The Avant-Gardes at War

dal 6/11/2013 al 22/2/2014

Segnalato da

6/11/2013

The Avant-Gardes at War

Bundeskunsthalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn

The exhibition is the first to investigate and present in depth the fate of modern art in the context of the First World War by presenting some 300 works from around 60 artists. Works by Arp, Baldessarri, Carra', Duchamp, Klee, Kokoschka, Malevich, Picasso, Schiele and many others.

The first and second decade of the 20th century witnessed an unprecedented

explosion of artistic movements all over Europe. The outbreak of the First World

War in 1914 brought much of this creative ferment to an abrupt end. At a time

when politics sought to stoke enmity between Germany and France, artists

exchanged ideas and collaborated across national borders with unprecedented

intensity. Paris was the centre of the new art, yet it found its most enthusiastic

early advocates in Germany.

The exhibition is the first to investigate and present in depth the fate of modern

art in the context of the First World War by presenting some 300 works from

around 60 artists.

Before 1914: The first section of the exhibition investigates the way different

artists related to the war. Even before 1914, artists in Germany and Austria – for

example Alfred Kubin, Ludwig Meidner and Oskar Kokoschka – had given visual

expression to disturbing apocalyptic thoughts. Other artists like Ernst Barlach,

Franz von Stuck, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Luigi Russolo or Gino Severini

indulged in manifold images of fighting.

From the Studio to the Battlefield: The collapse of the newly-built edifice of

international artistic exchange and collaboration dealt Modernism a decisive and

tragic blow. Many artists left their studios for the battlefields, some – among

them Umberto Boccioni, Franz Marc, August Macke, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and

Albert Weisgerber – never returned. International artists’ groups disbanded

because the former guests had become ‘enemy aliens’ and had to leave the host

country: Kandinsky went back to Russia, Kahnweiler was forced to leave France,

Chagall could not return to Paris, the Delaunays fled to neutral Spain etc. In 1915

Marcel Duchamp, who had gone to New York, wrote ‘Paris is like a deserted

mansion. Her lights are out. The friends are all away at the front. Or else they

have already been killed.’

‘Avant-garde in uniform’: While artists such as Franz Marc, André Mare and

Dunoyer de Segonzac used avant-garde forms in the design of military

camouflage, Kazimir Malevich in Russia, Raoul Dufy in France, Max Liebermann

in Germany produced patriotic pictures.

Severe Traumatisation: The third section of the exhibition looks at the severe

traumatisation of many artists within months of the outbreak of the war. The

existential experience of suffering and destruction led painters and graphic

artists such as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix or Egon Schiele

– even Paul Klee – to poignant new themes and novel techniques. It was during

the first year of the war that Franz Marc collected the motifs for a future pictorial

world. Félix Vallotton, Frans Masereel and Willy Jaeckel created graphic series.Prospects for the 20th century 1915–1918: In 1916, with the war still raging

across Europe, a group of émigré artists in neutral Switzerland founded the

Cabaret Voltaire, the birthplace of Dada, that international protest movement

against absolutely everything. At that time Duchamp was already working on his

Large Glass. In 1917 Guillaume Apollinaire called for an esprit nouveau as the

epitome of culture shaking off the fetters of the old and coined the term

surrealism. Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich approached the complete

abstraction. Thus it was during the war – outside its direct sphere of influence –

that major perspectives for 20th century art were developed.

The exhibition is under the patronage of the German Federal President Joachim

Gauck.

Introduction

For the international avantgarde, the year 1914 represented a fundamental

historical caesura.

The outbreak of the war saw the collapse of the close international relationships

between the artists. Whether as volunteers or conscripts, they were suddenly in

uniform. Many Franco-German friendships became armed political enmities.

August Macke was killed in action in September 1914, Franz Marc in March

1916. Marcel Duchamp, who fled to New York, wrote that Paris, the capital of the

art world, ‘was an abandoned house’. ‘The lights have gone out. The friends are

gone – to the front. Or they have already been killed.’

The question behind this exhibition was: what effect did the idea of war and from

August 1914 the reality of war have at first on the work of avantgarde artists? The

exhibits include both pro-war and anti-war works, works created under the

pressure of the war, and works created in spite of it.

The exhibition starts with two paintings by Lovis Corinth with a symbolic

content: a bellicose Self-portrait in Armour dating from 1914, and, from 1918, the

Pieces of Armour in the Studio, bereft of all but artistic purpose.

The Avantgarde Prior to 1914

A Golden Age

The years immediately prior to the outbreak of the First World War were the

golden age of the international avantgarde. In France, Picasso and Braque

together developed a pictorial language of facetted forms: Cubism. In 1912 they

added items from the everyday world, thus re-uniting artwork and reality.

Unlike these artists, who because of the their German dealers, were regarded in

France as boches (derogatory term for ‘Germans’) and thus as politically suspect,

Gleizes and Metzinger painted Cubist works regarded as typically French. For

Delaunay and Léger, the Cubist imagery was no longer an end in itself, but a

means of coming to terms with the theme of the large modern city.

The avantgarde tone in Germany was set by the Munich-based artist-group

known as Der Blaue Reiter, whose members included Wassily Kandinsky, Franz

Marc, Gabriele Münter and Alexej von Jawlensky. In their works, unlike those by

the Cubists, the expressivity of colours played a major role. At about the same

time in Prague, František Kupka arrived at a similar pictorial conclusion to

Kandinsky – namely abstraction.

Premonitions

Even before 1914, the optimism of the avantgarde was alloyed with dark

forebodings, the sense of standing at a turning point in history. The Austrian

artist Alfred Kubin understood in masterly fashion how to give expression tothese existential fears. His pictorial world is permeated by fantastically combined

incarnations of the menacing and demonic.

With his apocalyptic landscapes, Ludwig Meidner added an unmistakable note

to the eschatological pessimism of the day. In the works he painted before the

outbreak of the war, the world is coming to a noisy end: a preview of things to

come.

Jakob Steinhardt used the motif of the contemporary city to illustrate his view of

the world. He presents it as a place not of gleaming modernity, but of dislocation

and decline.

Encircled by Enemies

Feinde ringsum (Encircled by Enemies) the title of a sculpture by Franz von Stuck,

is taken from a slogan uttered by Kaiser Wilhelm II in August 1914, and so this is

also the title of this room, whose main theme is different meanings of the word

‘struggle’.

Ernst Barlach’s Rächer (The Avenger) together with the lithograph Der heilige Krieg

(The Holy War), whose motif is the same, calls on Germans to honour their

higher duty to the fatherland. Emil Nolde’s paintings, by contrast, display an

altogether ambivalent relationship to the war.

In the work of Roberto Baldessari and Gino Severini, we see a flaring up of the

patriotic pathos of the Italian Futurists. The motif of the street decorated with

flags, often to be seen in French painting of the time, and here illustrated by a

work of Raoul Dufy, testifies at first to an – if anything – innocent patriotism, but

as preparations for war got under way, takes on political significance.

Kandinsky’s perspective was quite different: his apocalyptic scenes express the

conviction that from the ruins of the old world, a new spiritual order would

emerge.

1914. Into War

Patriotic, popular

Instead of standing at their easels in the studio, artists now served as soldiers at

the front – or else on the ‘home front’.

Thus at the outbreak of the war, the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky is said to have

endlessly and publicly declaimed ‘bloodthirsty and virulently anti-German

verses’ in Moscow. Such texts were also created for propaganda sheets designed

by the Russians Kazimir Malevich and Aristarkh Lentulov in the style of the old

Russian lubok or popular print.

Vernacular images also inspired the French painter of serene landscapes Raoul

Dufy, when in 1914 he drew coloured propaganda sheets in the style of the

popular prints known as images d’Épinal.

The series of ‘artist flysheets’ that appeared from the end of August 1914 in

Berlin under the title Kriegszeit (Time of War) were entirely in the spirit of the

Kaiser’s war policy. Max Liebermann, August Gaul and Ernst Barlach all suppliednumerous contributions. In Italy, Carlo Carrà helped to fire patriotic enthusiasm

with his publication Guerrapittura (War Painting) in 1915.

Camouflage

When, during the war, Picasso saw a cannon painted in Cubist camouflage

colours, he is said to have exclaimed: ‘That’s our doing!’ When artists were

commissioned to design and implement camouflage patterns for ordnance, they

applied their formal innovations. The sketchbooks of the Cubist André Mare

bear particular witness to this.

In France Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola headed the camouflage team to

which the painters André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Roger de la Fresnaye, Jacques

Villon and André Fraye belonged. On the German side, Franz Marc was assigned

to paint camouflage. His letter, written in February 1916, gives more detailed

information.

In England artists such as Norman Wilkinson and Edward Wadsworth used

confusingly entangled geometric forms for the ‘dazzle camouflage’ of naval

vessels.

Shocks 1914/1915

On the battlefield

Artists on active service often took the opportunity to make sketches on the

spot: of strangers, of the sufferings of the victims, of destruction. In this way they

took on the role of involved observers. These ‘brushless artists’ (Paul Klee) had to

fall back on handy formats and simple techniques.

As a rule these works were not commissioned, the artists themselves being

driven to come to terms with the enormity of the events. By contrast, it was as an

official Austrian war artist that Oskar Kokoschka made his sketches on the

Isonzo front in summer 1916.

Where the artists did have access to easels, canvases and oil-paints, then they

were mostly working on official commission, like the Frenchman Félix Vallotton

and the Englishman C. R. W. Nevinson. If, as in Nevinson’s, case the motif did

not accord with the political directives, the censorship authorities stepped in.

The disoriented, the wounded, the dead

At times the artists were not only observers, but depicted themselves as

casualties. This was especially true of some German artists. In self-portraits, they

come across as shattered, disoriented, frightened and confused. A particularly

eloquent example is the painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

A unique artistic formulation for the general physical and psychological collapse

was found by Wilhelm Lehmbruck. With his sculpture Der Gestürzte (Fallen Man)

dating from 1916, which at first bore the title Sterbender Krieger (Dying Warrior),

he created a kind of memorial.

Accusations

There were also artists who opposed the war from the outset. To reach as broad a

public as possible, they plumped for prints as a medium. And to reinforce anti-

war sentiment, they chose simple, hard-hitting images.

One of the first was the 26-year-old Willy Jaeckel, with his drastically realistic

series of prints Memento 1914/15. After making sketches on the spot, the

Impressionist Max Slevogt, who was a generation older, produced critical prints

full of cartoon-like exaggeration. The Belgian Frans Masereel used the eye-

catching succinct pictorial language of the black-and-white woodcut, as did the

Frenchman Félix Vallotton for his own sheets, which banked on popular

imagery.

A world of lines, shattered by reality

The terrors and fears of the war led some German artists to change their style, a

change which went hand-in-hand with new motifs that bore the marks of their

experiences.

Max Beckmann’s works from Kriegserklärung (Declaration of War) via

Granatenexplosion (Shell Explosion) to Leichenschauhaus (Morgue) resemble stations

along a road of suffering: direct witnesses to the shock he had undergone.

In the work of Otto Dix, too, the pictorial means reflect very directly the

bewilderment felt in the face of the carnage, the explosion, and the ruins.

Paul Klee’s drawings are invaded by prickly monsters; the very titles signal the

menacing nature of the general situation.

Prospects for the Twentieth Century 1915–1918

Fresh start in the studio

After the collapse, the artists rediscovered themselves as isolated individuals. To

the extent that they could work in the studio at all, they made a fresh start with

their art. The extreme experiences they had undergone demanded decidedly

more radical means.

George Grosz now demanded ‘Brutality! Clarity that hurts!’, and Ernst Ludwig

Kirchner wrote: ‘I am inwardly riven and immunized against everything, but I

am fighting to express this too through art.’ His pen-and-ink drawing are among

the most impressive examples of graphic art in the whole twentieth century.

A new pictorial world also opened up for Paul Klee in the years 1916/17. On an

experimental basis to start with, he laid the artistic foundation for his future

œuvre.

Max Beckmann’s radical new start in painting is immediately obvious when one

compares the two self-portraits, the one before, the other immediately after his

involvement in the war. The large, unfinished (and not for loan) Auferstehung

(Resurrection) is the subjective résumé of his war experience.

Against everything: Dada

When artists formed groups during the war, they were driven by the political

conditions. Some fled to avoid mobilization, some travelled on false passports,

some deserted. Neutral Switzerland was the venue in 1915/16 for opponents of,

and refugees from the war, such as the Romanians Marcel Janco and Tristan

Tzara, the Germans Hans Richter, Richard Huelsenbeck, Hugo Ball and Emmy

Hennings, and Hans Arp, who was from Alsace. Richter noted that he could not

understand ‘how a movement could arise from such heterogeneous elements’.

This movement was Dada.

The Dadaists were against everything, against the war, against the bourgeoisie

and against its culture. Their activities in Zurich were concentrated three areas: a

new approach to spoken language, a new approach to printed language

(typography) and the invention of the ‘Aktion’ as an art form.

Radicalized Modernism

Malevich presented his totally abstract Black Square for the first time in Petrograd

(St Petersburg) in 1915. At the same time, Vladimir Tatlin exhibited sculptures

made of objets trouvés that represent nothing but themselves. This laid the

foundations for unconditional abstraction and for the material picture of the

twentieth century.

In order to escape the war, Marcel Duchamp went to New York in the summer of

1915. Here he created The Large Glass, and applied the term ‘Ready-made’ for the

first time to his selected objects – the foundations of Concept Art.

While Picasso, after 1915, was once again working in the traditional style, which

he had previously rejected in favour of the Cubist technique, the Paris-based

Futurist Severini also made a similar turnaround, thus laying the foundations for

the Neue Sachlichkeit of the 1920s.

To avoid military service, Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà both spent time in

a military psychiatric hospital in Ferrara in 1917. There they produced

outstanding works which paved the way for Surrealist painting.

List of Artists

Pierre ALBERT-BIROT (1876–1967)

Hans (Jean) ARP (1886–1966)

Roberto Marcello Iras BALDESSARI (1894–1965)

Hugo BALL (1886–1927)

Ernst BARLACH (1870–1938)

Max BECKMANN (1884–1950)

Carlo CARRÀ (1881–1966)

Lovis CORINTH (1858–1925)

Robert DELAUNAY (1885–1941)

Otto DIX (1891–1969)

Marcel DUCHAMP (1887–1968)

Raoul DUFY (1877–1953)

Heinrich EHMSEN (1886–1964)

Conrad FELIXMÜLLER (1897–1977)

André FRAYE (1887–1963)

August GAUL (1869–1921)

Albert GLEIZES (1881–1953)

Walter GRAMATTÉ (1897–1929)

Rudolf GROSSMANN (1882–1941)

George GROSZ (1893–1959)

Otto GUTFREUND (1889–1927)

Raoul HAUSMANN (1886–1971)

Erich HECKEL (1883–1970)

Otto HETTNER (1875–1931)

Richard HUELSENBECK (1892–1974)

Willy JAECKEL (1888–1944)

Marcel JANCO (1895–1984)

Alexej von JAWLENSKY (1865–1941)

Arthur KAMPF (1864–1950)

Wassily KANDINSKY (1866–1944)

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER (1880–1938)

Paul KLEE (1879–1940)

Oskar KOKOSCHKA (1886–1980)

Käthe KOLLWITZ (1867–1945)

Alfred KUBIN (1877–1959)

František KUPKA (1871–1957)

Fernand LÉGER (1881–1955)

Wilhelm LEHMBRUCK (1881–1919)

Aristach LENTULOW (1882–1943)

Max LIEBERMANN (1847–1935)

August MACKE (1887–1914)

Wladimir Wladimirowitsch MAJAKOWSKI (1893–1930)

Kazimir MALEVICH (1878–1935)

Franz MARC (1880–1916)

André MARE (1885–1932)Frans MASEREEL (1889–1972)

Ludwig MEIDNER (1884–1966)

Jean METZINGER (1883–1956)

Gabriele MÜNTER (1877–1962)

Christopher Richard Wynne NEVINSON (1889–1946)

Emil NOLDE (1867–1956)

Francis PICABIA (1879–1953)

Pablo PICASSO (1881–1973)

Hans RICHTER (1888–1976)

Waldemar RÖSLER (1882–1916)

Luigi RUSSOLO (1885–1947)

Egon SCHIELE (1890–1918)

Gino SEVERINI (1883–1966)

Max SLEVOGT (1868–1932)

Jacob STEINHARDT (1887–1968)

Wladimir Lewgrafowitsch TATLIN (1885–1953)

Wilhelm TRÜBNER (1851–1917)

Percyval TUDOR-HART (1873–1954)

Leon UNDERWOOD (1890–1975)

Henry VALENSI (1883–1960)

Félix VALLOTTON (1865–1925)

Theo VAN DOESBURG (1883–1931)

Franz VON STUCK (1863–1928)

Éduard VUILLARD (1868–1940)

Albert WEISGERBER (1878–1915)

Ossip ZADKINE (1891–1967)

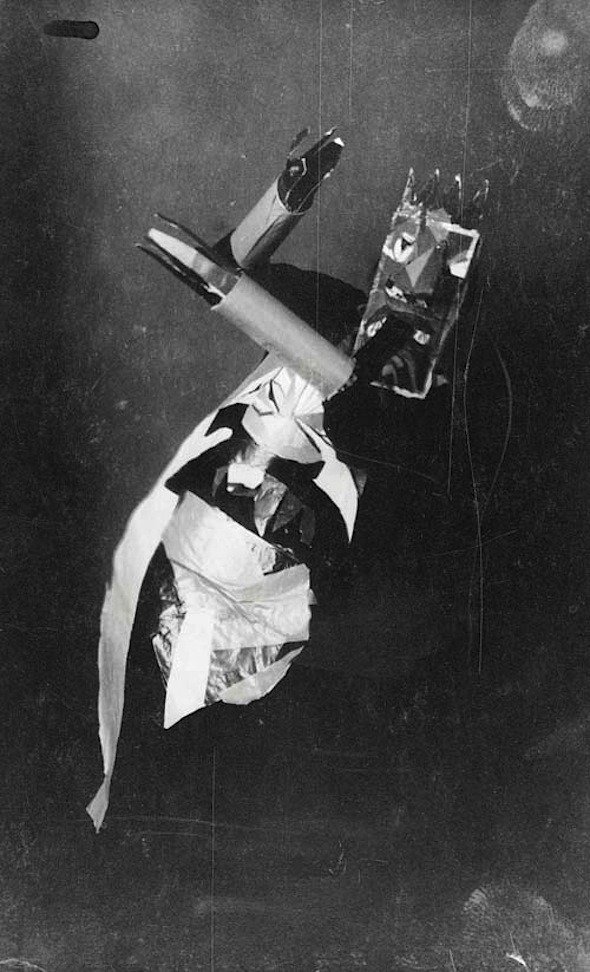

Image: Sophie Taeuber dancing with mask by Marcel Janco, 1917, Photograph

Head of Corporate Communications/Press Officer

Sven Bergmann

T +49 228 9171–204

F +49 228 9171–211

bergmann@bundeskunsthalle.de

Media Conference: 7 November 2013, 11 a.m.

Kunst und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland

Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 4 - 53113 Bonn

Opening Hours

Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.

Thursday to Sunday: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Public Holidays: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Closed on Mondays

Admission 1914 and Missing Sons

standard / reduced / family ticket

€ 10 / € 6.50 / € 16

Happy Hour-Ticket

€6

Tuesday and Wednesday: 7 to 9 p.m.

Thursday to Sunday: 5 to 7 p.m.

(for individuals only)

Advance Ticket Sales

standard / reduced / family ticket

€ 11.90 / € 7.90 / € 19.90

inclusive public transport ticket (VRS)

on www.bonnticket.de

ticket hotline: T +49 228 502010

Admission for all exhibitions

standard / reduced / family ticket

€ 16/ € 11 / € 26.50

Audio Guide for adults in German language only

€ 4 / reduced € 3