Macchiaioli

dal 11/9/2013 al 4/1/2014

Segnalato da

11/9/2013

Macchiaioli

Fundacion Mapfre, Madrid

Realismo impresionista en Italia. The exhibition brings together around 70 paintings from some of the most prestigious public and private Italian collections: the Galleria d'Arte Moderna del Palazzo Pitti, in Florence, Rome's Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Milan, Venice's Fondazione Musei Civici and Galleria Internazionale d'Arte Moderna di Ca'Pesaro, the municipal museum of Giovanni Fattori, in Livorno, and the Istituto Matteucci in Viareggio, among others.

In Florence, towards 1855, a group of young painters was undertaking a quest for a new kind of art. They were deeply opposed to both the academic style of painting and historic Romanticism, the contexts of their training, and were pursuing truthfulness in art, adopting outdoor painting as their preferred practice.

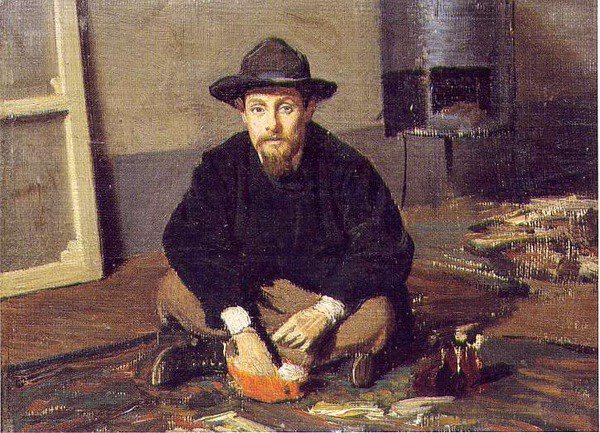

In their paintings, small in size, but grandiose in their conception, these young painters created an authentic and innovative vision of the Tuscan landscape, with stark contrasts of light and shadow achieved through the juxtaposition of blotches of color. Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, Telemaco Signorini, Giuseppe Abbati, Giovanni Boldini and Odoardo Borrani were among the main protagonists of the movement, all of them gathered around critic and patron Diego Martelli.

Known as the Macchiaioli (“blotch-makers”) – a name intended to be pejorative, alluding to the marked simplicity of their paintings – they were the instigators of one of the most brilliant chapters of the modernization of European painting, anticipating a significant number of the premises later proclaimed by the Impressionists.

This show was co-produced by FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE and the MUSÉES D’ORSAY ET DE L´ORANGERIE, in Paris, where it was recently exhibited with great success. The exhibition brings together around 70 paintings from some of the most prestigious public and private Italian collections; stand-out contributors include the Galleria d’Arte Moderna del Palazzo Pitti, in Florence, Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’ Arte Moderna, the Galleria d´Arte Moderna in Milan, Venice’s Fondazione Musei Civici and Galleria Internazionale d´Arte Moderna di Ca’Pesaro, the municipal museum of Giovanni Fattori, in Livorno, and the Istituto Matteucci in Viareggio, among others.

This is the first exhibition about the movement to take place in Spain, despite the importance and influence of the Macchiaioli on Spanish painting at the end of the 19th century.

The Caffè Michelangiolo

Discussion is the life of art. Telemaco Signorini, in the Gazzetino delle artie e del disegno [Art and Design Gazette], 1867

In the middle of the 19th century, Florence fostered intense cultural activity. During the years of the Resurgence, the social and political importance of the town grew exponentially, particularly during the years in which it was the capital of Italy. From 1852, the Caffè Michelangiolo was transformed into a meeting place for Florentine artists as much as for those from other parts of Italy, and the rest of Europe (Manet, Degas and Tissot). Situated close to the Piazza del Duomo, in the Via Larga (now Via Cavour), the café had a small private room where the group of young artists, subsequently known as the Macchiaioli, would meet.

The regulars of the Caffè Michelangiolo engaged in passionate discussions about art and politics: their commitment to an artistic renewal ran in parallel to their political ideals in favor of a new Italy. Congregated around the critic and patron Diego Martelli, they rebelled against the academic style of painting they had been taught and looked, above all, for an honest truth, without artifice, which they captured in simple landscapes, country scenes or in their portraits of the bourgeoisie. Also in discussion in the café were the innovations taking place on the Parisian art scene, thanks to those painters recently returned from their trips to Paris.

The union of the artistic and political ideals of these artists also translated into a strong bond of friendship between them. They worked together in Castiglioncelli, in the farm Diego Martelli had inherited in 1861 and shared with his painter friends, studying the rich color palettes of the Tuscan countryside; they worked together in Piagentina, painting the calm of the Italian bourgeoisie, reminiscent of the Quattrocento artists.

The set of portraits presented in this exhibition bears witness to the friendship that united these painters, but also to their need to affirm themselves as artists in their everyday attitudes, without the falseness of the Romantic portrait, painting, from nature, their small-format panels created using patches of color.

The Conquest of Outdoor Painting

Nature, considered as a reality with no other importance than that which is inherent to it, interwoven with the beauty of light and color, of truth and the variety of the elements, will reclaim the idea of seasons, feelings and the passing of time. Ferdinando Martini, L'Arte contemporanea e l'Esposizione della Nuova Società Promotrice [Contemporary Art and the Exposition of a New, Supportive Society], Florence, 1865

The Macchiaioli’s revolution found its raison-d’être in outdoor painting, which would become its main defining feature. In its proposal for a new form of art, this group of painters identified itself with the Tuscan landscapes, bathed in sunlight, with very clearly defined interplay between light and shade achieved with patches of starkly contrasting color, with great conciseness in the detail within them and created through successive scenes, in the style of the Quattrocento’s great masters.

For the first time, landscapes by Vincenzo Cabianca, Giovanni Fattori, Odoardo Borrani and Giuseppe Abbatti, whether in La Spezia, Livorno or Castiglioncello, attempted to express the feeling of a particular place, in a particular season, at a fixed time. The artists moved to different places together to paint from nature and, in this sense, their way of working bears similarities to that of the Barbizon school; nevertheless, the Macchiaioli proved to be bolder and they faced the landscape, pure and simple, full of light and color, with a freedom that was previously unheard of.

The rectangular formats in landscape orientation, like their use of wood as a preferred choice of base, must be put into the context of the Florentine predellas of the Trecento and the Quattrocento. In the same spirit, the thorough construction of their compositions gave their scenes new solemnity and grandiosity: the world of the country folk was distanced from social realism, to be cast under an elegiac regard, which found a new poetry in a life that was rural, sincere and simple.

The Macchia

The figures are almost never bigger than 15 centimeters, which is the size that a real-life scene seems to be when observed from a certain distance, that is, at that distance where the parts of the scene that made an impression on us are seen as a mass, rather than in detail; therefore, the figure seen against a white wall […] can be perceived as a dark patch on a light one. Adriano Cecioni, Scritti e ricordi [Writings and Memories], Florence, 1905

The Macchiaioli’s radical artistic experimentation was concentrated into the small panels they painted, no more than 15 centimeters high. They were little wooden boards, more often than not retrieved from different sorts of packaging, cigar boxes, for example; they served as a base upon which oil paints could be applied without primer, leaving the grain of the wood visible.

The Macchiaioli’s method favored succinctness, mass and the relief, in contrast to the descriptive thoroughness and detail of earlier Romantic paintings. Reality was observed as the juxtaposition between patches of color in stark contrast with each other, because, although light does not alter color, it radically transforms the intensity of the tone. In this way, they established a rigorous, geometric synthesis of shapes: having limited the principles of painting in light and shade, the spatial construction and organization came from the lines created between the light-colors and shadow-colors.

The aforementioned definition of composition through the use of patches, or blotches, of color caused an anonymous critic to give these painters the pejorative name of Macchiaioli (“blotch-makers”); it was a name that Signorini would adopt for the group, in 1862, thus establishing a clear parallel with the term ‘Impressionism’, which would be coined, with intended irony, by journalist Louis Leroy in 1874 and adopted by Monet and his friends.

Like the Impressionists, the Macchiaioli had a deep interest in experimenting with new approaches to color and optics. Through the use of light and color, the Impressionists built a new way of looking at the real; however, the Macchiaioli, ‘simplified’ the traditional approach, using these very same principles to eliminate the habitual scenographic perspectives, and thus revisiting the thinking of the 15th century.

The Unification of Italy

Italy, now free and united, almost in its entirety, with the admirable assistance of Divine Providence, by the accorded will of its Peoples and through the magnificent bravery of its Armies, puts its trust in your virtue and wisdom. Víctor Emmanuel II, Discurso inaugural del Parlamento de Italia [Inaugural Speech of the Italian Parliament], Turin, 18th February, 1861

During the first half of the 19th century, Italy witnessed a huge patriotic national movement. Despite rifts, this movement was united by the conviction of the value of the existence of an Italian nation, worthy of its own state. Patriotic ideals were widely diffused, engaging aristocrats and the bourgeoisie, the middle and working classes and, of course, intellectuals and artists.

The young people of the Caffè Michelangiolo were politically engaged and volunteered to fight in the Italian wars of independence and to contribute to campaigns in favor of unification. In this way, not only did they turn into veritable agents of the warlike conflicts of the Resurgence, but also, through their paintings, into exceptional chroniclers of the political situation they were living through.

At the same time as a wave of bellicose rhetoric was being unleashed, devoted to glorifying martyrdom and military sacrifice, the Macchiaioli were putting forward a disenchanted and brave view of their own experiences, and were constructing a new image of the Resurgence based on purely artistic values.

The Painting of the Personal

[...] to create a form of art in which the sincerity of the interpretation of reality and truth could return, without plagiarizing the Pre-Raphaelites, to that of our great artists of the Quattrocento, and to continue the healthy tradition – no longer with the divine sentiment of that time, but with the human sentiment of our era. Telemaco Signorini, Per Silvestro Lega. Ricordo [For Silvestro Lega. Recollection], Florence, 1896

After the most experimental period of the Macchia, which took place during the first half of the 1860s, particularly in Castiglioncello, some artists took up residence in Piagentina, a controversial sanctuary, which the Macchiaioli adopted in opposition to the way Florence was developing at the time of Haussmann. Silvestro Lega shut himself off in the Batelli family’s home; Telemaco Signorini, upon his return from Paris, moved to a house near to Lega’s, as did Odorado Borrani.

During this period, the genre of portraiture was particularly beloved and popular among the Macchiaioli. A fundamental maxim was to surpass the conventions of the pose and setting of the Biedermeyer period in favor of a natural-looking model and an everyday feeling to the setting they found themselves in. In fact, the natural ease of the pose represented a serious contradiction of the ‘distinction’ of the purist canon, and this was a difference that these young painters worked hard to highlight.

In Piagentina, the artists were working on personal portraits of the peaceful and elegant intellectual middle classes, who, for the Macchiaioli, would be the dominant class of the new, united nation of Italy. Sealed within their intimate scenes of women was a confidence in a serene and well-structured world.

There was clear evidence of a need to revisit the tradition of the Florentine Quattrocento and make it their own, with the capacity to convert it into a solid base upon which they could build a national artistic style. The artists found ways to work which would allow them to unite this tradition with a new style of painting that put high stakes on the principles of the use of light.

Mariano Fortuny

[...] just to allow myself the luxury of painting for myself: this is what real painting is all about. Fortuny in a letter to Davillier, 9th October, 1874

At the same time as the Macchiaioli’s ventures, a commercial style of painting was being developed in an extraordinary way in Europe, with pleasant scenes set in times gone by, in small formats, with a refined and affected style, delighting collectors and dealers alike. Mariano Fortuny was one of the greatest representatives of this genre; disdained by the Macchiaioli, he was the target of a significant debate about the concept of truthfulness in art.

Nevertheless, during the most intense years of this debate, Fortuny grew sick of having to adapt his work as dictated by commercial painting and, little by little, his oeuvre moved towards outdoor painting, with a huge sense of freedom, coming closer – although mostly opposed to them in attitude – to stylistic presuppositions very similar to those developed by the Macchiaioli. Although there was no close connection between them, Fortuny and the Macchiaioli were drinking from the same artistic fountain as Naples-born Dominico Morelly, and found very similar solutions to his stylistic quest.

The small collection of Mariano Fortuny’s paintings shown in this exhibition aims to testify to the proximity between their respective offerings. Through noticeably rectangular formats, and on diminutive, natural bases, the painter from Reus demonstrated his fascination with the principles of light, constructing his landscapes on successive planes, with strong contrasts between light and shadow. The profound influence that this very personal episode in Fortuny’s work had on the subsequent generation of Spanish painters, among whom Pinazo and Sorolla stand out, is the link that connects the Macchiaioli’s painting with the best of Spanish painting at the end of the 19th century.

Image: Giovanni Boldini, Ritratto Diego Martelli, c. 1865. Firenze, Galleria d'arte moderna di Palazzo Pitti

Fundacion Mapfre

Paseo de Recoletos 23 - Madrid - 28004

Mondays from 2 pm to 8 pm.

Tuesday through Saturday from 10 am to 8 pm.

Sundays and holidays from 12 noon to 7 pm