Animal Beauty

dal 20/3/2012 al 15/7/2012

Segnalato da

Cesar

Louise Bourgeois

Jeff Koons

Leonardo Da Vinci

Alberto Giacometti

Andy Warhol

Emmanuelle Heran

20/3/2012

Animal Beauty

Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris

Through a set of major works, the exhibition looks at the relationships that artists, often great painters and sculptors, have developed with animals. It shows that there is still a close link between art and science, between our desire to know about animals and our fascination for their beauty. Paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, famous or unfamiliar... the exhibition brings together about 130 masterpieces of Western art from the Renaissance to the present day, and takes a radical new approach by choosing works in which the animal is shown on its own and for itself, without any human presence.

curated by Emmanuelle Heran

Ever since the Renaissance, artists and naturalists have observed animals closely and represented them as accurately as they could. Nevertheless, naturalism ends where the norm and morality begin: various ethical and aesthetic criteria were established which influenced the artists’ point of view. There is extraordinary variety in the ways the same animal is represented. They reveal our fascination and curiosity for a world whose diversity is far from fully explored.

Through a set of major works, the exhibition looks at the relationships that artists, often great painters and sculptors, have developed with animals. It shows that there is still a close link between art and science, between our desire to know about animals and our fascination for their beauty. Paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, famous or unfamiliar... the exhibition brings together about 130 masterpieces of Western art from the Renaissance to the present day, and takes a radical new approach by choosing works in which the animal is shown on its own and for itself, without any human presence. This marvellous menagerie, laid out in a clear design accessible to all audiences, will mingle wild and domestic beasts, the strange and the familiar.

I. Looking at Animals

Just like human beauty, animal beauty must meet specific criteria, which vary with different periods and milieus. A revolution occurred at the Renaissance: outstanding artists such as Dürer, and then the pioneers of zoology studied animals closely and described them in minute detail. This was also when the discovery of the New World revealed new animals, such as parrots and turkeys.

Repertoires were soon built up. As soon as they could study animals, painters kept a record of them in their albums, which they dipped into for motifs which had already inspired other works. They also worked on anatomical studies and tried to analyse motion, such as the movements of a galloping horse.

But man was not content to represent animal beauty; he modified it, transforming the animals themselves, with all the means that science put at his disposal. New breeds of cows, dogs and cats appear in works of art. And conversely, paintings show us breeds that have gone out of fashion.

II. Aesthetic and Moral Prejudices

We have all been influenced by Buffon and his Natural History, published shortly before the French Revolution, because of the irresistible portraits of animals it contains. But Buffon also distinguished between noble and ignoble animals. Good and beautiful were confused. His arbitrary classifications help explain our phobias for insects for example. As a result, some species were neglected by scientists and artists alike. Art these days overturns these values and artists look at animals that have long been denigrated. César’s Bat and Louise Bourgeois’s Spider are good examples.

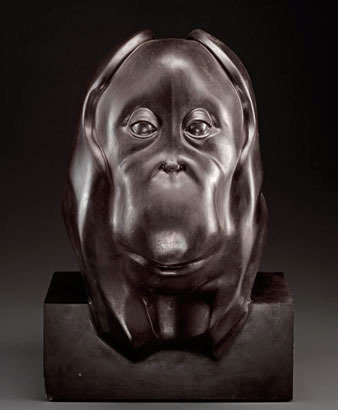

III. Monkeys and Men The publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1959 was a shock for Judeo-Christian civilisation. The naturalist developed his theory of natural selection, based on the struggle for life, and suggested that men and monkeys were cousins. Artists were keenly interested in these theories. The image of the monkey, previously ridiculed and conventional, changed radically and gave rise to disquieting portraits, like Pompon’s extraordinary Orang-utan.

IV. New Sensitivity Biblical stories tell how animals were created and later saved from destruction by Noah’s Ark. These myths tell of man’s right of life or death over his so-called “inferior brothers”. The suffering of animals was long denied and finally recognised under the impetus of writers such as Montaigne and Lafontaine. The question of whether or not animals had a soul was raised. Then empathy won the day and soon there were associations protecting animal rights (SPA in France in 1845) and a legislative arsenal (Grammont Act in France in 1850) to enforce them.

Artworks demonstrated animal sensitivity and the whole range of their irresistible expressions.

V. Otherness : Exotic Animals

In the Renaissance, exotic animals were highly sought after by the high and mighty. Kings and popes collected them in menageries to which some artists had privileged access. Their works have become precious testimonies. Visitors to the exhibition will learn of the extraordinary fate of Leo X’s rhinoceros or Charles X’s giraffe, whose journey through France from Marseille to Paris was a sensation.

In 1793, the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes sparked a craze for zoos and their popularity has never waned. France thus enabled artists to come close to animals: this was the beginning of animal painting with major figures such as Barye and Delacroix. The artist found an increasingly varied range of models in the menagerie.

Many creators now explore the relationship between men and animals and are alarmed by the threat that hangs over biodiversity. After China’s panda, and the baby seals, the polar bear has become the symbol of this threat. A powerful symbol which warns men about the future of the planet. Will a sculpture as magnificent as Pompon’s Polar Bear end up being principally a testimony to an extinct species? Will animal beauty soon be no more than a memory?

Curated by Emmanuelle Héran, heritage curator, assistant head of exhibitions at the Réunion des musées nationaux - Grand Palais

The exhibition enjoys the support of > Vétoquinol

Image: Tête d’Orang-outang, François Pompon (1855-1933), 1930, marbre noir

© RMN / A. Morin / Gallimard

Press contact: Florence Le Moing - florence.lemoing@rmngp.fr - presse@grandpalais.fr

Galeries nationales (Grand palais, Champs-Elysées)

3, avenue du Général Eisenhower 75008 Paris

Opening hours: Thursday, Saturday, noon – 8 PM Friday, noon – 9:30 PM Sunday, noon – 7 PM

Admission fee Full rate €24.00 — Concessions €12.00