A Picture of Britain

dal 14/6/2005 al 4/9/2005

Segnalato da

Hamish Fulton

Graham Sutherland

David Cox

Cedric Morris

Patrick George

John Constable

JMW Turner

Paul Nash

Richard Long

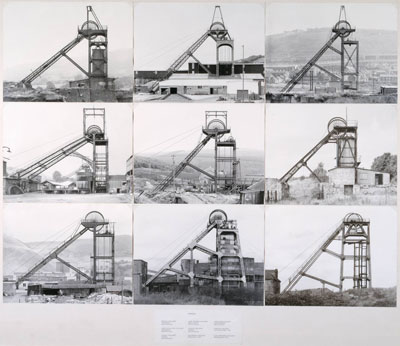

Bernd and Hilla Becher

14/6/2005

A Picture of Britain

Tate Britain, London

An exhibition exploring how British landscape has inspired artists for three hundred years. It also examines how artists have influenced and changed the way we look at and think about landscape. This show takes you on a six-part journey across the country, from the Scottish Highlands to the South Downs. By focusing on a broad range of artistic responses to landscape, it also examines ideas about travel, nationhood, industrialisation and notions of the rural. Each section characterises the British countryside through the eyes of different artists. Works by John Constable, JMW Turner, Hamish Fulton, Paul Nash, Richard Long and many others

An exhibition celebrating the British Landscape

A Picture of Britain explores how British landscape has inspired artists for three hundred years. It also examines how artists have influenced and changed the way we look at and think about landscape.

This exhibition takes you on a six-part journey across the country, from the Scottish Highlands to the South Downs. Each section characterises the British countryside through the eyes of artists such as John Constable, JMW Turner, LS Lowry, Paul Nash and Richard Long. By focusing on a broad range of artistic responses to landscape, the exhibition also examines ideas about travel, nationhood, industrialisation and notions of the rural.

---

The Romantic North

'Man, Nature and Society'

This room looks at northern England, mainly Cumbria, Yorkshire and Northumberland. Its themes are the discovery of nature, and the industrial city.

The north, outside its towns, was long regarded as forbidding - ''mostly rocks' according to one early traveller. But changing attitudes to nature and wilderness made it more fashionable during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Lake District became an English Arcadia, reminding ''Picturesque' tourists of paintings by Claude Lorrain. Wilder scenery, like Yorkshire's Gordale Scar or the bleak Northumberland coast, appealed to a taste for the awe-inspiring and 'Sublime'.

Artists like JMW Turner toured the north, filling exhibitions with views of its landscapes and architectural heritage. Wordsworth's poems written in the Lake District describe the moral and religious impact of his sense of harmony with nature. The Brontës personified the Yorkshire moors in the untamed emotions of their characters.

In the twentieth century the developing relationship between the country and the city became both closer and more tense. Artists often viewed the industrial landscape from the surrounding countryside or, like LS Lowry, saw it as a parody of the natural scene, where trees are replaced by forests of mill chimneys.

---

The Mystical West

Myths and Megaliths

This room looks at a large area of ancient Britain, forming a triangle between Stonehenge, north Wales and St Ives in Cornwall. Its central theme is that of the mystical landscape of megaliths, burial mounds and Celtic legend.

Stonehenge has fascinated artists and writers since the seventeenth century. Its ancient stones and earthworks create a powerful sense of mystery and wonder. Writers such as the antiquarian William Stukeley believed it was a druidical site and many artists imagined how it might have been used for ancient rituals. Today it is visited by tourists and latter-day druids and is still studied by archaeologists.

Eighteenth century tourists in search of ‘Picturesque’ landscape would have preferred the Wye Valley and ruins such as those at Tintern Abbey. Inspired by the writer William Gilpin, they looked at landscape as one might a picture, seeking pleasing combinations of form and balanced views with nothing too alarming or bleak. A taste for the wilder mountainous landscape of north Wales, however, also became popular at this time. Welsh myths and legends as well as the unspoilt scenery and local customs made places such as Betws-y-Coed popular destinations.

In the twentieth century, in search of further Celtic landscape mysteries, artists such as Graham Sutherland have worked in south Wales, while St Ives in Cornwall was a major artists colony from the 1920s.

---

The Heart of England

Paradise and Pandemonium

This room looks at the area between Nottingham, Wolverhampton and Oxford. Its central themes are the industrial landscape of Derbyshire and the Black Country, and the later rejection of industrialisation by artists who moved to the Cotswolds in search of a rural idyll.

The geology of sites such as Cresswell Crags and of the Peak District became of increasing interest to a nation fascinated by its past and the potential of its natural resources. Joseph Wright’s images of iron forges and cotton mills focus both on the new world of industry and the beauty of its natural setting. Artists celebrated the Iron Bridge and blast furnaces at Coalbrookdale, and tourists visited them enthusiastically.

But by the early nineteenth century many people began to find the industrial ‘Heart of England’ ugly and oppressive, as it grew ever greater in size. A few artists such as Edward Wadsworth sought grim beauty in the slag heaps and chimneys of the midlands. Most turned to an ideal of a pre-industrial world. Following William Morris, they found in the Cotswolds an old England where they could create a slower world of traditional arts and crafts, in a landscape of gentle hills and charming stone-built houses.

---

The Home Front

'War and Peace'

Britain has not experienced a successful invasion since 1066. But fears remained along the vulnerable south-eastern coast of England, especially with the advent of aerial warfare. During the second world war, with the Battle of Britain in 1940, war finally came to mainland Britain. This resulted in highly innovative landscape paintings by Paul Nash and other war artists.

From the eighteenth century onwards, the southern counties and coastline were the first line of defence, above all for London. But increasingly they also became the playground of the metropolis, giving rise to modern seaside tourism. The seaside resort was invented during the eighteenth century. Visitor numbers grew rapidly during the Victorian period, with the opening of railway links. By 1911 over half the population of England and Wales made one seaside trip per year. Many paintings included here, by JMW Turner, John Constable, William Dyce, Walter Sickert and others, picture this national pastime.

The appeal of the coast and the countryside as an escape from the city also satisfied concerns about the moral and physical health of the nation. Rural and coastal villages came to represent an unspoilt element of national culture, in perfect harmony with nature. This ideal played an important part in war propaganda, as a traditional way of life worth defending.

---

The Flatlands

'The Nature of Our Looking'

This room looks at East Anglia, bounded by the Fens, North Sea and Wash. Its theme is the contribution of this predominantly agricultural landscape to the emergence of naturalism.

East Anglia was for centuries isolated and self-contained. For admirers of the 'Picturesque' or 'Sublime' it lacked pictorial qualities. Yet through the work of artists born in the region, it has become the epitome of English rural scenery.

Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable were natives of Suffolk. They, like painters of the Norwich School, were inspired by Dutch landscape paintings in local collections – a legacy of trading links across the North Sea. They painted what they knew and saw, close to the land and beneath the huge skies that Constable called his 'chief organ of sentiment'. Constable sought a 'natural painture', studying from nature in what became known as 'Constable Country', on the Suffolk-Essex border.

Realism also marked the descriptions of rural life by East Anglian writers like Robert Bloomfield and George Crabbe, and the Victorian photographs taken in the Norfolk Broads by PH Emerson. In the early twentieth century William Coldstream continued Constable's empirical, objective view of nature. Today, Justin Partyka's ongoing photographic survey The East Anglians maintains the regional tradition.

---

Highlands and Glens

'Land of the Mountain and the Flood'

For many people, the Highland region is Scotland. Many Scots have found their national identity in the landscape, costume and associations of this region. Nations often adopt a 'rural face' in reaction to modernisation. But the identification of Scotland with a region formerly perceived, by Lowlanders and non-Scots alike, as barren and uncivilised, is a result of a more particular history: the country's relationship with England.

The creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, by the Act of Union of 1707, gave this way of picturing the Highland landscape its unique force. It produced a sense of crisis for the nation's independence and cultural distinctness, and a determination to identify and preserve what was unique about Scotland.

The Romantic period saw Scottish identity subsumed within a myth of the Highlands. Fostered by British royalty and the social elite, this reached its climax in the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901). It found its most potent visual expression in landscapes with historical and literary associations, or awe-inspiring wilderness, epitomised by the work of Edwin Landseer and Horatio McCulloch. Such imagery still resonates today, despite the dynamism and international outlook of modern and contemporary Scottish art.

---

Image: Bernd and Hilla Becher - Pitheads (1974)

Tate Britain

Millbank SW1P 4RG

London