Philippe Thomas

Franck Scurti

Allan McCollum

Marijke van Warmerdam

Christopher Williams

Ulla von Brandenburg

John M. Armleder

Philippe Parreno

Dennis Oppenheim

10/2/2014

Des histoires sans fin

Mamco, Geneve

Six new exhibitions in a rich variety of sizes: the retrospective by Philippe Thomas and Franck Scurti's works; on show five monographic exhibitions with a large selection of works from the museum's collection, including John M. Armleder, Philippe Parreno and Dennis Oppenheim.

The spring sequence in the never ending stories cycle, which

will be held from 11 February to 18 May 2014, presents six

new exhibitions in a rich variety of sizes. For example, the

retrospective of work by the French artist Philippe Thomas

(1951-1995) can be seen on all four floors of the museum,

whereas Franck Scurti’s work will be on display in two

rooms on the third floor. Besides the five monographic exhibitions, a large selection of works from the museum’s collection (including John M. Armleder, Philippe Parreno and Dennis Oppenheim) which have seldom been exhibited in recent

years, and all deal with flatness, will be exhibited on the Plateau des sculptures.

Homage to Philippe Thomas and other works, including The

Shadow of the Waxwing (after Pale Fires)

Mamco presents a retrospective of work by the French artist

Philippe Thomas (1951-1995), some of whose work is part of

the museum collection. Displayed on all four floors of the

building, it is divided into three sequences.

L’Ombre du jaseur (d’après Feux Pâles) (‘The Shadow of the

Waxwing (after Pale Fires))’ can be seen on the fourth floor.

In 1990, CAPC (the Bordeaux Museum of Contemporary Art)

invited Philippe Thomas to design the Pale Fires exhibition.

Through his agency les ready-made appartiennent à tout

le monde®, Thomas saw the invitation from the museum as

an opportunity to raise what he called ‘fictionalism’, the principle of fiction applied in his previous work, to the level of the

institution, a neutral place of scientific knowledge that is not

usually suspected of partiality. The Shadow of the Waxwing

presented here is not a literal replica of the exhibition Pale

fires – an exercise that would be bound to fail today – but is

designed as an exhibition in the shadow of the first one.

In December 1987, at New York’s Cable Gallery, Philippe

Thomas opened his first agency, which he called ready-

mades belong to everyone®. Soon afterwards, in September 1988, a second branch was established at the Claire Burrus gallery in Paris, with the equivalent French name les

ready-made appartiennent à tout le monde®. Thomas

thereby gave a radical new direction to artistic work by thoroughly reappraising the artist’s role and place in the creative

process and providing art not only with new tools but also with

new areas of research. Most of what was produced by the

agency is displayed on the second and third floors at Mamco,

where we can see the author fading into the background to

make way for numerous other names and signatures.

Finally, a set of works produced by Thomas between 1981 and

1987 is presented in the Camera Candida on the first floor. This

fictionalist period heralded the main principles that the artist

was subsequently to apply in his agency les ready-made

appartiennent à tout le monde®. Consisting of numerous

writings and some pictures, this first period unfolds in the aesthetic and rhetorical setting of the clue, the proof, the ‘piece

of evidence’.

Franck Scurti: The Brown Concept & New Lights from

Nowhere

Since the early 1990s the French artist Franck Scurti has been

guided by a constant concern to shift the usual meanings and

morphologies of forms. For his first exhibition at Mamco, in

two rooms on the third floor, he has designed a two-part

series of works most of which were produced in the past two

years and are presented as a collection within the museum

collection. The Brown Concept and Nouvelles lumières de

nulle part (‘New lights from nowhere’) consist of some thirty

works linked by associations of form, process or concept.

Most have never been on display before; some have been produced specially for the exhibition. The starting point for this

constellation is the artist’s view of the physical world, of the

objects that he comes across and that provide him with material for continuous creation. The title The Brown Concept is

taken from the name of the British botanist Robert Brown,

who in the nineteenth century discovered that all particles of

matter are subject to the incessant movement now known as

‘Brownian motion’. A presentation marked by a momentum of

interconnected forms and ideas.

Marijke van Warmerdam: Light

Marijke van Warmerdam’s films (which are always silent) are

endless loops. Born in 1959, the Dutch artist has specialised

in treating her films as paintings, storyless and timeless. But

whereas the painting is a window on the world – a doxa of art

history ever since the Renaissance –, Van Warmerdam’s 2010

film Light simply shows a Venetian blind that conceals a win-

dow, with dazzling light breaking through its rustling sounds.

One could see this as a Dutch minimalist film. Like constructivist paintings, which deconstructed painting into fundamen-

tal components, Van Warmerdam’s loop replays the resources and issues of film: shadow, light and the hidden gaze. This

game of hide-and-seek (if one may call it that) corresponds in

this sequence of exhibitions to the disappearance strategy

adopted by Philippe Thomas as well as the works of Christopher Williams – evoking, without any narrative, the game

played by artists who conceal themselves, behind an official

body or reproduction technology.

Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness

At first – and even second – glance, Christopher Williams’s

photographs are disconcerting. How are we to interpret these

extraordinarily sharp pictures of coldly banal objects? Born

in 1956, the American artist is a successor to Bernd and Hilla

Becher, whose chair he holds at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. But rather than simply record reality, he fills up his

pictures with discreet allusions that revisit the history of

industrial society. The inordinately long titles are codes to be

deciphered. The actual objects are more symbolic than they

may at first seem – for instance, the fake corn cobs, a reference to America’s leading cereal resource whose derivative

products can be found everywhere, including in photographers’ films. And so the viewer should stop for a while to

dream and reflect about what these pictures – of which, purposely, only a very small number are put on display – actually mean. The Production Line of Happiness (the title of this

exhibition, which forms an accompaniment to the artist’s

major retrospectives in Chicago and at New York’s MoMa in

2014) relentlessly recounts the dream of Western society, its

efficiency and its perception of the world – a dream shaped

by its own propaganda tools: the clean, glamorised ‘realism’

of advertising images.

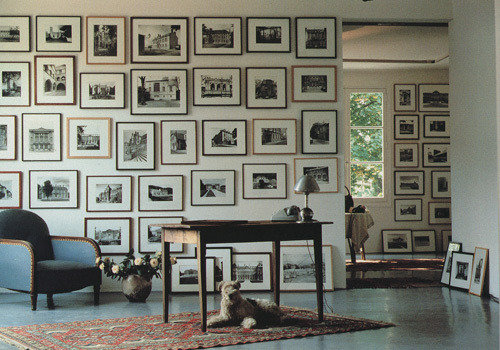

Allan McCollum: Again

The anthropologist and moralist Allan McCollum unpicks the

assumptions that structure our behaviour as viewers. His

work may be seen as a criticism of ways of approaching and

receiving art. He questions all our rituals and habits in relation to art. Having set out in the late 1970s to criticise the sacrosanct notion of originality, the American artist, who was

born in 1944, erases the usual boundaries between industrial, craft and artistic production. He prefers the multiple to the

singular, and infinite repetition to the inspired gesture. This

can be seen in the exhibition Encore (Again), which includes

his Surrogate paintings (1979) and his Glossies. The Surrogate

paintings were made out of wood or thick cardboard by craft

methods. The small, black monochrome paintings were first

presented in a conventional manner. McCollum’s intention

was then to create a surrogate, a ‘model, a standard sign-for-

a-painting which might represent nothing more than the identity of painting in the world of other objects.’ In 1981 his Surrogate paintings were succeeded by the Glossies, whose

rectangular surfaces were coated by hand with Indian ink and

then covered with a transparent sheet of adhesive plastic.

This time Allan McCollum was attempting to produce surrogates of photographs from which all trace of an image had

disappeared. Other works of his can also be seen in the first-

floor rooms, which present the artist’s subtle, prolix challenge

to the false assumptions of the art world and the objects in it.

Flatland

Flatland is the title of a work of fiction written in the late nineteenth century by the British author Edwin A. Abbott. It

describes a flat world in which all shapes and figures are flattened, two-dimensional and enclosed in a very limited vision

and perception of the world. This satirical work, an allegory

of Victorian society in all its rigidness, was much read by

members of the early-twentieth-century avant-garde, who

were themselves preoccupied with the fourth dimension. But

there is nothing limited about the flat sculptures exhibited on

the Plateau des sculptures. On the contrary, they show the

fertility of flatness, of ‘platitude’, in the art of the past thirty

years. What they have in common is that they dispense with

pedestals, a traditional attribute of sculpture, and explore the

horizontality of space. Thus Philippe Parreno’s sea – a lightly, regularly folded blue blanket laid on the floor, displaying

wavelets and entitled C’était la mer (‘It was the sea’, 1992) –

is exhibited next to a sandstone floor work by Katinka Bock,

One Meter Sculpture (2013). Stéphane Steiner’s ground construction and Sergio Verastegui’s inserts, shown for the first

time at Mamco, appear next to a work by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster (twelve perforated sections of red carpet that are

joined up as a book). But Flatland also includes a number of

works that rise up into space from the floor they lie on, such

as Bernar Venet’s pile of coal. Also on display is a vast array

of sculptures by almost fifteen artists who make horizontality

the very condition whereby the works take shape.

Opening Tuesday February 11th 2014

Mamco

rue des Vieux Grenadiers 10, Geneve

Opening hours: from Tuesday to Friday 12 - 18 and Saturday and Sunday 11 - 18

Admission: 8CHF and reduced ticket 6 CHF