From the Sunniest Day to the Darkest Night

dal 21/6/2012 al 7/9/2012

Segnalato da

21/6/2012

From the Sunniest Day to the Darkest Night

Zak / Branicka, Berlin

"Whosoever spends sleepless moments in a bed in Sarajevo might hear the voices of the Sarajevo night" (Ivo Andric). This exhibition focuses on the ties between power, violence, and religion, and draws upon difference as a source of conflict. Works by Maja Bajevic, Adrian Paci, Alban Hajdinaj, Igor Grubic, Hubert CzerepokCzerepok.

curated by Agata Rogoś

“Whosoever spends sleepless moments in a bed in Sarajevo might hear the voices of the Sarajevo night. Hard and firmly strikes the bell at two o’clock in the morning in the Catholic Church. More than one minute passed (exactly seventy-five seconds—I counted) and only then was did I hear the slightly weaker, shrill sound of the Orthodox Church clock, also striking two o’clock in the morning. A moment later the sa-hat-kula spoke in a hoarse, subdued voice from the Bej Mosque, striking the eleventh hour—the ghostly Turkish hour, the strange timekeeping of distant foreign countries. The Jews have no clock, only the heavens know what time it is—whether according to Sephardic custom, or according to Ashkenazi. When all around is still and quiet, the difference separating men equalized by sleep is in the calculation of this hollow phase of the night. When they awake, they will be happy and sad, feast and fast by four different feuding calendars, and all their requests and prayers will be sent to heaven in one of four liturgical languages. The difference is sometimes visible and open, sometimes hidden and treacherous, but it always resembles hatred—this difference is often hatred itself.”

With these words the Bosnian writer and Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andrić described Sarajevo—a town where four religions meet—in his short story entitled A Letter from 1920. Such places never know peace, as the confrontation between various visions of the world more often serve to emphasize differences, and not similarities. Meanwhile, political correctness notwithstanding, the idea of multiculturalism, so deeply rooted in European philosophy, will always remain a pious desire. This exhibition focuses on the ties between power, violence, and religion, and draws upon difference as a source of conflict: “The difference is sometimes visible and open, sometimes hidden and treacherous, but it always resembles hatred – this difference is often hatred itself.”

Is it possible, then, that in such places paradise and hell, day and night, and the sacred and the profane live under the same roof? If so, small wonder that the Iranian film director and poet Abbas Kiarostami wrote the following on the relationship between good and evil, and beauty and violence: "I have safely journeyed a thousand times from the sunniest day to the darkest night." The title of the exhibition derives from this quote.

Watching Maja Bajević’s video (Double Bubble, 2001), we are uncertain at first what culture or faith the artist’s words refer to: “When I go to church, I always leave my machine gun by the door. (…) I go to church, I rape women.” Reading statements by men, Bajević analyzes the ties between religious ethics and the dual morality toward the position of women and violence.

Adrian Paci’s film (PilgrIMAGE, video, 2005) draws from the 15th-century history of the magical “transfer” of a painting—a relic of the Mother of God from Albania’s Shkodër (the largest enclave of Catholicism in Albania) to the Italian town of Genazzano. Paci has decided to reverse the course of history and restore the lost picture to the Albanians. He organized a public projection of the picture in Shkodër, while simultaneously projecting a film of Shkodër’s praying inhabitants in the church in Genazzano. In this way he literally transfers the sacred space to the sphere of the profane, and vice versa.

The two remarkably sensual photographs by Alban Hajdinaj (June in Albanian Means Month of Cherries, 2002) suggest more than they say outright. Dread and disquiet lurk beneath these pictures evoking Dutch still lifes. Is the main figure in the pictures dead, or has he dozed off after some revelry? Are the red stains on his shirt cherry juice, or his blood?

Igor Grubić’s work (Angels with Dirty Faces, photographs & video, 2006) is a documentary piece, pertaining to the miners’ protest at the Kolubara (КОЛУБАРА) mine in Serbia; these protests were instrumental in bringing about the overthrow of Slobodan Miloљević’s regime.

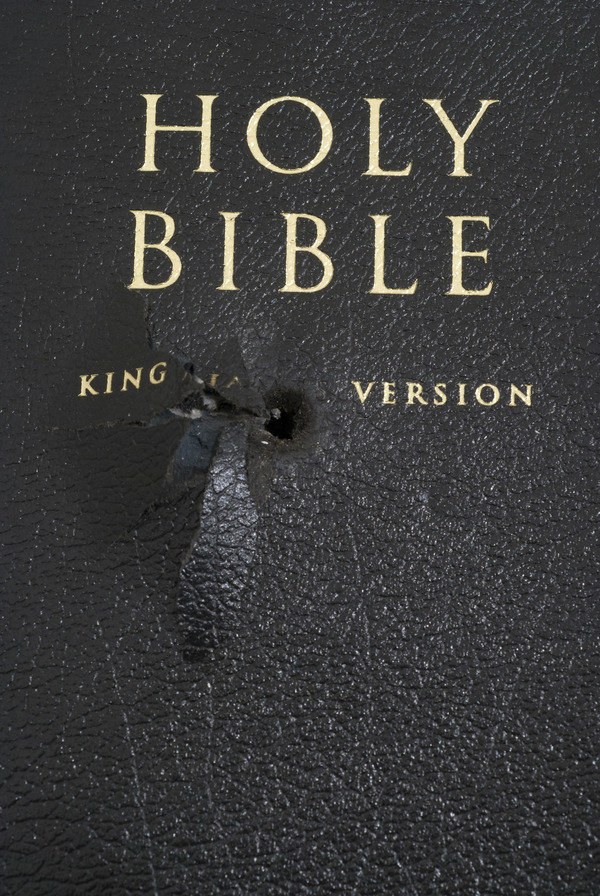

Hubert Czerepok’s work (Salvation Islands, installation, 2009) consists of three bullet-riddled piles of holy books: the Bible, Koran and Tanakh. This work concerns issues tied to the politicization of the sphere of the sacred: here the bullets falls—literally and figuratively—between the pages of history. The artist alludes to stories of cases where holy books hidden in the pocket of a uniform have saved soldiers from being shot. As such, religion is both a source of violence and a form of protection from evil.

Image: Hubert Czerepok, Salvation Islands, 2009, detail | Object, 3 piles of books, gun bullets, approx. 50 x 35 x 35 cm each

Opening June 22, 2012, 6 to 9 pm

ZAK | BRANICKA

Lindenstr. 35, 10969 Berlin

Tue-Sat 11am-6pm