Two Exhibitions

dal 30/3/2015 al 1/5/2015

Segnalato da

30/3/2015

Two Exhibitions

Galeria Vermelho, Sao Paulo

Gisela Motta & Leandro Lima continue their investigation into man's relation with his surroundings. Ana Maria Tavares brings the facade of the Baker House into the interior of the space.

Gisela Motta & Leandro Lima

Chora-Chuva

In Chora-Chuva [Cry-Rain], Gisela Motta & Leandro Lima continue their investigation into man’s relation with his surroundings. Based on the awareness of a global environmental crisis, the duo touches on points pertinent to the current discussion concerning the problems of resource management. The show features works that talk about how mediums and media are very rapidly falling into disuse as they are replaced by more advanced techniques, and about the result of these operations.

In the installation after which the exhibition is entitled, Chora-Chuva, 2014, a total of 16 plastic pails containing water are arranged on tables as though to catch falling waterdrops invading the exhibition space. Under these pails, loudspeakers were installed in such a way as to create vibrations that simulate the effects of water dripping into them. This work, originally conceived for the last Vancouver Biennial, gains new meanings when inserted within the context of the water-supply crisis currently besetting Brazil’s largest metropolis, calling attention to the need for all of society to reflect on this problem. Motta and Lima thus spotlight a conflict in urgent need of a solution.

Water is also present in the paintings of the series Terrenos [Terrains], 2015. In these works, drawings made with enamel paint (the same type used to paint miniature models of military vehicles) resemble camouflage patterns. In the marbling technique called ebru, the paint is placed on the surface of water, and the water’s movement is transferred to the absorbent surface of the artwork. The paintings refer to views of regions of Latin America seen by satellites (represented in their color schemes). The pieces of the series Terrenos were constructed on the basis of the different parts of a tangram puzzle. This point reinforces the idea of camouflage as a development of the logical reasoning in the analysis and distinctiveness of their shapes. By referring to this sort of pattern, the artist also points to the regions represented as zones of conflict, or as zones from which, for some reason, the other is seen (or should be seen) as an enemy. Atacama, Tapajós and São Paulo are some of the places represented in the series.

Another piece linked to urban and natural landscapes is Relâmpago [Lightning Bolt], 2015. The artists created a lightning bolt made out of fluorescent tubes of the activiva type. According to the manufacturer, this type of light bulb promotes the well-being and productivity of humans, while also stimulating photosynthesis. The artists are evidently referring to man’s dependence on electrical energy, at least in the urban context.

It is important, however, to investigate other aspects of the symbolism linked to lightning bolts: scientific theories indicate that electrical discharges may have played an essential role in the origin of life. In human history, lightning was possibly the first source of fire, a milestone in the process of our evolution. Generally, lightning represents a power that is simultaneously creative and destructive, when seen from either a scientific or mythological point of view. It is simultaneously life and death; a synthesis of celestial activity and its transformative actions.

These dichotomous relations appear in other works of the show, including Beija-Flor [Hummingbird], 2013. In this piece, two tripods support an apparatus that rotates irregularly shaped fan blades, onto which the image of a hummingbird is projected. The image of this bird – who lives only in the Americas – is formed on a transparent surface, like a holography. The propellers fragment the originally white projection, and its color shifts to all the colors of the spectrum due to a nonsynchronicity between the projector and the fan blades. It is as though this nonsynchronicity gave rise to this image from the animal kingdom. It is something natural that emerges based on the insufficiency of the electronic apparatus.

insufficiency of media is also present in the video Horizonte [Horizon], 2015. In this work, guitar strings form waves of different size and length based on the incapacity – or incompatibility – of the video camera to capture the vibrations generated by the string instrument.

In Bugado [Bugged], 2014, the back of an LCD monitor was removed, making it semi-transparent. Behind the screen, the artist installed an energy-saving compact fluorescent light bulb. The monitor continues to work, though we also see the light bulb behind the image it is displaying. The image is that of flies that seem to be circling around the light bulb. The observers get the impression that they were looking at the vestiges of a material culture. Thus, what is left functioning in this ruin is what allows us to see the nature around it, in this case, the image of the flies that circle the object.

Finally, in Deposição [Deposition], 2013, disuse appears in the form of an accumulation of printed encyclopedias cut like topographic drawings to resemble stalagmites. They therefore refer to a sedimentation of materials that are detached from their original context and begin to structure a shape made up of residues.

----

Ana Maria Tavares

Sinfonia Tropical para Loos

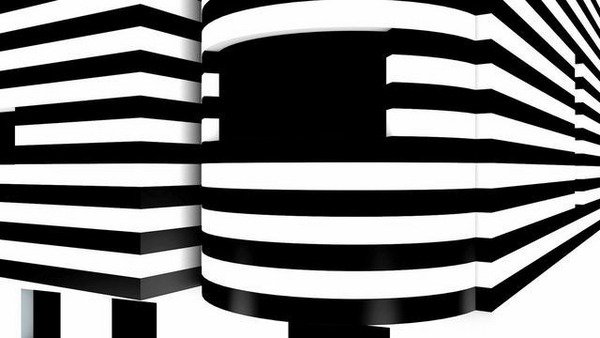

In 1927, the Czech modernist architect Adolf Loos (1870 –1933) created a never-built design for the home of Afro-American singer and dancer Josephine Baker (1906–1975). The design was based on the revamping of two existing houses on a corner of Avenue Bugeaud, in Paris. The residence, whose exterior walls were to be decorated with horizontal stripes of black and white marble, was to have small, deeply inset windows to ensure the privacy of its illustrious inhabitant, while also keeping the attention focused on the house’s interior (as was prefer by Loos). At the center of the house there was to be a pool that would pierce through two floors of the building with windows on the lower floor for underwater viewing, allowing Josephine’s guests to watch her body slicing through the water. The design for both the façade and the pool evince modernist architecture’s obsession for surfaces.

In the solo show Sinfonia Tropical para Loos [Tropical Symphony for Loos], Ana Maria Tavares seeks a path running counter to that of the surface. In the installation Parede para Loos [Wall for Loos], the artist brings the façade of the Baker House into the interior of the space. Tavares puts the stripes of the original exterior design on all the walls circling around the exhibition space, overlaying them with a projection that conveys the spectator from the outside of the house into its interior. In the video, the camera moves along the building’s façade and its opaque windows until the latter are dissolved in a view of tropical nature. This interplay between the natural world and the regulatory modernist architecture is repeated until it immerses the spectator into the pool at the center of the house. We then see ourselves encapsulated both by the pool as well as by an architectonic structure created by the artist, called Bunker, which seems to contain the pool in the video. It is at this point that the exterior and the interior become equally fascinating, revealing a core theme often ignored in discussions about modern architecture: its disciplinary function historically linked to the medical science of eugenics. While eugenics was a discursive project that provided a structure for cultural prescription and medical-moral investigation, it is also found in, and interacts with, the modernist discourses concerning alterity and the search for a national identity. From this standpoint, Tavares’ installation makes us question whether Loos’s obsession for keeping the attention focused on the interior of his designs is perhaps linked to a view of a sanitized identity: eugenics.

Also in the pieces called Vitrines, da série Paisagens Perdidas (para Lina Bo Bardi) [Display Cases, from the Lost Landscapes Series (For Lina Bo Bardi)], the interior is raised to the exterior. Working with museum display elements conceived by Lina Bo Bardi to serve in conjunction with her celebrated glass display easels – and that were in fact never built – Tavares creates bodies suspended in the air that reveal their empty interiors, though surrounded with images of the teeming natural world printed on the glass surface of each of their faces. It seems that Tavares reveals the modernist initiative to organize, select and contain the natural as something that conflicts with its project for the formulation of identity.

Finally, Sinfonia Tropical para Loos, resulting from the artist’s investigations for the exhibitions Natural-Natural: Paisagem e Artifício (2013), e Atlântica Moderna: Purus e Negros (2015), features a large number of Vitória Régias [Victoria amazonica lily pads] encapsulated by Plexiglas boxes with stainless steel structures and divided into two sets, designated as being for the Brazilian rivers Cocó and Purus and Negro, respectively. Like the other works in the exhibition, the Vitória Régias compose a critical apparatus that, according to the critic and curator Fabiola Lopez-Durán, “relativizes the supposed tropical threat and the so much desired sterile geometry of the modern aesthetics”. Here the poetics, however, refers to the legend of Naiá, a Tupi-Guarani Indian girl who was so fascinated by the reflection of the Moon in the water that she got too close to a river and drowned. The Moon (Jaci) felt sympathetic and recompensed the Indian girl for her sacrifice, by transforming her into a unique and perfect “Water Star” – the Victoria amazonica. There is an evident parallel between the legend of Naiá and the myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own image and pined away on the banks of the lake of Echo, admiring his own reflection in the water. The son of the river god Cephissus and the nymph Leiriope, was transformed by Aphrodite into a flower (the narcissus), in which form he eternally tries to contemplate his image in the reflection of the water.

If we recall Parede Niemeyer [Niemeyer Wall] – which Tavares constructed in 1998, re-creating a large wall of mirrors designed by Oscar Niemeyer for the Cassino da Pampulha (Belo Horizonte), and which the artist sees as a synthesis of the modernist utopia – we can understand Jaci’s reward as actually being a sentence, making Naiá a hostage of her flower form; just as our fellow citizens, when they admire Niemeyer’s mirror, contemplate the never fulfilled promise of the Brazilian modernist project.

Image: still from the “Wall for Loos” video

Press Contac: gabriel@galeriavermelho.com.br

Opening: March 31 at 8 p.m

Galeria Vermelho

Rua Minas Gerais, 350

Sao Paulo Brasile

Opening Hours:

Mon - Fri 10am to 7pm, Sat 11am to 5pm