Egon Schiele

dal 1/10/2012 al 5/1/2013

Segnalato da

1/10/2012

Egon Schiele

Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao

From the Albertina Museum, Vienna. In his tragically short life Schiele produced a surprisingly rich artistic legacy comprising over 2,500 works on paper and more than 330 paintings, not to mention his sketchbooks. The exhibition offers a perspective on Schiele's stylistic evolution over the course of an intensely prolific decade, which underscores the decisive role that this artist's graphic work played in shaping the history of art and consolidating his own international reputation.

Curated by Klaus Albrecht Schröder

Egon Schiele is a sweeping vision of the creative universe of one of the 20th century’s most important

artists through approximately one hundred drawings, gouaches, watercolors, and photographs on loan from

the Albertina Museum, Vienna. This institution boasts one of the world’s largest collections of historical

graphic work, including the most important compilation of works on paper by this great Austrian

Expressionist.

This show offers a unique perspective on Schiele’s stylistic evolution over the course of an intensely prolific

decade, cut short by his untimely death at the age of 28, which underscores the decisive role that this

artist’s graphic work played in shaping the history of art and consolidating his own international reputation.

Covering every stage of his career—the early pieces produced while studying at the Academy of Fine Arts,

Vienna, works heavily influenced by Gustav Klimt and Viennese Modernism, and the output of his final

years in which he made a break with naturalism, characterized by a radical use of color and new, unsettling

motifs such as explicitly erotic nudes or portraits of children—Egon Schiele is a singular, fascinating review

of the oeuvre of an artist who revolutionized art history.

In his tragically short life and barely ten years of independent artistic activity (1908–1918), Egon Schiele

produced a surprisingly rich artistic legacy comprising over 2,500 works on paper and more than 330

paintings on panel or canvas, not to mention his sketchbooks. Unlike Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), whose

drawings served as rough drafts or sketches for his paintings, Egon Schiele treated his works on paper as

independent works of art. Indeed, his works on paper show greater freedom and expressiveness than his

pictorial output.

Egon Schiele developed a highly personal, characteristic technique thanks to his decorative use of flat

surfaces and the flowing ornamental lines of the Viennese Secession style. The expressionistic body

language, gestures and mimicry seen in his work was inspired by medical photographs which documented

women suffering from hysteria, patients of Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot’s Parisian clinic at the Salpêtrière, and

by the erotic photography produced in Otto Schmidt’s studio. In his creations, Schiele returned the female

nude and other themes such as the ailing body or the pathological disintegration of personality to a new

and different limelight on the stage of art. Schiele’s work was also influenced by theosophy and Spiritism as

well as ghost photographs, which he viewed as evidence of our own mortality. For example, many of his

figures are surrounded by white halos or auras, the “light that comes out of all bodies”.

The early days and the embrace of Viennese

Despite his family’s increasingly acute financial troubles and his poor grades, Egon Schiele was admitted to

the famous Fine Arts Academy of Vienna, the most prestigious art school in the kingdom, when he was

only sixteen years old.

In the late 19th century Vienna was an elegant and aristocratic city, an economic powerhouse bursting with

vitality, and in the years leading up to World War I it experienced an unprecedented cultural boom.

Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Gustav Klimt were just some of the many world-

renowned figures who walked the streets of Vienna in those days.

Full of curiosity and fascination, the young Egon Schiele watched this cultural effervescence with intense

interest. He received a solid education at the academy, where he learned how to accurately draw the

human figure and other skills. However, he grew increasingly disenchanted with the school’s conservative

philosophy and the outdated historicist style of the “Ringstraβe era”.

Although most of the young Schiele’s early works were landscapes, he soon showed an interest in self-

portraiture, an unusual genre at the time. Even at this tender age, some of the pieces from these early

years included in the exhibition, such as Self-portrait (1906) and Self-Portrait with Headband (1909), reveal

that the artist was already starting to move away from the teachings of academicism and embracing the

modern concepts inspired by the Secession, Vienna’s answer to international modernism spearheaded by

Gustav Klimt, such as the use of flowing ornamental lines. Klimt’s influence is patent in four delicate

sketches for postcards that were never printed and are displayed as a group. In one of them, Two Men with

Halos (ca. 1909), Schiele portrays himself dressed in black.

An eloquent example of his rejection of academicism is found in one of his first and loveliest nudes from

this early period: Reclining Female Nude (1908), in which a female figure resting in a semi-prostrate pose

gives the entire work an irresistibly fluid cadence.

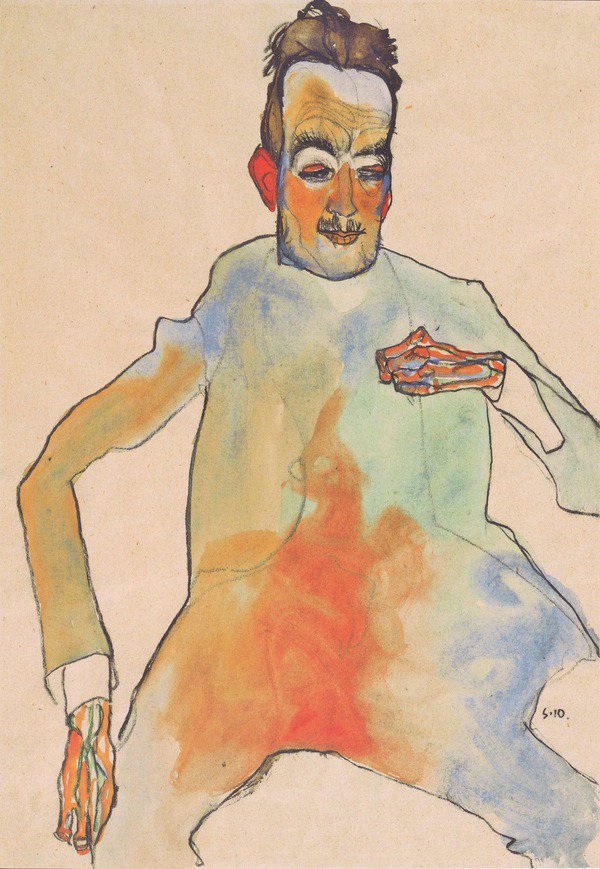

A series of portraits produced in 1909-10, including Portrait of the Painter Anton Faistauer (1909) and the

magnificent watercolor The Cellist (1910), show that the artist had already developed a unique,

unmistakable style. Although certain characteristic Art Nouveau elements are still present, these works

provide a glimpse of what would later become his signature expressionistic body language; on the one

hand, Egon Schiele defined the figure, and on the other he caused the object to omit it by adopting

unusual perspectives, striking a perfect balance between realist imitation and the purest abstraction.

First tastes of success and prison

The year 1910 marked the beginning of an intensely prolific and creative period in which he produced a

series of portraits of children characterized by their raw, natural realism—some of the most poignant pieces

in his entire oeuvre—such as Three Street Urchins (1910), Black-haired Nude Girl (1910) and Seated Nude

Girl (1910). The Austrian artist freed the erotic representation of the nude from the constraints of

caricature or pornographic photography, eliminating the historical antagonism between the beautiful and

the ugly and returning this genre to a new and different limelight on the stage of art.

In 1911 Egon Schiele and his young companion and model, Walburga “Wally” Neuzil (1894-1917), moved to

his mother’s hometown of Krumau, the modern-day Český Krumlov, a small medieval town in southern

Bohemia full of picturesque nooks, where they hoped to lead a calmer, more peaceful life than in Vienna.

Although today Krumau owes much of its fame to the urban landscapes that Schiele painted there, the

artist’s common-law living arrangements and his frequent use of children and adolescents as models flew in

the face of the conservative townspeople’s values, and he was eventually forced to leave. Egon and “Wally”

would later move back to the countryside, this time to the town of Neulengbach located 35 km west of the

capital.

Schiele was gradually making a name for himself in artistic circles, and in 1912 he participated in exhibitions

in Vienna, Budapest and Munich. However, in April of that year his life took a dramatic turn when he was

arrested and taken to the Neulengbach jail for kidnapping a minor, the daughter of a naval officer. Even

though the accusation turned out to be groundless, the artist was accused of “exhibiting erotic nudes”

because the children who visited him saw the sketches of nudes sitting around his studio; eventually he was

sentenced to 24 days in prison. One of his drawings was even burned in a symbolic act.

While serving his sentence (April 19-27 of that year), Schiele sketched a series of watercolors that reflected

the panic he felt, some of which—I Feel Not Punished but Cleansed! (Nicht gestraft, sondern gereinigt fühl

ich mich!, 20-IV-1912) and The Door into the Open (Die Tür in das Offene, 21-IV-1912)—can be seen in

this exhibition.

Success and demise

Following this unpleasant episode, the artist left Neulengbach and, after traveling to several places,

returned to Vienna for good. Over the course of 1913 and 1914, Schiele—aided once more by the critic

Arthur Roessler—took part in numerous exhibitions across Germany, in Munich, Hamburg, Breslau,

Stuttgart, Cologne, Dresden and Berlin. However, his works were also shown in Rome, Brussels and Paris,

and Egon Schiele’s prospects for an international career looked very promising.

By mid-1913 Schiele’s drawing style was characterized by irregular penciled outlines and the apparent

instability of his figures on the pictorial surface, as we can see in Female Torso with Raised Shirt (1913).

Around 1914 he began to exhibit a tendency towards schematization and geometry that was anything but

natural. One example is the splendid gouache Redemption (Erlösung, 1913), where the volume and

plasticity of the head contrasts with the flatness of the textile elements, and another is Kneeling Female

Nude with Outstretched Arms (1914) which expresses the existential uncertainty about human gender by

eliminating all facial expressions or gestures of the portrayed woman as well as all contextual references.

That same year, Schiele started working in his studio with the photographer Anton Josef Trcka and

produced a series of photographs that can be seen in this exhibition. The theatrical dramatization of the

poses struck by the artist and his typically Expressionist gestural language speak volumes of his

contribution to these images.

The outbreak of World War I (1914–1918) suddenly crushed all of Schiele’s hopes and dreams. Though

initially deemed unfit for duty, he was eventually called up in June 1915. However, thanks to the support of

friends and a few officers who admired his talent, he was never sent to the front and instead was assigned

desk jobs in Vienna and Lower Austria, where he was able to draw and even had a studio for a time. That

same year he was married in Vienna to Edith Harms, one of the daughters of a petit-bourgeois family who

lived across the street from his studio in the Austrian capital.

Edith and her sister Adele both posed regularly for Schiele. In Portrait of Edith Schiele (1915), the artist

captured the poignant, melancholy facial expression of his young bride, and in Portrait of the Artist’s

Sister-in-Law Adele Harms (1917), with stunning naturalism he portrayed Adele in an elegant dress of

black-and-white stripes, focusing his attention on the ornamentation of her figure.

The 1915 work Seated Couple, a portrayal of two lovers in which the man hangs from the woman’s arms

like a ragdoll, skillfully reflects the artist’s deep-seated conviction that human beings are essentially alone in

the world and that the chasm between men and women is unbridgeable. This existential pessimism, which

evolves into the allegory of an encounter between life and death, would remain with the artist for the rest

of his career.

In 1917 his work was featured in shows in Amsterdam, Stockholm and Copenhagen. In March 1918, during

the 49th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession, “a show conceived to exhibit the new Austrian art,” Schiele

occupied a prominent position that marked the pinnacle of his artistic and financial success: he managed to

sell many of his pictures and received commissions for several new works.

Schiele had always longed for peace and had great plans for the days after the end of the conflict; he

hoped to promote a new humanist education for the younger generation and participate in the

construction of a new, better world. Sadly, in the fall of 1918 his wife Edith came down with the Spanish flu,

which decimated Europe and claimed millions of lives, and she died on October 28 while she was six

months’ pregnant. While caring for her, Egon also caught the disease and died three days later. He was just

28 years old.

Yet even in the course of such a short-lived career, Egon Schiele managed to make a unique contribution

to the development of 20th-century art.

Historical context and educational spaces

Egon Schiele was born in Austria on June 12, 1890, the same year that Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

passed away in France. In those times Austria was not the small Alpine republic it is today but the great

central European empire of the Habsburgs, with a territory one-third larger than that of modern-day Spain.

By the late 19th century the heyday of that territory, in constant expansion since the Middle Ages, had

already come and gone, and since 1867 it had been divided into two regions with identical rights: Austria

and Hungary. Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the last respected symbol of the

unity of the “Danubian Monarchy”, had already occupied the throne for 42 years when Egon Schiele

entered the world.

In the late 19th century and the years leading up to World War I, Vienna experienced an unprecedented

cultural boom.

This show is accompanied by an educational space in both the exhibition galleries and along the third-floor

corridor that will offer visitors additional details about the artist’s life in the context of the social and

political transformation of Austria, a nation with a thirst for modernity that has produced some of the

greatest advances in the humanities (Sigmund Freud and his theories on sexuality and psychoanalysis),

sciences (medical research into mental illnesses and women’s health) and arts (formation in 1897 of the

Secessionists, which included representatives of architecture, design and visual arts).

The educational space will also reveal Schiele’s relationships with other artists and intellectuals and explain

how they influenced his creative process, such the man he considered his mentor, Gustav Klimt. Every day

the Museum will offer a nonstop screening of the documentary entitled Sex and Sensibility: The Allure of

Art Nouveau, directed by John MacLaverty in 2012 for the BBC, which sums up all of these ideas.

Catalogue

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao has published a fully illustrated catalogue to accompany this exhibition

which features reproductions of the works in the show as well as an essay by the curator and director of the

Albertina Museum, Klaus Albrecht Schröder, on the central motifs and formal principles that dominate

Egon Schiele’s work, detailed entries on each piece in the exhibition, and a complete biography of the

artist.

Image: The Cellist, 1910. Black chalk, watercolor on packing paper, 44.7 x 31.2 cm. Albertina, Vienna, inv. no. 31178

MEDIA RELATIONS

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

Dept. of Communications and Marketing

Tel.: +34 944 35 90 08

Fax: +34 94 435 90 59

media@guggenheim-bilbao.es

All information on the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao at www.guggenheim-bilbao.es (Press Room).

FOR FRANCE:

FOUCHARD FILIPPI COMMUNICATIONS

Philippe Fouchard-Filippi

Tel : 01 53 28 87 53 / 06 60 21 11 94

Email : phff@fouchardfilippi.com

Guggenheim Bilbao Museum

Galleries: 305, 306, 307

Abandoibarra Hiribidea, 2 - 48009 Bilbao, Spain

Tuesday to Sunday 10 am to 08 pm

Monday closed.

The Museum will be closed on December 25 and January 1.

On December 24 and 31 the Museum will close at 5 pm

Admission,

Adults: 8 €,

Senior: 5 €,

Groups: 7,50 €,

Students: (< 26 years) 5 €,

Children and Museum Members free