adventure stories and folklore, and it also encompasses violent and sexual subject matter.

Highlighting the revived medium of ceramics, SFMOMA presents New Work: Tiago Carneiro da Cunha and Klara Kristalova (July 8 through October 30, 2011), an exhibition that pairs figurative ceramic sculpture by two contemporary artists who are infusing the medium's unassuming form with complex political and artistic references.

Carneiro da Cunha lives and work in Brazil, and Kristalova is based in Sweden, but, despite very different cultural backgrounds, they work in a strikingly similar vein. Each artist draws on ceramics' association with childhood craft projects, making sculptures that conjure characters from fairy tales or comic books. The objects' distorted surfaces and rough glazing may suggest child's play, but these elements of simplicity and exuberance quickly yield to more serious concepts and darker visions. Crafting intentional imperfections into their work, Carneiro da Cunha and Kristalova subvert the assumed innocence of childlike expression and suggest history's dark potential to repeat itself if children (or adults) are told falsehoods about the simplistic nature of the world.

This latest installment of SFMOMA's ongoing New Work series is organized by Alison Gass, assistant curator of painting and sculpture, and gathers approximately 20 sculptures from public and private collections worldwide, marking both artists' first exhibition at a major U.S. museum.

"Like the best political art, these works resist didacticism, engaging instead in timeless fantasies that borrow the shared language of childhood and fundamental human psychology," says Gass. "The sculptures' universal—even fantastical—subjects, along with their intimate scale, seductive colors, and shimmering surfaces, seem equally lovely and strange. They also allow the viewer to look at them in a way that eases the contemplation of weightier issues."

With a few notable exceptions among California artists—especially in the Bay Area, where figures such as Peter Voulkos in the 1950s and Robert Arneson in the 1960s were early to embrace ceramics' potential—ceramics have remained on the sidelines of modern art, categorized primarily as the stuff of tableware and souvenir trinkets. Recent years have seen a revival of small-scale works made from ephemeral and less valuable elements, bringing ceramics fully into contemporary art practice, perhaps as part of a wider renewal of interest in fragile, imperfect, and inexpensive materials.

Klara Kristalova

Kristalova's art practice uses the language of particularly idyllic and fantastic childhood reveries (Hans Christian Andersen tales, stuffed animals, pudgy toddler bodies), yet she renders the innocent as mysterious and unsettling. In Game (2008), for instance, a young girl sits blindfolded and alone—is this truly a game or something much more sinister? The delicate bend of the figure's neck and the pale, almost-iridescent glazing seem benign, but the scene of gentle repose is broken by the drips of glaze that run from the dark edges of the blindfold.

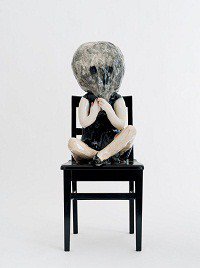

Kristalova has also made a series of sculptures of children wearing masks. These works capture the playful nature of a child's ability to make a toy from a found object, but can also feel ominous. In She's Got a Good Head (2010), for instance, the figure's hollow ghost-eyes stare out from beneath a strange balloonlike sack covering its head. The Owlchild (2009), a work that stands almost at the height of a three year old, seems at first to be a costumed figure at play. Yet Kristalova notes that it was inspired by an image of a child suffocating with a bag over its face. The figure's frozen pose resists a playful mood, instead veering into more serious territory. Fantasy likewise becomes dangerous and even physically overbearing in Kukuschnik II (2007), in which a sleeping figure is crushed under the weight of a cartoonish, mouselike creature enlarged to human scale.

Kristalova's imagery summons the contents of a little girl's ideal playroom, complete with dolls ready to be perched on the edge of a toy chest. But the distorted, ambiguous nature of her sculptures at times enters the realm of nightmares. The artist's aim, however, is not simply to shock but to reveal complexities in human nature and to examine how—for better or worse—histories are passed down through generations.

Tiago Carneiro da Cunha

Carneiro da Cunha's career began at seventeen when his comics were published in the Brazilian underground magazine Animal. While his practice is influenced by the kitsch culture of Brazilian adventure stories and folklore, it also encompasses violent and sexual subject matter. Much like the Pop-inspired artists Jeff Koons and Urs Fischer, Carneiro da Cunha experiments with a range of forms—including ceramic ashtrays, plant holders, and souvenir-like objects—that conflate high and low culture, humor and seriousness, beauty and filth.

Gargantua Rex (2009) depicts a fleshy, bloated form sinking into a bedlike base. The figure's crown and scepter mark him as a cartoonish king, head thrown back in laughter. Simultaneously grotesque and absurd, he seems the embodiment of oblivious greed and power. Lazy and inert, the reclining ruler laughs while bloody red glaze drips from his body. Here violence is combined with power, resulting in a ruler who is completely disconnected—either from his own demise or possibly from the violence surrounding or perhaps supporting his gruesome repose.

Brazil has a rich history of modernist abstraction, but Carneiro da Cunha looks further into the past. The strong colors in his work reflect Brazilian tradition, but they are also the colors of European art; renaissance painting is a particular influence. This stylistic invocation extends beyond color: Carniero da Cunha's Antropomorfismo Nietzchiano Cocando (2009), for example, echoes the composition of a reclining Venus, a renaissance staple in which a naked woman's body is stretched along a comfortable support, often in a pastoral setting. While the work approximates such a pose, it negates almost all other Venus-like elements entirely, evoking violence instead of beauty, and death rather than repose.

Klara Kristalova was born in Prague in 1967 and lives and works near Norrtälje, Sweden. She studied at the Royal University College of Fine Art, Stockholm, and has participated in numerous group and solo shows. Most recently her work was included in Luc Tuymans: A Vision of Central Europe, an exhibition curated by Tuymans for the Bruges Central City Festival 2010.

Tiago Carneiro da Cunha was born in São Paulo in 1973 and lives and works in Rio de Janeiro. He was an associate research student in the MFA program at Goldsmiths College, University of London, and has participated in many group and solo shows. He recently curated Law of the Jungle for Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York.

About SFMOMA's New Work Series

From its inception in 1987, SFMOMA's New Work series was conceived as a means to feature the most innovative expressions of contemporary art. Artists such as Matthew Barney, Marilyn Minter, and Christopher Wool were given their first solo museum exhibitions through the program, establishing the series as an important vehicle for the advancement of new art forms. Over the ensuing decade, New Work featured Glenn Ligon, Kerry James Marshall, Tatsuo Miyajima, Doris Salcedo, Luc Tuymans, Kara Walker, and Andrea Zittel, among many others. After a four-year hiatus, SFMOMA reintroduced the New Work series in 2004 and has since showcased work by Edgar Arceneaux, Phil Collins, Rachel Harrison, Wangechi Mutu, Felix Schramm, Paul Sietsema, Lucy McKenzie, Mai-Thu Perret, Ranjani Shettar, Vincent Fecteau, Mika Rottenberg, R. H. Quaytman, and Anna Parkina.

The New Work series is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and is generously supported by Collectors Forum, the founding patron of the series. Major funding is also provided by The Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation, and Robin Wright and Ian Reeves.

Media Contacts

Robyn Wise, 415.357.4172, rwise@sfmoma.org

Libby Garrison, 415.357.4177, lgarrison@sfmoma.org

Peter Denny, 415.357.4170, pdenny@sfmoma.org

Image: Klara Kristalova, She's Got a Good Head, 2010; glazed stoneware; 15 3/8 x 14 3/16 x 25 3/16 in. (38.99 x 35.99 x 64.01 cm); Mr. and Mrs. Denis Salama Collection, Paris; © Klara Kristalova; photo: Carl Henrik Tillberg, courtesy Lehmann Maupin Gallery

Openin 8 July 2011

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

151 Third Street San Francisco, CA 94103

Museum hours: Open daily (except Wednesdays): 11 a.m. to 5:45 p.m.; open late Thursdays, until 8:45 p.m. Summer hours (Memorial Day to Labor Day): Open at 10 a.m. Closed Wednesdays and the following public holidays: New Year's Day, Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, Christmas. The Museum is open the Wednesday between Christmas and New Year's Day.

Koret Visitor Education Center: Open daily (except Wednesdays): 11 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.; open late Thursdays, until 8:30 p.m. Summer hours: Open at 10 a.m.

Admission prices: adults: $18; seniors: $12; students: $11; SFMOMA members and children 12 and under: free. Admission is free the first Tuesday of each month and half-price on Thursdays after 6 p.m.