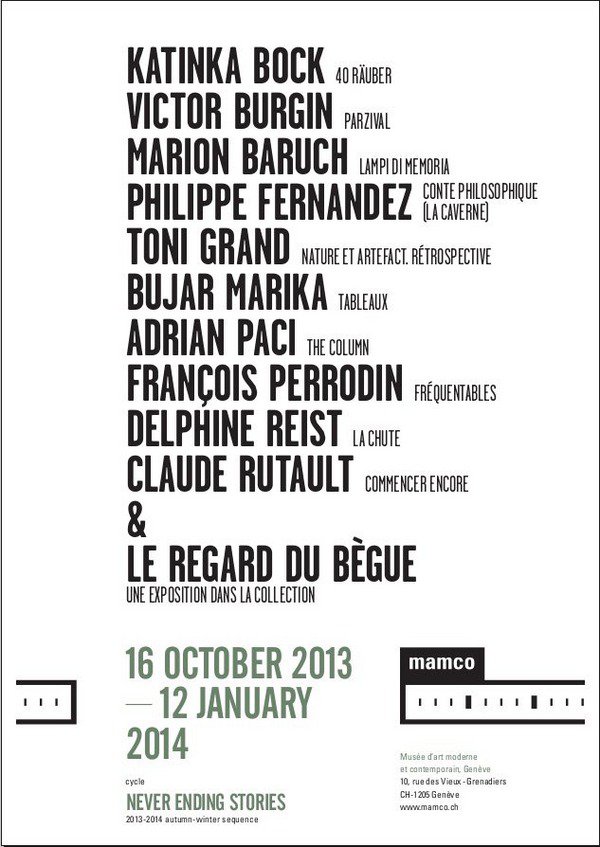

Katinka Bock

Victor Burgin

Marion Baruch

Philippe Fernandez

Toni Grand

Bujar Marika

Adrian Paci

Francois Perrodin

Delphine Reist

Claude Rutault

14/10/2013

The never ending stories

Mamco, Geneve

These stories are the ever unique accounts of Mamco's relationships with the artists who come here, or return here, to show us how their work has been progressing. The exhibition "The stutterer's gaze: physics of memory" provides a subjective sweep of the collection on display at the museum.

Mamco’s autumn-winter 2013-2014 sequence is the start of a

new cycle entitled The never ending stories. This may refer

to the more enduring status of our museum, now officially

acknowledged as being of ‘strategic importance’ to the Canton of Geneva. Yet these endless stories may also suggest the

administrative complications associated with reaching

adulthood – whether the ‘adult’ in question is a person or a

museum. And, above all, these stories are the ever unique

accounts of Mamco’s relationships with the artists who

come here, or return here, to show us how their work has

been progressing.

The fourth-floor exhibition Le regard du bègue: physique du

souvenir (‘The stutterer’s gaze: physics of memory’), following on from last spring’s Partage de minuit (‘Midnight sharing’), provides a subjective sweep of the collection on display

at the museum. The works are in dialogue with one another,

weaving together the threads of dreams, melancholy and burlesque.

Delphine Reist

On entering the Don Judd Loft, visitors will no doubt have a

frustrating sense of having got there too late, when it’s all over,

and seeing nothing but the remnants, the ruins of a spectacular, violent performance which Delphine Reist, who lives and

works in Geneva, has called La Chute (‘The Fall’). On the floor

is a large piece of ceiling that has just come down, exposing

its metal skeleton. A little further on, another destructive

force, another effect of the laws of gravity can be seen in a

large wine stain on the wall together with bits of broken bottle, the result and the cause of a movement halfway between

a drunken brawl and the polished ritual of a christening. For

her first exhibition at Mamco, Reist presents an installation

that is full of nods to history (that of the various avant-gardes

as well as the fall that is such a key part of Christian iconography) and profoundly transforms one of the museum’s main

spaces.

Marion Baruch

After moving from Hungary to Italy in the 1950s, Marion

Baruch based her artistic work on the then flourishing textile

industry in the northern region of Lombardy. Her sole material was scraps of fabric, which she chose ceremoniously, dis-

playing them in metaphorical portraits and making them grow

on the wall as though they were trees. Born in 1929 and

marked by the tragic events of the century, Baruch includes

a major social dimension in her work. Her fondness for textiles, of which she only uses remnants, suggests a restles bleconsumerism. At the same time, her minimal interventions, remote as they are from ‘women’s work’, can also be read as

a scathing commentary on the working conditions of the nimfingered seamstresses (sometimes known as petites mains,

or ‘small hands’) who are employed in haute couture. Now

blind, Marion Baruch continues to work with her fingertips

and her memories – as reflected in the title of her exhibition

at Mamco, Lampi di memoria (‘Flashes of memory’).

François Perrodin

In an exhibition covering three decades of his work, François

Perrodin presents paintings that are fréquentables (approachable) despite their austerity. His works are entirely grey, simply playing with the shadows of a minimalist chiaroscuro, the

geometric relationships between length, width and thickness,

the contrasts between matt and shining elements, and the

way the paintings are hung. This work is thus completely at

home in the Cabinet des abstraits, where it rekindles the mem-

ory of concrete art and minimalism. Yet Perrodin’s work is

more than just formal, or formalistic, research, for what matters most is the viewer’s relationship to the work. The title of

his exhibition thus asserts the need for connection as a way

for painting to exist.

Toni Grand

The entire second floor of Mamco presents a retrospective of

work by Toni Grand (1935-2005). Initially close to the Supports/

Surfaces movement, the French sculptor was more interested in the uses of materials than in their specific qualities. His

work therefore focused on acts, such as splitting or assembling, rather than material or surface effects. Exploring the

ways in which artists work with materials, he made his own

reassessment of the Supports/Surfaces movement’s analysis

of artistic resources. The Nature and artefact exhibition

reviews the various stages of Grand’s work, from his wooden

sculptures in the 1970s to his later pieces that included features alien to the world of sculpture, such as a goods lift, or

stuffed eels.

Philippe Fernandez

Ever since the late 1990s, Philippe Fernandez has made art-house-type films (so far four short and medium-length ones

and one long one) which are usually shown in cinemas. His

world, often described by critics as philosophical and burlesque, displays a striking visual coherence and a strange

temporality which often makes us feel we are elsewhere,

although everything he films seems realistic if not actually

real. Fernandez’s first opus, produced in 1998 and entitled Philosophical tale (the cave), is no exception. Displayed on the

second floor, this is a parable inspired by the myth of the cave

in Book VII of Plato’s The Republic, on the pursuit of lucidity

in a shadowy, make-believe world. In presenting this work,

Mamco is pursuing its exploration of the current role of cinema in exhibition spaces.

Katinka Bock

For her first exhibition at Mamco, the German artist Katinka

Bock has treated the Plateau des sculptures as a landscape

painting. Landscapes, she says, are not nature, but always a

way of seeing nature. Yet she wants to offer viewers an over-all view so that they can then get lost in the details – all of

which are sculptures, by no means symbolic or illustrative, for

the raw materials in this work are used for what they are rather than for their symbolism (a lemon is a lemon, not a sun). We

should also note that the space assigned to Katinka Bock’s

exhibition suggests to her a public place in which each feature is very precisely arranged – a place where citIizens walk.

Although the works are often produced with the help of calculation, they are also like notes of music on a staff. An acceleration or a regular beat is all that is needed for viewers to

compose their own music, just as they would construct a sentence. Terracotta sculptures, and use of natural elements

such as rain, are also recurring features of a sculptural vocabulary that is amply and richly reflected in Bock’s 40 Räuber

(‘40 thieves’) exhibition.

Victor Burgin

Parzival is a filmic reverie, based not exactly on the Wagner

opera but on a particular moment in the composer’s life. In a

very personal way, Burgin attempts to recapture Wagner’s

sojourn in Venice from 1858 to 1859. During this period, having stopped working on The Ring of the Nibelung, he finished

Act II of Tristan and Isolde. But his thoughts were already

drifting towards Parzival. He had read the mediaeval epic

poem long before, and it would be another twenty years

before he turned it into an opera. What interests Victor Burgin

is the point at which, in Wagner’s mind, the topic was no longer just a poem but was not yet an opera. It was an object of

thought, of daydreams, with the musician’s daily, personal or

political ideas clinging to them. What Burgin is thus seeking

is this hazy, in-between Parzival – and his film is the luminous

trace of his encounter with Wagner.

Adrian Paci

Presented in the collective exhibition “Isola (Art) Project

Milano” in 2003, Adrian Paci offers his latest works, The Column, projected on the first floor. Born in Albania but based in

Milan since the late 1990s, Paci has produced a wide range

of different work (paintings, photographs, videos, sculptures

and installations) in which the moving image plays a prominent part and the question of movement likewise predominates. ‘Being at the crossroads, at the boundary between two

separate identities, is a part of all my film productions’, he

says. And indeed his half-hour film The Column explores and

exhibits the time of movement – geographical movement, but

also the movement of a historically ancient architectural form,

treated here as a metaphor for the present-day human condition. A work of outstanding visual beauty, The Column is also

a voyage through memory.

Bujar Marika

While pursuing the scientific training that led him to be a

teacher, an editor of the Albanian journal Shkenca dhe Jeta

(‘Science and Life’) and above all an internationally renowned

designer, Bujar Marika – who was born in Tirana in 1943 and

died in Geneva in 2009 – was always greatly attracted to art

and architecture. But it was not until the age of 52 that he

embarked on his career as a visual artist. His work, which has

been regularly exhibited at Mamco and is part of the museum’s collection, revolves around the basic features identified

by the artist as ‘forms, colours, technique, frontality and immediacy’. These features recur in all his paintings on display this

autumn – paintings whose economy of form, neutral and

impersonal treatment of the surface and minimalist approach

are the predominant features of a remarkable, and in many

ways unclassifiable, body of work.

Claude Rutault

The four rooms of the Suite genevoise display the latest stage

of Claude Rutault’s painting. The artist’s ‘inventory’, updated

once more for this new exhibition, has been a permanent feature of Mamco ever since the museum first opened. Rutault is

well known for painting in the same colour as the walls his

paintings will be hung on. With this initial constraint, he works

in the form of statements he calls ‘definitions/methods’ whose

visual production is supervised by private or institutional collectors. Claude Rutault’s exhibition Commencer encore (‘Starting again’, or ‘Still starting’) presents four stages of his work

– painting, not painting, repainting and depainting – which

describe not only the main periods of his career but also, as

the artist says, all the possibilities of painting.

Press contact:

Sophie Eigenmann T. +41 223206122 s.eigenmann@mamco.ch

Press conference, Tuesday 15 October at 11 a.m.; show opening starting at 6 p.m.

Mamco Musée d’art moderne et contemporain

Rue des Vieux-Grenadiers 10 1205 Geneva Switzerland

The museum is open Tuesday through Friday from noon to 6 p.m., the first Wednesday of the month until 9 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed the Mondays and Tuesday 24, Wednesday 25, Tuesday 31 December 2013 and Wednesday 1st January 2014.

Entrance:

Regular admission CHF 8.–

Reduced admission CHF 6.–

Group admission CHF 4.–