Ruben Mangasaryan

dal 13/10/2011 al 4/11/2011

Segnalato da

13/10/2011

Ruben Mangasaryan

ACCEA Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art, Yerevan

Ruben Mangasaryan's camera charted its painful progression in exhibitions such as the 1992 'Road to independence', which essentially became the thematic backbone of his entire output. Mangasaryan was naturally required to convey the viscerality and immediacy of unfolding conflicts. But one is struck by the measured, almost studied attention in the structure of his photographs.

A project of 'Ruben Mangasaryan Memorial' Foundation.

Ruben Mangasaryan was born in 1960 in a relatively liberal and modernist Yerevan—

the antithesis of everything his camera would witness two decades later. His

progressive outlook was typical of a generation that would facilitate the collapse of

the Soviet Union and engender a short-lived utopian dream for an independent

Armenia. Two earthquakes, one natural in Gyumri and the other political in Artsakh1

both of which hit the country in 1988 marked the harrowing birth of this dream.

Mangasaryan’s camera charted its painful progression in exhibitions such as the 1992

“Road to independence”, which essentially became the thematic backbone of

Mangasaryan’s entire output.

In 1985 he started working professionally as a photojournalist for agencies such as

“NovostiFoto” in Yerevan. During that time, his images of the devastation of the

Spitak earthquake wound up on the pages of the international press, which would

remain the primary forum for his work. Having spentsix years on the

Artsakhfrontline, Mangasaryan’s worldview as a photographer and aesthetic approach

came into their own.

One of his most memorable worksfrom this period is an image shot during a moment

of relative calm. It depicts a naked soldier as he prepares to dip into a natural hot

spring near one of the mountain roads in Artsakh. He carries only one thing: a

Kalashnikov slung across his shoulder. This simple scene encapsulates the originality

of Mangasaryan’s vision. The nexus of his art is not the specifics of the situation.

Instead, it is the human body that becomes the locus of the image, the device through

which Mangasaryan’s philosophy reveals itself. The metal blackness of the automatic

gun cuts across the soldier’s body with a violent force. Seen from the back, the man is

caught unawares and is devoid of any kind of insignia or protection. He is reduced to

flesh,a modern St. Sebastian whose body is likely to get pierced by bullets. The

soldier represents an elemental truth: the perpetual struggle between the body’s desire

to live and enjoy and the impulse of the mind to transcend the corporeal and achieve

spiritual grace based on some form of ideological righteousness. Unlike the St.

Sebastians of Renaissance enlightenment, Mangasaryan’s soldier does not trumpet a

virtuous triumphover death. The viewer is simply left to contemplate the tragedy of

the human condition.

This reference to an art historical and philosophical figure is not incidental. According

to his brother Tigran, Mangasaryan initially took up painting. His father,

SargisMangasաrian, was a professional painter and Tigran would become one too.

But Mangasaryan felt inadequate in this medium and turned to the camera instead,

which he was familiar with since he was seven.2His failed love affair with painting,

however,remained and would inform much of his photography’s imagery and

intellectual depth.

Working for agencies such as the BBC, Mangasaryan was naturally required to

convey the viscerality and immediacy of unfolding conflicts. But one is struck by the

measured, almost studied attention in the structure of his photographs. Almost

obsessive in his search for the perfect composition, “he would take shot after shot

before he was satisfied”3. Later in life, when he taught photography in the Caucasian

region, he would take his students to the National Gallery of Armenia and point to

examples of how meaning and subtext could be conveyed through the use of light and

composition.

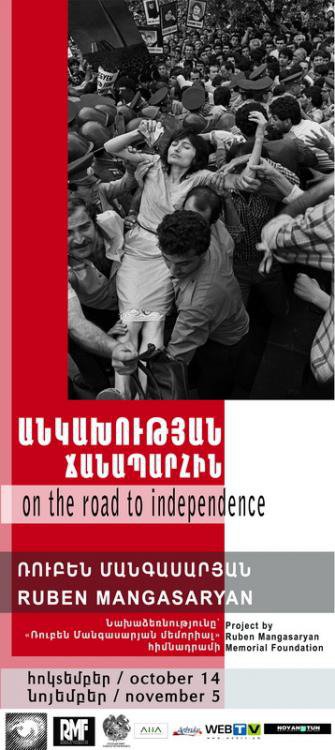

These formal traits, borrowed from painting and processed through the camera’s lens,

echo through numerous images in this exhibition. In one work, the enormous crowd

marching for independence across the “Hrazdan” bridge recalls Tintoretto’s dramatic

manipulations of perspective. In another photograph, an unconscious, grief stricken

war widow is embraced and carried by dozens of hands like a Rogiervan der Weyden

Virgin. We can also see Murillo, Velasquez and Courbet referenced in his remarkable

2004 series “Black Life”.

As Susan Sontag wrote, “all photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their

captions”.4 Perhaps that is why the photographer did not title his works. Each

photograph belongs to larger series, which Ruben frequently presented as slideshows.

But can the images speak for themselves? Roland Barthes, the great French cultural

theorist answered in the negative.5 Context, especially in war photography is

everything. In Mangasaryan’s best work, the context has open gates: these images

somehow seem to be outside time and place. “War could be photographed

anywhere... in every daily situation” he said.6 He understood that truth was a

construct with an identity, thus he sought to go beyond the limitations of ideology and

see the world from as many different viewpoints as possible. It is this profound

humanity and remarkable ability to distill meaning into visual form that ensures the

enduring power of Mangasaryan’s photographs even while the stories they

documented are long in the past.

Vigen Galstyan

1 Artsakh is the Armenian name of the Republic of Nagorno Karabagh, which broke away from

Azerbaijan in 1988 during a six year war that ended in a cease fire in 1994. The war claimed over

twenty five thousand lives, as did the 1988 earthquake in the northern part of the country.

2 Correspondence with Tigran Mangasaryan, 26.09.2011

3 Robert Kamoyan quoted in Marine Martirosyan, “Rubik was a man without limits”, interview

with painter Robert Kamoyan, 168 jam weekly online, July 18, 2009,

http://www.168.am/am/articles/19436‐pr

4 Susan Sontag, Regarding the pain of others, Picador, NY, 2003, p.6

5 See Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Vintage, London, 1993

6 Ruben Mangasaryan, Jurnalisty na voyne v Karabakhe, undated, published in the online library

of the Centre of Extreme Journalism, Moscow,

http://www.library.cjes.ru/online/?a=con&b_id=32&c_id=733

Armenian Center For Contemporary Experimental Art (“NPAK” in Armenian acronym)

1/3 Pavstos Biuzand Blvd., Yerevan, Armenia