Henri Matisse

dal 2/3/2015 al 20/6/2015

Segnalato da

2/3/2015

Henri Matisse

Scuderie del Quirinale, Roma

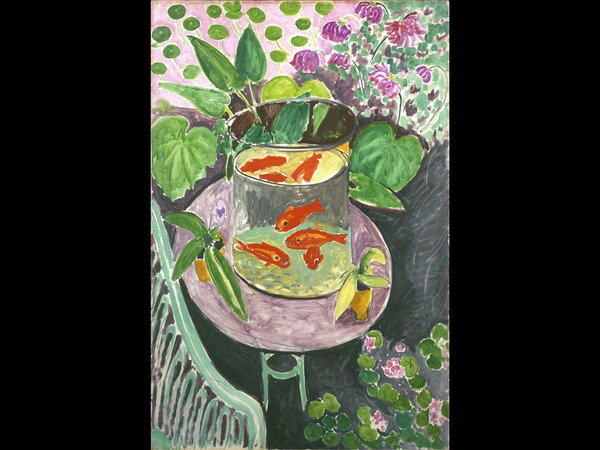

Arabesque. La fascinazione per l'Oriente negli occhi occidentali di Matisse raccontata in una mostra che riunisce circa 100 opere dei piu' prestigiosi musei del mondo. Un Oriente che, con i suoi artifici, i suoi arabeschi, i suoi colori, suggeri' un diverso spazio plastico e offri' un nuovo respiro alle sue composizioni.

----- english below

a cura di Ester Coen

“La preziosità o gli arabeschi non sovraccaricano mai i miei disegni, perché quei preziosismi e quegli arabeschi fanno parte della mia orchestrazione del quadro.”

La révélation m’est venue d’Orient scriveva Henri Matisse nel 1947 al critico Gaston Diehl: una rivelazione che non fu uno shock improvviso ma – come testimoniano i suoi quadri e disegni -viene piuttosto da una crescente frequentazione dell’Oriente e si sviluppa nell’arco di viaggi, incontri e visite a mostre ed esposizioni.

Proposta dalle Scuderie del Quirinale, promossa dal Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo, da Roma Capitale – Assessorato alla Cultura, Creatività, Promozione Artistica e Turismo, la mostra è organizzata dall’Azienda Speciale Palaexpo in coproduzione con MondoMostre e catalogo a cura di Skira editore. In esposizione oltre cento opere di Matisse con alcuni capolavori assoluti – per la prima volta in Italia – dai maggiori musei del mondo: Tate, MET, MoMa, Puškin, Ermitage, Pompidou, Orangerie, Philadelphia, Washington solo per citarne alcuni.

Curata da Ester Coen, con un comitato scientifico composto da John Elderfield, Remi Labrusse e Olivier Berggruen, Matisse. Arabesque, vuole restituire un’idea delle suggestioni che l’Oriente ebbe nella pittura di Matisse: un Oriente che, con i suoi artifici, i suoi arabeschi, i suoi colori, suggerisce uno spazio più vasto, un vero spazio plastico e offre un nuovo respiro alle sue composizioni, liberandolo dalle costrizioni formali, dalla necessità della prospettiva e della “somiglianza” per aprire a uno spazio fatto di colori vibranti, a una nuova idea di arte decorativa fondata sull’idea di superficie pura.

Henri Matisse non era destinato alla pittura, “Sono figlio di un commerciante di sementi, al quale avrei dovuto succedere nella gestione del negozio”, cerca di intraprendere la carriera di avvocato prima di diventare un artista. Sarà la sua salute a cambiare il corso della storia. Lavorava come assistente in uno studio legale di Saint-Quentin, quando nel 1890 una grave appendicite lo costringe a letto per quasi un anno. Comincia a dedicarsi alla pittura e dal 1893 frequenta l’atelier del pittore simbolista Gustave Moreau insieme con l’amico Albert Marquet. Si iscrive ufficialmente all’École des Beaux Arts nel 1895, dove insegnano molti Orientalisti.

In quegli anni vedrà molto Oriente: visita la vasta collezione islamica del Louvre in esposizione permanente e le diverse mostre che, nel 1893-1894 e soprattutto nel 1903, vennero dedicate all’arte islamica al Musée des Arts Decoratifs di Parigi. E poi, all’Esposizione mondiale del 1900, scopre i paesi musulmani nei padiglioni dedicati a Turchia, Persia, Marocco, Tunisia, Algeria ed Egitto. Matisse frequenta anche le gallerie dell’avanguardia, come quella di Ambroise Vollard, dal quale acquista nel 1899 un disegno di Van Gogh, un busto in gesso di Rodin, un quadro di Gauguin e uno di Cézanne, che influenzerà moltissimo l’opera di Matisse.

Viaggia in Algeria (1906), ne riporta ceramiche e tappeti da preghiera che nel disegno e nei colori riempiranno le sue tele da li in poi, in Italia (1907) visita Firenze, Arezzo, Siena e Padova “quando vedo gli affreschi di Giotto non mi preoccupo di sapere quale scena di Cristo ho sotto gli occhi ma percepisco il sentimento contenuto nelle linee, nella composizione, nei colori”. La visita alla grande “Esposizione di arte maomettana” a Monaco di Baviera nel 1910 – la prima mostra di arte mussulmana che influenzerà una generazione di artisti, da Kandinsky a Le Corbusier – sarà il vero spunto per un tipo di decorazione di impianto compositivo assai lontano dalle sue tradizioni occidentali. E’ a Mosca nell’autunno 1911 per curare l’installazione in casa Schukin di La danza e La musica. Nel 1912 torna in Africa, stavolta la meta è il Marocco, Tangeri la bianca. Ecco che il tailleur de lumiere, come lo battezza non a caso il genero Georges Duthuit, è sorpreso da una luce dolce e da una natura lussureggiante che andranno ad accentuare la sua cadenza armonica, musicale: “un tono non è che un colore, due toni sono un accordo”.

Matisse si lascia alle spalle le destrutturazioni e le deformazioni proprie dell’avanguardia, più interessato ad associazioni con modelli di arte barbarica. Il motivo della decorazione diventa per l’artista la ragione prima di una radicale indagine sulla pittura. E’ dai motivi intrecciati delle civiltà antiche che Matisse coglie i principi di rappresentazione di uno spazio diverso che gli consente di “uscire dalla pittura intimistica” di tradizione ottocentesca.

Il Marocco, l’Oriente, l’Africa e la Russia, nella loro essenza più spirituale e più lontana dalla dimensione semplicemente decorativa, indicheranno a Matisse nuovi schemi compositivi. Arabeschi, disegni geometrici e orditi, presenti nel mondo Ottomano, nell’arte bizantina, nel mondo ortodosso e nei Primitivi studiati al Louvre; tutti elementi interpretati da Matisse con straordinaria modernità in un linguaggio che, incurante dell’esattezza delle forme naturali, sfiora il sublime.

----- english

curated by Ester Coen

“The jewels or the arabesques never overwhelm my drawings from the model, because these jewels and arabesques form part of my orchestration.”

Henri Matisse told critic Gaston Diehl in a letter dated 1947 that “la révélation m’est venue d’Orient”: but this revelation was by no means a sudden shock. As we can tell from his paintings and drawings, it was spawned by a growing familiarity with the Orient and gradually developed in the course of the artist’s travels, encounters and visits to exhibitions and shows.

Hosted by the Scuderie del Quirinale and promoted by the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo and by Roma Capitale – Assessorato alla Cultura, Creatività e Promozione Artistica, the exhibition is produced by the Azienda Speciale Palaexpo in conjunction with MondoMostre, while the catalogue is published by Skira Editore. The exhibition will be showcasing over one hundred works by Matisse, including several of his most outstanding masterpieces – on display in Italy for the very first time – from some of the world’s leading museums such as the Tate in London, the MET and the MoMa in New York, the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the Centre Pompidou and the Orangerie in Paris, and the leading museums of Philadelphia and Washington, to mention but a few.

Curated by Ester Coen with a scholarly committee comprising John Elderfield, Remi Labrusse and Olivier Berggruen, Matisse Arabesque aims to offer visitors a perception of the influenced exercised by the Orient on the painting of Matisse – an Orient which, with its artifice, its arabesques and its colours, suggests a vaster space, a truly plastic space, infusing his compositions with a new breadth, freeing it from all formal constraint, from the need for perspective and for “lifelikeness”, opening up a space made of vibrant colours, a novel conception of decorative art resting on the idea of pure surface.

Henri Matisse was not born to become a painter – “I am the son of a seed merchant, and I was supposed to take over the business and run it in my father’s place” – in fact, he set out on a career as a lawyer before becoming an artist. It was his health that altered the course of history. He was working as a clerk in a legal practice in Saint-Quentin in 1890 when a bad attack of appendicitis put him on his back for almost a year. He took up painting, and began to frequent symbolist painter Gustave Moreau’s studio with his friend Albert Marquet in 1893, going on to officially enrol at the École des Baux Arts, where the teaching staff included numerous Orientalists, in 1895.

He saw a great deal of the Orient in these years, visiting the Louvre’s vast collection of Islamic art on permanent display as well as the various exhibitions devoted to Islamic art hosted by the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, in 1893–4 and especially in 1903. And at the Exposition Universelle in 1900 Matisse discovered the Muslim countries themselves in the pavilions devoted to Turkey, Persia, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt. He also frequented such avant-garde galleries as that of Ambroise Vollard, where in 1899 he purchased a drawing by Van Gogh, a plaster bust by Rodin, a picture by Gauguin and a painting by Cézanne, who was to have a major impact on his work.

Matisse travelled to Algeria in 1906, bringing back the ceramics and prayer mats that were to fill his canvases with their designs and colours from that time on. In 1907 he visited Florence, Arezzo, Siena and Padua: “When I see Giotto’s frescoes, I am not concerned to find out which scene of the life of Christ I have before my eyes, but I perceive instantly the feeling which radiates from it and which is instinct in the composition in every line and colours”. His visit to the great “Exhibition of Mohammedan Art” in Munich in 1910 – the first exhibition of Muslim art that was to influence a whole generation of artists from Kandinsky to Le Corbusier – was what truly inspired him to develop a form of decoration based on a style of composition light years distant from Western tradition. Travelling to Moscow in the autumn of 1911 to oversee the installation of his La Danse and La Musique in Sergei Shchukin’s home, Matisse returned to Africa in 1912, this time to Morocco and in particular to Tangier “la blanche”. It was here that the tailleur de lumière, as his son-in-law Georges Duthuit was to nickname him, was bewitched by the soft light and lush vegetation that were to underscore his harmonious, almost musical cadence: “One tone is just a color; two tones are a chord, which is life”.

Turning his back on the destructuring and distortion typical of the contemporary avant-garde, Matisse showed a greater interest in links with the models of “barbaric” art. Decoration became the primary raison d’être of his radical exploration of painting. It was in the interwoven motifs of ancient civilisations that Matisse grasped the principles for depicting a different spatial environment that allowed him to “transcend the intimistic painting” of 19th century tradition.

Morocco, the Orient, Africa and Russia in their most intensely spiritual essence, their essence most distant from the purely decorative, were to suggest new compositional patterns to Matisse. The arabesques and intricate geometrical designs found in the Ottoman world, in Byzantine art, in the Orthodox world and in the early painters whose work he had studied in the Louvre were all elements that Matisse interpreted in an extraordinarily modern manner, formulating an artistic vocabulary which ignored the precision of natural forms in order to brush with the sublime.

Patrocini:

Sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica. Proposta dalle Scuderie del Quirinale, promossa dal Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo, da Roma Capitale – Assessorato alla Cultura, Creatività, Promozione Artistica e Turismo, la mostra è organizzata dall’Azienda Speciale Palaexpo in coproduzione con MondoMostre e catalogo a cura di Skira editore.

Ufficio Stampa:

Piergiorgio Paris – Azienda Speciale Palaexpo p.paris@palaexpo.it – tel. 06 48941206

Inaugurazione 3 marzo su invito

Scuderie del Quirinale

via XXIV Maggio, 16 Roma

Orario: dalla domenica al giovedì dalle 10.00 alle 20.00 venerdì e sabato dalle 10.00 alle 22.30 L'ingresso è consentito fino a un’ora prima dell’orario di chiusura

Biglietti: Intero € 12,00 Ridotto € 9,50 Ridotto 7-18 anni € 6,00 Ingresso gratuito fino ai 6 anni