Hannah Hoch

dal 15/1/2008 al 3/5/2008

Segnalato da

15/1/2008

Hannah Hoch

Tinguely Museum, Basel

The exhibition assembles the early collages and paintings of her Dada-period right after the First World War, the works of the 1930s and 40s. Late works that manifestly anticipated Pop Art by their motifs and bright colours, and were Hoch's reaction to scientific discoveries of the day.

The Museum Tinguely presents the first extensive survey in Switzerland dedicated to Hannah Höch (1889-1978), the sole woman member of the group Dada Berlin. The exhibition covers the period from her early Dada years during and immediately following the First World War through the 1920s, a fertile phase in her career during which Höch was in contact with numerous important avant-garde artists such as Kurt Schwitters, Hans Arp, Theo van Doesburg. She collaborated in part with them, producing masterly collages, profound yet ironical. During the 1930s and ‘40s, she worked in total retirement and secrecy – and her works contain a cryptic criticism of the National Socialist regime. Her late works, less known, in which she appears to anticipate Pop Art by her themes and colours, were her reaction to new scientific discoveries of the day. To close the exhibition, a section will be dedicated to Höch’s garden – a recurrent theme throughout the artist’s oeuvre.

Having exhibited in the course of the last years various important artists of the Dada movement, the Museum Tinguely is the ideal platform for a presentation of Hannah Höch’s work. But, as the constant defender of individualism, Höch is furthermore close to the kinetic artist Jean Tinguely and his source of inspiration, anarchism.

The exhibition was conceived in close collaboration with the Berlinische Galerie, seat of the Hannah Höch archives; it is organised in a chronological order and divided into five sections, opening with Höch’s large-scale photo-collage Lebensbild that the artist created in 1972/1973 so to speak as a sort of visual autobiography. The collage harks back to numerous important works that the visitor can encounter throughout the exhibition.

dada cordial: Höch, Hausmann and DADA Berlin

Hannah Höch was born in 1889, into a middle-class family in Gotha, where she spent her youth. She studied in Berlin under Emil Orlik at the Institute attached to the Museum of Applied Arts and financed her studies by working as a draughtswoman creating needlework patterns for the publisher Ullstein. In 1915, she met Raoul Hausmann, with whom she had relationship until 1922; the affair was a passionate one but for Höch also difficult as Hausmann, who had been married since 1908 to Elfriede Schaeffer, was not willing to leaving his wife and daughter. He attributed the difficulties of their affair to Höch’s “patriarchal-authoritarian” upbringing which had marked her and which, in his opinion, she had to overcome.

Though difficult for Höch in her private life, these years were extremely fruitful for her as an artist and the young woman was able to assert her position within the male circle of egocentric Berlin Dadaists – Hausmann, Johannes Baader, George Grosz, Richard Huelsenbeck and John Heartfield – through her masterly, though amusing-symbolical collages and objects. Thus, in the summer of 1920, she participated with works in the legendary “First International Dada Fair”.

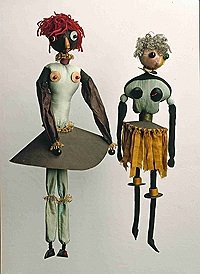

Main works in this phase of her career such as the collage Dada-Rundschau as well as the two Dada-Puppen reveal Höch to be an alert and witty commentator of the political and social changes after the First World War.

Equilibrium: ornament, abstraction and concretion

In the autumn of 1920, Höch undertook to walk on her own from Berlin to Rome, thereby signalling not only a geographical but also an emotional distance and her urge for independence, before the Berlin Dada Group was actually dissolved and she left Hausmann.

Only now was Höch free to embark on her relationships with artists such as Hans Arp, Theo von Doesburg and his wife Nelly, El Lissitzky, Piet Mondrian, László Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters and others, with whom she collaborated on an artistic level. Thus a network of artistic friendships developed throughout Europe. Staying with friends in Holland in 1926, she met the authoress Til Brugman with whom she lived until 1935 in The Hague, and later in Berlin.

In these years, Höch created a varied and multiple œuvre that reflects her urge for personal and artistic freedom. Her earlier activity in the applied arts of fashion and illustration proved to be of great use.

A rich selection of paintings such as Roma or Die Journalisten, collages like Schnurenbild or Das Sternfilet, drawings and documents illustrate this artistically fertile decade of liberation and exchange.

Wilder Aufbruch (brutal departure): survival under the Nazi regime

Already before the Nazis took over power, the political and cultural climate in Germany had changed drastically. After 1933, the modern trends in literature and in the arts came under stronger attack and numerous avant-garde artists were obliged to leave the country. Even Hannah Höch’s works were mentioned prominently in defamatory publications and exhibitions such as Säuberung des Kunsttempels and „Entarte ‚Kunst’“ in 1937. The hostile climate and banishment led Höch to retire all the more within herself, especially since she was also seriously ill at the time. In 1939, she retired to a small house in Berlin-Heiligensee – an “ideal spot to be forgotten”, where she was able save herself as well as numerous works of art of her avant-garde friends from seizure by the Nazis, and also where she could work in secrecy. Paintings such as Die Spötter or Wilder Aufbruch are a clear-sighted commentary of the circumstances that prevailed and in which critical voices were silenced brutally.

Voyage toward the unknown: vitality and the oeuvre of the late period

The end of the Second World War meant for Hannah Höch as for many other artists freedom from their artistic gag and the end to an existential threat. Already in the late 1940s, Hannah Höch was considered not only an important historical witness of the beginnings of modern art in Germany, but over and above the significance of her contribution to modern art was also recognised.

Yet, Höch did not wish to pass off simply as a historically significant artist. And until her death in 1978 she continued to produce (as one of the few left over from the Dada art scene) a valid and virtuoso late oeuvre that received strong impact through colour photography that was increasingly available. The exhibition presents a number of these virtuoso collages in which the artist literally works with the colours of the sections at her disposal as with “paint”.

Wenn die Düfte blühen (When perfumes blossom)...: Hannah Höch’s garden

It was not only with the enforced retreat to her house in Berlin-Heiligensee that motifs such as plants, nature and garden played an important role in Höch’s work: in its vulnerability, the plant appeared to her to be the pendant to human sensitivity and the image altogether of human existence.

The garden as a place of freedom and beauty, of the wondrous and the strange, and as Höch’s actual global artwork – a true utopia in which could be realised the autarchy and multiplicity that Höch yearned for.

The last room in the exhibition thus presents works from various phases in her career on the theme of nature, plant and garden. Various films show the artist in her “vegetal collage”.

This exhibition conceived in collaboration with the Berlinische Galerie has received additional loans for Basel from Swiss and German collections, thus enabling a representative survey of the life of this extraordinary artist.

The catalogue has been published by Hatje Cantz, with texts by Ralf Burmeister, Maria Makela, Werner Hofmann, Karoline Hille, Bettina Schaschke, Jörn Merkert and Janina Nentwig. c. 220 pp., num. col. and b&w ill. German edition, bound with dustcover, as well as a special brochure for the Basel venue with texts by Guido Magnaguagno and Heinz Stahlhut, and an illustrated list of works. (CHF 59)

For further information:

Dr. des. Heinz Stahlhut, Exhibition Curator.

Tel. + 41 61 688 97 93. E-mail : heinz.stahlhut@roche.com

Laurentia Leon, Press. Tel. + 41 61 687 46 08. E-mail : laurentia.leon@roche.com

Tinguely Museum

Paul Sacher-Anlage 1, Basel