Thomas Bayrle

dal 9/2/2013 al 13/6/2013

Segnalato da

9/2/2013

Thomas Bayrle

The Artist's Institute, New York

The sixth season at The Artist's Institute is with the German artist: "he distorts the distortions, normalizes the normalizations, compresses the compressions, standardizes the standardizations, mediocritizes the mediocrities, and repeats the repetitions".

Today, we should be thinking about

the artist Thomas Bayrle (b. 1937,

Berlin).

The year is 1936. The film, Modern

Times. It begins in a factory, on an

assembly line, with Charlie Chaplin trying

to tighten bolts. It isn’t going well.

In 1958, Thomas Bayrle worked

as an apprentice in a textile factory in

Göppingen, near Stuttgart. The noise

and repetition of factory life was slowly

driving him crazy—until he started to sing

to himself. He matched his own murmur

to the rhythm of the loom, sinking into

the machine. Bayrle stopped fighting the

machines but synched his body to them,

like one clutch disk that approaches

another, enabling the gears to shift. In that

moment, he remembers hearing the rosary

from his childhood: the tender voices of

nuns, dressed in black, reciting the Ave

Maria in long strings of repetitive chants,

breathing in, breathing out.

This early experience was both

traumatic and ecstatic, but it made one

thing very clear: meditation and machines

belong together. Both are made of pure

repetition.

After studying at the Arts and Crafts

school in Offenbach, Bayrle started

making books with his friend Bernhard

Jäger, and they founded Gulliver Press in

1962. Using hot-metal typesetting, they

made small editions of concrete poetry: a

single letter goes next to other letters to

form a word, words make a sentence, a

book, and end up as an entire library. And

then back to the single letter, made of lead.

Bayrle soon began building his own

kinetic sculptures—Joseph Beuys referred

to him as “the guy with the machines.”

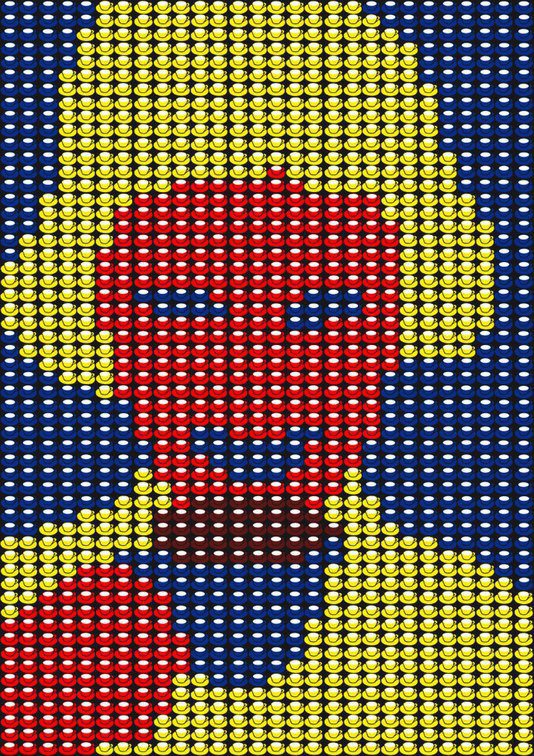

He has made prints, collages, silk-

screens, and developed what he calls

superforms, images made of many smaller

images of themselves. In the 1980s, he

began printing images on fragile latex, and

asked friends to help him distort them on

photocopy machines—each person held

a corner and pulled in different directions

as he photocopied thousands of stretched

images. These modules came together as

collages, animations, and films.

His cardboard models of roads are

warped into infinite interlocking strips.

It’s as if millions of bodies in millions

of cars were using millions of tanks of

gas to travel across millions of miles on

millions of roads built with millions of

tons of concrete.

It’s what Bayrle calls the quality of

quantity, or the process of making pure

quantity into a quality. Quality is merely

the distribution aspect of quantity, as

Vladimir Nabakov once put it.

The context matters here: 1960s

Germany lived through its so-called

economic miracle, when, a few short

years after a devastating war, everyone

was buying shiny new toasters and

washing machines. This contradiction

involved a mixture of gratitude and

skepticism. Capitalism was a savior and

a monster—fascinating and repulsive.

During that period, Bayrle read Mao

Zedong’s On the Correct Handling

of Contradictions Among the People

(1957). He saw the Chinese “permanent

revolution” as a commitment to

continuous motor activity—a form of

weaving—and liked Mao’s dialectics

between unity and struggle.

But communism still looked pretty

much like capitalism. Both talk about

giving power to the powerless, but end

up absorbing and transforming them into

statistics. They both turn cars into traffic.

Traffic. For Bayrle, the world is made

of traffic: everything is always moving

and always stuck in place at the same

time. We work, buy, use, pray, fuck, drive,

make, cook, break, choose, decide—it’s all

traffic, moving at the rate of a trillion yes’s

and a trillion no’s per second. My work is

always 50-50, he says.

Traffic doesn’t care. It is indifferent. It

doesn’t discriminate, it only accumulates.

It isn’t extraordinary or terrifying, it’s

just mediocre. Grey. Like a sticky jelly

or a thick porridge, it spreads itself over

a collective of repeated individual units

and organizes them, fixing them into a

temporary configuration. Most people hate

traffic, but there is a certain intelligence to

its stupidity—it bends, swerves, and moves

in a rhythm that no single one of its units

can control. Call it the power of crowds

(Elias Canetti) or the mass ornament

(Siegfried Kracauer), but it reveals the

tendency for mechanized repetition to take

on generative and aesthetic properties.

Grey Pop.

People say we’ve shifted from an age of

production to one of consumption. At this

point, it’s become an age of accumulation,

of all of the above. We don’t choose

between objects or ideas as much as

we accumulate them, holding on to all

options. We don’t agree or disagree, we

filibuster and save for later.

Thomas Bayrle asks what is micro

about the macro and what is macro about

the micro. His work tries to locate where

the individual stops and the ornament

begins: cells and bodies, people and icons,

threads and woven fabric, cars and traffic,

prayers and religion, image and pattern,

sex and porn. The world is constantly busy

moving one into the other, with all of the

distortions this might involve or require.

The question becomes what to do about

it. From his time as a weaver, Bayrle

knows that straightforward rebellion or

didactic critique don’t go far. Best to

swim with the current. So instead, he

sinks into the machine, stays elastic, and

tries to match its rhythm: he distorts the

distortions, normalizes the normalizations,

compresses the compressions, standardizes

the standardizations, mediocritizes the

mediocrities, and repeats the repetitions.

I want to take consistency to the point

where it becomes inconsistent.

Society is organized in refrains, with

recurring patterns we learn to recognize

and rely on. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi

describes art and poetry as an attempt to

move language so that it deploys a new

refrain. This is what Bayrle does—he

perverts mass culture’s refrains.

His perversions are laced with politics

and jest—a bit like caricature. Whereas

most caricaturists exaggerate what’s

abnormal, Bayrle builds on what’s

normal—to such an extent that it becomes

disfigured and grotesque.

Christine Mehring calls it a

comedic clash of scale, tautology, and

transformation.

Sherrie Levine once described her habit

of taking a photograph of a photograph

in terms of playing the same note on

two different pianos at the same time—

it sounds the same, but it also sounds

different. There is a vibration inside the

repetition, somewhere.

That vibration can be explosive. It can

agitate. It can be extreme. It can lubricate.

It can burn. It can force an error. It can

cause trouble. It can make bodies go soft

and go sideways. It can revitalize touch.

It can move anxiety into laughter. It can

make things change. It can stop making

sense. It can move it move it. It can

Rock’n’Roll.

A-wop-bop-a-loo-mop-a-wop-

bam-boom.

Image: Milchkaffee, 1967 Silkscreen on plastic, 200 x 145 cm Städtische Galerie, Wolfsburg

Opening Reception: February 10, 2013 - 6 - 8pm

The Artist’s Institute

163 Eldridge Street in New York City

Friday, Saturday, Sunday, 12-6pm