14/2/2012

Ulla Von Brandenburg

Rosascape, Paris

For "The Nonexistent Knight" gives particular attention to the visual artifice of image duplication, of the meeting and confrontation of the real and its projection. Playing on the particular characteristics of the exhibition space - i.e., a private, domestic, intimate space, with a classical architectural style - the artist presents a series of new works here (videos, installations, drawings).

Nonexistent Knight, The A fantasy novel parodying the chivalric romance genre, written by Italo Calvino in 1959. It relays the heroic deeds of Agilulf, an imaginary paladin in Charlemagne's army who exists only as an empty suit of armour — a metal puppet held upright by his sense of duty. The coat of arms of this 'nonexistent knight' seems to be a direct product of the imagination of artist Ulla von Brandenburg: an escutcheon depicting open drapery, with another escutcheon embedded at its centre again depicting open drapery, containing yet another inescutcheon depicting yet more open drapery, and so on and so forth, infinitely — thus providing a perfect example of mise en abyme. (see 'Mirror').

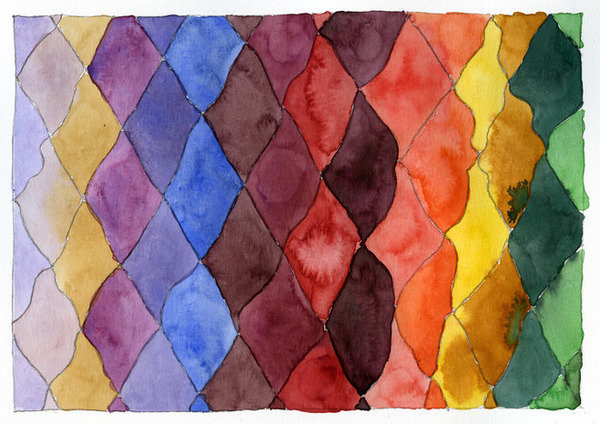

Game Chessboard, deck of cards, dice: traditional games are a frequent feature of Ulla von Brandenburg's iconography, present in her films (including The Nonexistent Knight) just as much as her drawings and installations. Certain aspects of the game — the lack of practical purpose, the rules, the entertainment dimension — connect it to one of the artist's main interests: drama. Other aspects — competition, bluffing — connect it to the jousts of social life, of which it is the sublimated form. The link connecting these three worlds — i.e., social life, games and drama — is a 2007 piece titled Karo Sieben ("Seven of Diamonds"). It is a large square platform, a few centimetres high — a kind of floor-level theatre stage covered with a patchwork of brightly coloured fabric, thus creating a singular kind of chessboard. A chessboard ideally big enough to accommodate men and women pawns.

Lozenge Out of the various motifs Ulla von Brandenburg uses, the lozenge is the artist's preferred one and the most recurrent in her work. This is perhaps due to its ambivalent character: it is a notable heraldic motif (one finds it, for instance, in the coats of arms of the princes of Monaco) yet also commonly associated with the Harlequin's costume, the valet in the Commedia dell'Arte. This character is, in turn, marked by duality: he is ingenuous yet cunning, a humble servant on the stage and a formidable demon in the old popular legends (his black, bird of prey mask is a survival of these legends). The lozenge is the servant of two masters.

Mirror Although absent from Ulla von Brandenburg's installation pieces, mirrors are quite a frequent feature of her films. They help to create their metaphysical atmosphere by creating a scene within the scene — a site from which the silent duplicates of the characters and objects behold the viewer. In The Nonexistent Knight the two male characters look at themselves in the mirror while they apply dramatic make-up to their faces. Their duplication points to the duplication of the film itself: The Nonexistent Knight is made up of two projections, seemingly identical, if not for the fact that each element that appears on the left in one projection, finds itself located on the right in the other, and vice versa. (The specular play is repeated in the chromatic motifs of the pair of draperies which complete the installation). What is fascinating is that the effect was not produced by printing a reverse copy of the film, but by shooting the action twice, the second time meticulously reversing all the actors' movements and the position of the objects in the scene. This reflection could logically give rise to a recursive principle: just as the image of the actors reflected in the mirror is amplified in the duplicated film, one might imagine an installation reflecting the two films (and the pair of draperies), duplicating them to produce four films, and yet another reflecting the latter and thus producing eight films, and so on, ad infinitum, according to the rule of mise en abyme (see Nonexistent Knight, The).

Black and White All Ulla von Brandenburg's films are shot in black and white. The artist explains this choice as a desire to give her images a timeless quality, not easily located in any particular period. But there is possibly also a reference to photography here, and to surrealist cinema where the black and white medium is used in an unsettling fashion to blur the contours of what is animate and what is not, of the living body and simulacra. (This is what Roxana Marcoci termed "the Pygmalion Complex"). And in many of her films, in juxtaposition to the animate characters, Ulla von Brandenburg stages corpses on their death bed, and ghosts.

In The Nonexistent Knight, the constitutive ambiguity of the black and white medium is brought into sharp relief via a little metalinguistic game: the female character shows her gloved hands and asks: "What colour are they?"; one of the male character answers: "It looks like dark turquoise", while the other simply answers "I cannot see, the film is in black and white".

Singspiel Until her 2009 filmic piece Singspiel, Ulla von Brandenburg's films had no soundtrack. In this film, and those which follow, sound makes an entry not as noise or dialogue but as music and singing. The characters who, judging by their stance, are most probably conversing, take turns singing stanzas of a song. The film is a reference (made explicit by the title itself) to "singspiel", a popular music drama genre where spoken dialogue alternates with song which was very widespread in German-speaking countries in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, in Ulla von Brandenburg's soundtracks, the voice (whether that of the artist herself, or someone else) is often identical even when different characters are singing, making no distinction between age or sex. Before using this expedient in her films, Ulla von Brandenburg had already been experimenting with it for several years in her playback performances. The effect it produces is to reveal each actor as "a medium temporarily possessed by the same lyrical spirit" (Chris Sharp).

Drapery The mobile fabric panel is perhaps the most emblematic and well-known feature of Ulla von Brandenburg's work. Over time it has taken on different forms which nonetheless derive from two main models: the fabric exhibition display stand and the theatre curtain. Invariably, drapery is the element which signals and delimits a space different from the space of everyday life, reserved for performance and fiction.

In the nature of things, the simulation is not limited to this space alone. In the artist's 2008 Five Folded Curtains installation piece, the visitor journeys through red theatre curtains, only to discover a space identical to the first, thus presenting both sides of the curtain as a stage. Indeed, 'the world is a stage'.

Simone Menegoi

Translated from the French by Anna Preger

Opening on Wednesday, February 15th from 6pm to 10pm

Rosascape

square Maubeuge, 3 - Paris

Opening hours

Monday – Friday, 11 AM – 6 PM

Other times by appointment

Free admission