L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

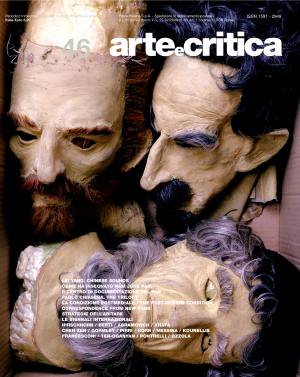

Arte e Critica Anno 13 Numero 46 aprile - giugno 2006

La Condizione Postmediale

Domenico Quaranta

Una mostra al Centro Conde Duque di Madrid è l'occasione per ripercorrere il pensiero sulla nostra era postmediale, da Rosalind Krauss a Peter Weibel

trimestrale di cultura artistica contemporanea

Intervista a cura di / Interview by Chiara Sartori

23 COME HA INSEGNATO NAM JUNE PAIK

di Daniela Palazzoli

24 IL CASO CIPRO. L’ARTE RICOSTRUISCE LA SOCIETÀ

di Claudia Zanfi

25 Il CENTRO DI DOCUMENTAZIONE DEL PAN

Intervista a Marina Vergiani a cura di Roberto Lambarelli

26 PAOLO CHIASERA. THE TRILOGY

Intervista a cura di / Interview by Daniela Bigi

30 Correspondence from new York

di / by Daniela Palazzoli

33 CALENDARIO TASCABILE

di Arturo Schwarz

36 LA CONDIZIONE POSTMEDIALE

The Post-medium condition

di / by Domenico Quaranta

40 PENSIERI IN CHIAROSCURO V

di Alberto Boatto

42 video invitational-Video in tutti i sensi

Hans Op de Beeck, Bjørn Melhus, Tobias Collier, Runa Islam

di Marco Ligas Tosi

43 MIART. MERCATO E CULTURA

Intervista a Donatella Volontè a cura di Roberto Lambarelli

44 STRATEGIE DELL’ABITARE

Intervista a Gabi Scardi a cura di Roberto Lambarelli

46 RIPENSARE IL METODO

di Claudio Vagnoni

46 LA DIDATTICA DELL’ARTE. UN PUNTO DI VISTA LONDINESE

di Sarah Ciacci

47 L’ETà NOMADE. UN LABORATORIO NELLA CITTà DELLE ARTI

49 NATURA/SOGNO/MATERIA. APPUNTI SU GIOVANNI OZZOLA

di Marco Mazzi

50 LE BIENNALI INTERNAZIONALI. Nuove modalità di approccio

di Lorenzo Bruni

53 WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES THESE CITIES SO APPEALING?

Attraversamenti tra Berlino e Torino

di Carmen Lorenzetti

56 Thomas Hirschhorn

57 Simone Berti

58 Marina Abramovich

59 Sisley Xhafa

60 Chen Zen

61 Antony Gormley

62 Alfredo Pirri

62 Roni Horn

63 Vittorio Messina

64 Jannis Kounellis

64 Luca Francesconi

65 David Ter-Oganyan

65 Gioacchino Pontrelli

1985. Trent’anni fa inaugurava il Castello di Rivoli

Roberto Lamabarelli

n. 82 estate 2015

Céline Condorelli

Massimiliano Scuderi

n. 80 primavera 2015

Note su Benoît Maire, Renato Leotta, Rossella Biscotti

n. 79 ottobre-dicembre 2014

Ah, si va a Oriente! Cantiere n.1

Daniela Bigi

n. 78 aprile-giugno 2014

Gli anni settanta a Roma. Uno sgambetto alla storia?

Roberto Lambarelli

n. 77 gennaio-marzo 2014

1993. L’arte, la critica e la storia dell’arte.

Roberto Lambarelli

n. 76 luglio-dicembre 2013

------------english below

Una mostra al Centro Conde Duque di Madrid è l'occasione per ripercorrere il pensiero sulla nostra era postmediale, da Rosalind Krauss a Peter Weibel

“Il messaggio è il messaggio, chi se ne frega del medium”. Questa boutade, firmata 0100101110101101.ORG, potrebbe essere adottata a emblema di un processo ormai quasi compiuto, e che comincia a essere etichettato come “condizione postmediale”: il passaggio da una impostazione che insiste sull'utilizzo dei nuovi media per fare arte, e sullo sviluppo dello “specifico” di un mezzo, a un'altra che dà i nuovi media per scontati, elementi imprescindibili di una cassetta degli attrezzi da cui pescare con disinvoltura.

In realtà, l'approccio che sta dietro al termine “postmediale” ha una lunga storia: più lunga, probabilmente, del termine stesso. Non a caso, Rosalind Krauss1 si serve di questo termine in un bel testo del 1999, in riferimento agli anni Settanta, che vedono da un lato il superamento dell'approccio greenberghiano, dall'altro il declino, in ambito video, della riflessione sulla “specificità mediale”. Ma è innegabile che la diffusione, agli inizi degli anni Novanta, dell'home computer, di Internet, di strumenti di comunicazione accessibili e alla portata di tutti abbia prodotto un revival mcluhaniano, e il riemergere di una riflessione concentrata sul mezzo, sulle sue caratteristiche tecnologiche e sulle sue implicazioni contenutistiche. In particolare, la critica della Net Art è piena di riferimenti allo “specifico del mezzo”, una teoria che andava rispolverata, banalmente, anche solo per distinguere l'arte che usava la Rete come “medium” da quella che la sfruttava come semplice strumento di diffusione. Parallelamente, i primi esperimenti di arte in Rete si contraddistinguono per un approccio concentrato sul mezzo, sui suoi limiti e le sue caratteristiche tecniche, non dissimile da quello che spingeva Nam June Paik a intervenire, con un magnete, sul flusso video.

Insomma: se possiamo concordare con Rosalind Krauss che la postmedialità inizi con Broodthaers, dobbiamo riconoscere che essa ha conquistato la sua definitiva maturità solo in questo primo decennio del secolo, quando i media, la loro estetica e le loro metafore sono definitivamente entrati a far parte della nostra quotidianità. Solo quando buona parte di noi ha in tasca un dispositivo che gli consente insieme di parlare, scrivere, fotografare, girare filmati e ascoltare musica; solo quando nella copertina di buona parte dei libri scopriamo annidati dei chip RFID; solo quando risulta difficile passare una settimana senza ricorrere a Internet, o scovare un alimento che non contenga ingredienti geneticamente modificati possiamo affermare con certezza che il problema non è più come servirsi dei media per fare arte, ma come farne a meno.

Da quanto detto si può già intuire una cosa: quale straordinario alibi la “condizione postmediale” fornisca a chiunque sia interessato a approfittare dell'hype che si sta creando, in campo artistico, attorno alla cosiddetta “New Media Art”. È logico: se la New Media Art è un ambito circoscritto e difficile da gestire, c'è ben poco, oggi, che non possa essere definito “postmediale”. Ecco allora, ad esempio, le teorie sulla pittura della “Google Generation”, che sembrano riproporre, a tre lustri di distanza, la bufala teorica del medialismo.

Sia ben chiaro: non si sta mettendo in dubbio la possibilità di una “pittura postmediale”, né l'idea stessa di “postmedialità”: ma credo che questo concetto, così efficace e intuitivo, richieda di essere arricchito di ulteriori livelli di senso, pena il rischio di essere svuotato prima ancora di avere fortuna.

L'espressione “era postmediale” viene coniata all'inizio degli anni Novanta da Félix Guattari2 per indicare l'era delle nuove tecnologie dell'informazione, che succede a quella dei mass-media. Secondo Guattari, le nuove tecnologie (Internet in testa) implicano una ridefinizione del tradizionale rapporto tra produttore e consumatore, e l'avvento di nuove pratiche sociali legate ai media. L'espressione ha un discreto successo nell'ambito della critica dei media, che se ne serve – sulla scorta di Guattari – come sinonimo dei media digitali, che superano la mediazione tradizionale opponendo ai vecchi media una strutturazione decentrata e non gerarchica (rizomatica), consentendo un utilizzo diffuso, inglobando e rimediando i vecchi media3.

Contemporaneamente, la critica musicale lo innesta sulle teorie del remix, della riappropriazione di suoni e strumenti e del ruolo creativo dell'ascoltatore4. In ambito artistico, se da un lato Rosalind Krauss si serve del termine anche nell'ottica del superamento della nozione greenberghiana di “mezzo”, dall'altro lo spagnolo José Luis Brea5 lo adotta in riferimento a quelle che lui chiama “comunità Web di produttori di media”, che rinnovando le ambizioni delle avanguardie si fanno produttori, dal basso, dei loro stessi strumenti.

Ma bisogna riconoscere a Postproduction6 di Nicolas Bourriaud – in cui, peraltro, il termine “postmedia” non compare – il merito di aver fatto fare a questa teoria un salto di qualità. Secondo Bourriaud l'arte contemporanea, anche quella che non usa i media, desume da questi ultimi nuovi modelli di produzione, adottando le strategie del remix e della postproduzione, e dando luogo a lavori che non sono altro che nodi di un più ampio flusso di informazione. Il “postproduttore” di Bourriaud non ha nulla di diverso dagli “operatori postmediali” di Slatter; il salto di Bourriaud consiste nel dare per avvenuto l'ingresso dell'arte contemporanea – anche di que lla che coi nuovi media sembra avere poco a che fare – nella postmedialità. O, per dirla con le parole di Peter Weibel: “... i nuovi media non sono solo un ramo nuovo nell'albero dell'arte, ma hanno trasformato lo stesso albero dell'arte... il successo intrinseco dei nuovi media risiede non tanto nel fatto che abbiano introdotto nuove forme e possibilità per l'arte, quanto nel fatto che ci abbiano resi in grado di approcciare in modo nuovo i vecchi media artistici e soprattutto che li abbiano tenuti in vita forzandoli a intraprendere un processo di trasformazione radicale.”7 Con queste parole, il direttore dello ZKM di Karlsruhe apre l'ultima parte di La condición postmedial, un lungo testo che introduce in catalogo la mostra Condición Postmedia, transitata alla Neue Galerie Graz e ora al Centro Cultural Conde Duque di Madrid. Curata da Elisabeth Fiedler e Christa Steinle, Condición Postmedia è dedicata all'arte contemporanea austriaca, il che limita un po' l'ambito di verifica delle teorie di Weibel; ma ha il pregio di affiancare artisti attivi in ambiti molto diversi, fra cui alcuni giganti della situazione austriaca attuale, come Hans Schabus e Erwin Wurm. Il testo di Weibel, dopo un'argomentazione serrata che prende le mosse addirittura dalla distinzione classica tra “techné” e “epistéme”, si può concedere toni da manifesto che ne rafforzano l'incisività: “L'impatto dei media è universale, e per questa ragione tutta l'arte è già arte postmediale.” E più avanti: “Nessuno può sfuggire ai media. Non c'è più pittura al di fuori o al di là dell'esperienza dei media. Non c'è più scultura al di fuori o al di là dell'esperienza dei media. Non c'è più fotografia al di fuori o al di là dell'esperienza dei media.”

Weibel sostiene che i nuovi media hanno aiutato gli altri strumenti a prendere coscienza di se stessi come “media”, e a indagare il proprio specifico fino a raggiungere l'equivalenza, lo stesso riconoscimento artistico: la fase attuale è invece quella del “missaggio” fra i media, per cui “il video trae vita dal cinema, il cinema dalla letteratura, la scultura dalla fotografia e dal video. E tutti traggono vita dal digitale, dall'innovazione tecnica.” Nessun mezzo domina gli altri: tutti sono pezzi di un unico medium universale, che pone lo spettatore-utente in una condizione nuova, basata sulla partecipazione.

Come tutti i manifesti, il testo adotta toni un po' enfatici. Ma le sue tesi si possono verificare nei lavori in mostra, dalle sculture di luce di Martin Kaar e Peter Kogler, alle immagini ambigue di Jutta Strohmaier e Katarina Matiasek, allo straordinario piano sequenza del video di Muntean & Rosenblum, alle scale cromatiche inserite direttamente nel paesaggio da Michael Schuster.

Ma ancora più importante è che Weibel includa nella sua prospettiva tutta l'arte contemporanea, attribuendo ai media un ruolo decisivo nella sua evoluzione, e superando, nella teoria come nei fatti, quella separazione tra arte contemporanea e sperimentazione mediale di cui, per molti versi, lo stesso ZKM costituisce un retaggio. L'ottimismo di Weibel può sembrare un po' eccessivo dall'Italia, dove il riconoscimento istituzionale e mercantile dei nuovi media è solo agli inizi; ma descrive in maniera convincente una situazione internazionale in cui gli stessi compaiono sempre più spesso nei musei e nelle fiere (come dimostrava, a pochi chilometri dalla mostra, l'edizione di quest'anno di Arco). Speriamo di colmare in fretta il distacco.

NOTE

1. R. Krauss, A Vojage on the North Sea. Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, Thames & Hudson, London 1999. Ed. it. L'arte nell'era postmediale. Marcel Broodthaers, per esempio, Milano, Postmediabooks, 2005

2. F. Guattari, Pour une éthique des médias, in “Le Monde”, 6 novembre 1991

3. Cfr. Adilkno, The World After the Media, s.d., http://aleph-arts.org/epm/eng/aftermedia.html

4. H. Slatter, The post-media operators, s.d., http://aleph-arts.org/epm/eng/operators.html

5. J.L. Brea, La era postmedia. Acción comunicativa, prácticas (post)artísticas y dispositivos neomediales, Centro de Arte de Salamanca / Argumentos 1. Salamanca, 2002. Versione pdf scaricabile dall'indirizzo http://laerapostmedia.net/

6. N. Bourriaud, Postproduction. La culture comme scénario: comment l'art reprogramme le monde contemporain, 2002. Trad. it. Postproduction. Come l'arte riprogramma il mondo, Milano, Postmediabooks 2004

7. P. Weibel, La condición postmedial in AA.VV., Condición Postmedia, catalogo mostra, Centro Cultural Conde Duque, Madrid, 7 febbraio – 16 aprile 2006

-------------------------------------

The Post-Medium Condition

An exhibition at the Centro Conde Duque of Madrid is an occasion to retrace the thinking of our post-media age, from Rosalind Krauss to Peter Weibel

“The message is the message, who cares about the medium”. This boutade, signed 0100101110101101.ORG, could be used as the emblem of an almost finished process that is starting to be labelled as the “post-medium condition”: the passage from an approach based on the use of new media to make art and on the development of the “specificity” of a medium, to another one which takes new media for granted, as fundamental elements of a toolbox that one can readily dip into.

As a matter of fact, the approach lying behind the term “post-media” has a long history: probably longer than the term itself. It is not by chance that Rosalind Krauss1 uses this term in her elegant text from 1999 referring to the 70s that, if on one hand witnessed the outgrowing of Greenberg's approach, on the other hand saw the decline, within the field of video, of reflection on “media specificity”. However, it cannot be denied that, at the beginning of the 90s, the diffusion of the home computer, the internet, of accessible communication devices within everybody's reach caused a revival of McLuhan's theories and the re-emergence of thinking focused on the medium, on its technological characteristics and its implications relating to content. Net Art criticism is particularly full of references to the “specificity of the medium”, a theory that had to be revamped, in a banal fashion, so as to distinguish art that used the Net as a medium from art which exploited it as a mere means of diffusion. At the same time, the first on-line art experiments are distinguished by an approach focused on the medium, by its limits and technical characteristics, not unlike that which urged Nam June Paik to act on the video stream with a magnet.

In a word: if we agree with Rosalind Krauss that the post-medium condition starts with Broodthaers, we have to recognise that it only reached full maturity in the first decade of the century, when the media, its aesthetics and metaphors became part of our reality. It is only when many of us have a device in our pockets that allows us to speak, write, take photographs, shoot a film, listen to music, only when we discover a RFID chip hidden in many book jackets, only when we realise how difficult it is for a week to go by without surfing the internet, or to find non-genetically modified food, can we can declare with certainty that the problem is not how to use media to make art, but on the contrary how to do without it.

From this premise one thing can be understood: what an extraordinary alibi the “post-medium condition” provides to anyone who is interested in taking advantage of the hype that is being created in the artistic field around so-called “New Media Art”. It is logical: if New Media Art is a limited and difficult field to handle, there is not much, today, that cannot be defined as “post-media”. And here, for example, are the theories on painting of the “Google Generation” that seem to re-propose, fifteen years later, the spoof theory of medialism.

To be clear, the possibility of “post-media painting” or the idea of “post-media” itself, is not in doubt. However, I think that such a forceful and intuitive concept needs to be enriched with further levels of meaning, given the risk of it becoming an empty concept before having its due.

The expression “post-media age” was coined by Fèlix Guattari2 at the beginning of the 90s to indicate the age of the new information technologies following on from the mass media. According to Guattari, the new technologies (with the internet at the top of the list) entail a redefinition of the traditional relationship between producer and consumer and the birth of new social practices linked to the media. The expression has had some success in the field of media criticism, which uses it, following Guattari's example, as a synonym for digital media, which supersedes traditional mediation by opposing a decentralized and non-hierarchical (rhizome-like) structure to the old media, allowing diffused use by including and reutilizing the old media3. At the same time, music criticism applies it to the theories of remixing, re-appropriating sounds and instruments and the listener's creative role4. In the artistic field, if on one hand Rosalind Krauss also uses this term with regard to surpassing Greenberg's notion of “medium”, on the other hand the Spanish José Luis Brea5 adopts it in reference to those he calls “web communities of media producers”, who in renewing the avant-garde's ambitions become producers of their very own tools from scratch.

But we should recognise Postproduction6 by Nicolas Bourriaud, although the term “post-media” does not appear, with the merit of giving this theory a qualitative boost. According for Bourriaud, contemporary art, even when it does not use the media, draws inspiration from these latest production models, adopting remixing and postproduction strategies and creating works that are nothing but nodes in a wider information flow. Bourriaud's “post-producer” is no different from Slatter's “post-media operators”; Bourriaud's development consists in taking the entry of contemporary art, even when it seems to have nothing to do with the new media, into the post-media age as a fait accompli.

Or as Peter Weibel says “…the new media were not only a new branch on the tree of art, but have actually transformed the tree of art itself…their intrinsic success resides not so much in the fact that they have developed new forms and possibilities of art, but that they have enabled us to establish new approaches to the old media of art and above all have kept the latter alive by forcing them to undergo a process of radical transformation”7.

With these words the director of the ZKM of Karlsruhe opens the last part of La condición postmedial, a long text introducing the exhibition Condición Postmedia in the catalogue, a show that travelled to the Neue Galerie Gratz and now at the Centro Cultural Conde Duque of Madrid. Condición Postmedia, curated by Elisabeth Fiedler and Christa Steinle, is dedicated to Austrian contemporary art, which limits the scope in verifying Weibel's theories a little; however, it has the merit of putting together artists who are active in very different fields, including some giants of the present Austrian scene, like Hans Schabus and Erwin Wurm. Weibel's text, after a concise argument, even starting from the classic distinction between “techné” and “epistéme”, then allows itself manifesto-like overtones that strengthen its incisiveness: “The impact of the media is universal and for that reason all art is already post-media art”. And further on, “No-one can escape from the media. There is no longer any painting outside and beyond the media experience. There is no longer any sculpture outside and beyond the media experience. There is no longer any photography outside and beyond the media experience”. Weibel believes that the new media have helped the other instruments to become aware of themselves as “media” and to investigate their specificity ultimately achieving equivalence and the same artistic recognition. Instead, the present phase is that of “mixing” media, so that “video lives from films, film lives from literature, and sculpture lives from photography and video. They all live from digital, technical innovations”. No medium dominates the other: all are parts of a universal medium that positions the viewer-user in a new condition based on participation.

Like all manifestos, the text has an emphatic style. But its arguments can be verified through the works on show, from Peter Kogler and Martin Kaar's light sculptures, to Jutta Strohmeier and Katarina Matiasek's ambiguous images, to the singular tracking shot of Muntean/Rosenblum's video, to the chromatic scales that are directly introduced into the landscape by Michael Schuster. But what is more important is that Weibel includes all contemporary art in this perspective, giving to the media a decisive role in its evolution, and overcoming, both in theory and in practice, that separation between contemporary art and media experimentation, of which, in many aspects, ZKM itself represents a legacy. Weibel's optimism might seem a little excessive from Italy's standpoint, where institutional and commercial recognition of new media is only at the beginning; but it convincingly describes an international situation where, more and more often, the new media are appearing in museums and fairs (as this year's Arco, a few kilometres from the exhibition, demonstrated). We hope to close the gap soon.

NOTES

1. R. Krauss, A Vojage on the North Sea. Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, Thames & Hudson, London 1999. Italian edition, L'arte nell'era postmediale. Marcel Broodthaers, per esempio, Milano, Postmediabooks 2005

2. F. Guattari, Pour une éthique des médias, in “Le Monde”, 6th November 1991

3. Cfr. Adilkno, The World After the Media, s.d., <http://aleph-arts.org/epm/eng/aftermedia.htlm>

4. H. Slatter, The post-media operators, s.d., <http://aleph-arts.org/epm/eng/operators.htlm>

5. J.L. Brea, La era postmedia. Acción comunicativa, practicas (post)artstísticas y dispositivos neomediales, Centro de Arte de Salamanca / Argumentos 1. Salamanca, 2002. Pdf version available on line at the e-mail address <http://laerapostmedia.net/>

6. N. Bourriaud, Postproduction. La culture comme scénario : comment l'art reprogramme le monde contemporain, 2002. Italian translation Postproduction. Come l'arte riprogramma il mondo, Milano, Postmediabooks 2004

7. P. Weibel, La condición postmedial in AA.VV., Condición Postmedia, exhibition catalogue, Centro Cultural Conde Duque, Madrid, 7th February - 16th April 2006