WallCeilingFloor

dal 27/1/2007 al 3/3/2007

Segnalato da

27/1/2007

WallCeilingFloor

Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham

William Anastasi, Donald Judd and Fred Sandback. The exhibition presents selected works of three seminal artists who, beginning in the 1960’s, explored not only the forms and uses of the materials they used to create their objects, but also the relationships between these objects and the physical limits of the spaces in which they were to be placed. The key element is less the form than the open space defined by the gallery’s physical constraints, then transformed by the intrusions of the works into that space.

Works by William Anastasi, Donald Judd, and Fred Sandback

Curator: Gail Andrews

The exhibition presents selected works of three seminal artists who, beginning in the 1960’s,

explored not only the forms and uses of the materials they used to create

their objects, but also the relationships between these objects and the

physical limits of the spaces in which they were to be placed.

Before such explorations, art had traditionally been thought to be some

form of an object itself, whether hung on a wall or placed on a pedestal.

That assumption—the independence of the object from its framework—was and

is challenged by the works of Fred Sandback (1943-2003), Donald Judd

(1928-1994) and William Anastasi (b. 1932). Each of the works in this

exhibition should be seen not only as independent objects but also in

relationship to the walls, ceilings or floors. In fact, in certain of the

works, a key element is less the form of the chosen material than the open

space of the so-called “white box" defined by the gallery’s physical

constraints, then transformed by the intrusions of the works into that

space.

Fred Sandback used for his sculptures ordinary acrylic yarn. With

variously colored yarn, Sandback drew lines in space that generated

spatial tensions above, below and laterally within the space in which they

were installed. The dimensions of the principal sculptures in this

exhibition, The First of Sixteen Two-Part Variations of Two Diagonal

Lines, were conceived by Sandback to be variable in dimension depending

upon the three dimensions of a given space. They consist of two diagonal

stretches of cardinal red yarn, one ascending from a lower corner of the

room to the ceiling, the other descending from an upper corner of the room

to the floor. The sculptures produce a dynamic of competing spatial forces

that change as the viewer moves through the space. The viewer’s

interaction with the Diagonal Lines is itself a “variation" on them, such

that the individual perceptions of the viewer become indispensable

elements of the artwork.

Donald Judd mastered the art of precisely cut and mathematically ordered

structures, often fabricated in a series of rectangular prisms. Judd

typically used common industrial materials such as plywood, stainless

steel or Plexiglas in his work. His sculptures frequently take on the form

of stacks of “boxes" hung on a wall or placed directly on the floor; and

often incorporate elements of color, whether by means of Plexiglas

elements bonded to metal, or enameled or anodized paint applied directly

to the metal surfaces.

In all of his works, Judd used simplified forms to delineate and deform

the space surrounding each of them. The works themselves seem to bond with

the wall or floor. For example, his Wall Project (No. 32)—shown in this

exhibition for the first time in a museum setting—consists of two

galvanized iron plates inset into the wall in intervals spaced to divide

the wall into thirds. Judd’s instructions for fabricating the work require

that the dimensional ratio of the wall recesses to the height and length

of the plates equals 1:2:3. As set into the wall, the viewer is free to

question whether each iron plate is a separate “art object," whether the

two together are a work of art, whether the cut-out wall as a whole is the

work, whether the shadows within the recesses are elements of the work.

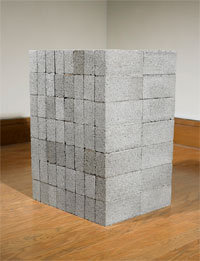

William Anastasi’s work is frequently not limited to a characteristic set

of materials or formal concerns. His works at times are defined by

mathematically determined limits, as with What Was Real in the World, a

stack of 112 concrete bricks laid in 7 tiers of 16 bricks each, a grouping

one might see on a construction site. Other works depend in large part on

chance determinants, as with Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, a work created by

draping a videotaped performance of that symphony over two nails spaced at

the width of the artist’s arms stretched upward and outward diagonally.

Anastasi’s works in this exhibition reflect his intention to de-construct

the gallery site, whether by removing part of the wall’s own structure,

“drawing" lines on the wall by means of the shadows cast by a series of

embedded nails, or creating a plane of light in the space between the wall

and the ceiling by angling two sets of track lighting fixtures at each

other. The result is that the viewer has to rethink his perceptions of the

walls, ceiling and floor of the gallery, and what in fact is the art they

contain.

Image: William Anastasi - What Was Real in the World (1964)

The Birmingham Museum of Art

2000 Eighth Avenue North - Birmingham

Museum Hours: Tuesday - Saturday 10am - 5pm; Sunday 12 - 5pm