Two Exhibitions

dal 20/11/2014 al 24/1/2015

Segnalato da

20/11/2014

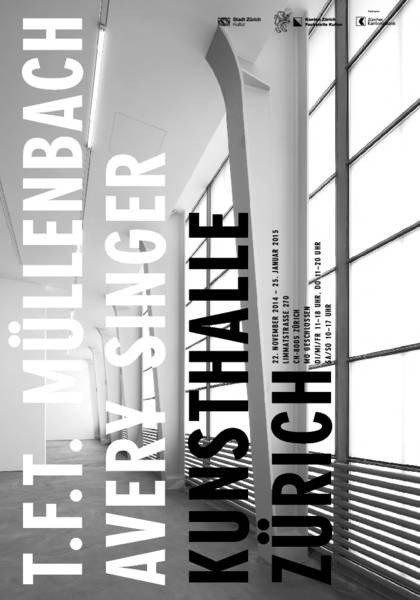

Two Exhibitions

Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich

Thomas Mullenbach. The exhibition presents the first comprehensive overview of paintings and drawings with a focus on works created specially for this show. 'Avery Singer: Pictures Punish Words' the exhibition presents the technically and iconographically striking paintings of the artist.

Thomas Müllenbach

Thomas Müllenbach (born in Koblenz, Germany in 1949, lives and works in Zurich) turns our

everyday perception of familiar things on its head, and subverts the collective

understanding of the sense, purpose and value of the visible. These shifts in the everyday

are the focus of his attention. In the process, he also repeatedly scrutinises the history of art

and explores the possibilities of painting. The exhibition in Kunsthalle Zürich presents the

first comprehensive overview of Thomas Müllenbach’s paintings and drawings with a focus

on works created specially for this show and recent works, complemented by a selection of

earlier works.

Thomas Müllenbach’s interest is constantly aroused by the normal and familiar – be it a jug, a

bunch of flowers, a flat screen monitor, the numerous exhibition flyers sent to him, a bank lobby or

a bedroom. He does not merely reproduce these things and their surfaces in these works, but

captures the everyday, almost imperceptible shifts associated with them and the accompanying

moments of irritation. These are the motifs that refuse to leave him alone. When selecting details

from images, he omits the apparently important element only to refer to it through a supposedly

unimportant one. With his images, the artist presents the viewer with fragments, in which he

refuses to follow the traditional conventions of representation, allows the edges of the image to

crop heads and objects, and mixes different perspectives in one work so that the viewers can

discover the unknown in the familiar, and the familiar is transformed into something uncanny.

The drawing assumes an independent place in Müllenbach‘s œuvre and offers practically unlimited

scope for experimentation. A group of large-format works revolves around places in which state-of-

the-art technology is used – and frequently also fails. Illustrations from the daily press and

specialist publications, from which he reproduces a detail provide the template for these works.

Strong graphite lines outline cables, tubes, control panels and complex structures, uniting chaos

and functionality and drawing the viewer into the world of high technology. Tschernobyl 1 (2004)

symbolically presents one of the rooms in the eponymous nuclear power plant and thereby refers to

the nuclear disaster of 1986, which resulted in the explosion of the reactor through the exposure

and ignition of the reactor’s graphite moderator. A connection is established here between the

hazardous nature of the material used in the reactor and the drawing medium graphite. The

ominous occupation of space also plays a role in the works 3 x door to NSA (2014). Müllenbach does

not provide a view into an office at the American security authority, but instead shows the closed

office door, thereby conveying the importance of the location through a simple, trivial object – the

door. The economic and currency graphs which Müllenbach quotes in the work DAX, 26.9.97 (1997)

are also something we encounter day in, day out. The artist depicts the course of the German share

index in a large-format painting and presents the graph on a green-yellow background, prompting

interaction between abstraction and figuration.

In the series of works entitled Halboriginale (‘half-originals’) (2005–2013) Müllenbach transposes

the numerous invitations he has received to exhibition and art events since 2005 as objects

representative of the ‘everyday life’ of the art world into works of his own. The watercolours, which

are presented in a comprehensive space-encompassing installation, reflect their models in their size

and motifs: ranging from Dürer to van Gogh, from national to international artists and from

figurative subjects to abstract fields of colour, these works play with the idea of recognisability.

Müllenbach’s ‘half-originals’ are neither plagiarised nor copied, they involve the individual

interpretation of technical reproductions of works of art to form new works.The small-format series Xenakis (2012) centres on the Greek composer and architect Iannis Xenakis

(1922 – 2001). Müllenbach does not focus on the visualisation of Xenakis’s musical work, however,

but on his photographic portraits, in which the left side of the composer’s face was always

concealed by shadows or turned away from the camera – a personal decision by Xenakis, whose

face disfigured by a grenade in a street fight in 1945. Müllenbach reconstructs this hidden half of

the face with fine pencil strokes as a careful approximation for public presentation.

Although there is no stylistic correlation between Müllenbach’s works on paper and paintings,

there is in terms of content: they all revolve around the normality of the everyday and refer to time

as a quality that can be provided by prolonged lingering and the boredom of the everyday. Space is

provided for Müllenbach’s paintings in the recently built additional floor of the Kunsthalle Zürich.

Whereas, in the past, the artist applied motifs to wide-ranging supports using expressive and

sometimes pastose brushstrokes, his more recent works are based on a reduced pallet and are

characterised by the thinner application of the paint. This work is consistently pervaded by the

exploration of interior and exterior space. In his Wall series, Müllenbach transfers the exterior to

the interior and introduces the brick façade of the Kunsthalle’s Löwenbräu building and dry-stone

walls into the museum space on large-format oil paintings. His depictions of interior spaces, be

they private or public, are borne by an aesthetic of the inconspicuous presenting familiar objects in

their original environment – they depict an armchair, a bed, the artist’s parental home and the

standard lobbies of banks and insurance companies. The banking hall in Pictet (2007) and the view

into the hotel lobby in Hotelhalle (2007) show places free of all decorative embellishments. By

voiding them in this way, Müllenbach reveals the architectural structure and allows the intrinsic

function of each space to emerge clearly.

Müllenbach repeatedly engages in a highly individual dialogue with the history of art. Most

recently, he explored the dumbness of electronic media like monitors – and, hence also, Kasimir

Malevich’s black square, the iconic work of the zero point of painting. If the black surfaces of the

switched-off screens in our homes, of display boards and bearers of information in the reception

area of the Kunsthalle Zürich do not immediately remind us of Malevich’s square, they do when

translated into painting. In contrast to Malevich, who established Suprematism in 1915 with the

painting Black Square, Müllenbach depicts the black squares in their spatial environment and

returns them to the realm of figurative painting. In more recent works, Müllenbach adopts the

theme of the non-finito, the unfinished work. In these works he presents blank white figures

against a developed background and thus links to a visual tradition of Henri Matisse and Paul

Cezanne. These “reversed figures”, as the artist calls them, populate their environment like ghosts

and provide a space for projection by the viewer.

----

Avery Singer

«PICTURES PUNISH WORDS»

The technically and iconographically striking paintings of Avery Singer (born in 1987, lives

and works in New York) thwart our visual expectations. At an initial glance, they resist a

clear classification of painting or printing processes. Hence her works raise the obvious and

artistically pressing question of how the digital information that surrounds us can

materialize itself – be it as a flat image on paper or more recently in 3-D in plastic, or on and

in every other possible material surface. Avery Singer has created a cycle of works

specifically for this first institutional solo exhibition. Following its presentation in Zurich,

the exhibition will be shown at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin

(12 February – 12 April 2015).

While the analysis of painting has been an ongoing concern for Avery Singer since 2010, she also

experiments and explores imaging processes. Her motifs are inspired by the seemingly infinite

flood of images on the Internet. She also processes everyday occurrences and realities in her

paintings and repeatedly finds inspiration in literature. With the help of the graphic program

SketchUp, which is used for 3-D modeling in architecture, Avery Singer constructs complex spatial

compositions filled with abstracted figures and objects. In the course of this process, the motifs are

translated into geometric forms and reduced to simple elements: hair becomes zigzag lines,

eyebrows straighten, arms turn into blocks and the female bosom becomes an asymmetrical

polygonal outgrowth of the body. Singer projects these computer-generated sketches onto a canvas

or panel, separating the forms from each other using masking tape and creating surfaces on the

canvas in a grey palette with airbrush. Through their rejection of color, these works follow the

tradition of Grisaille – a style of painting that featured predominantly in medieval panel painting

and the Renaissance, and was frequently used for the translation of sculptures into painting. The

airbrush technique heightens the planarity of the painting surface to an extreme and contrasts

with the illusionistic spatiality of the image compositions, an approach that broaches and further

develops questions relating to art history and perception. As trompe-l’oeils, the large-format works

open up spaces that invite the viewer to walk into them, or at least risk a look behind the canvas to

see whether another space lies behind it. The planarity of the canvas is also ruptured by the form

of the presentation: By allowing the paintings to float freely in the space on delicate metal cables,

rather than opting for the traditional wall hanging, the artist creates a spatial constellation in the

exhibition by using the paintings themselves.

Both the physical characteristics and themes of Singer’s paintings always refer to the history of art

and their own emergence, that is the stories and problems associated with the creation of art or

images. Allusions to the motifs and styles of classic modernism and to post-modernist debates can

be identified in her works. The question is also raised as to the impact of the shifts in meaning

resulting from the conditions of digitality and virtuality on the artistic sphere today and,

particularly also, the medium of painting. The insignias of the “fine arts” collide with avant-garde

tropes, and parodic-autobiographical motifs constantly allude to clichés of the art world. Adopting a

humorous tone, Avery Singer demonstrates rituals and social patterns and presents stereotypes of

the artist, curator, collector and writer. In this context, she adopts the historical loci of art

production– the studio, the art college and the institutional space – where the myth of the artist

and cult of genius are fostered: How are artists made? How is art made?

The group of people in the work Happening (2014) are trapped in the act of art production. The

snapshot presented in this work is inspired by documentary photographs, which Singer regularly

encounters in her research on performance art, and evokes the happenings of the 1960s. The work

entitled Director (2014) also refers to artistic activity. It is a portrait of a recorder player who can be

interpreted as an artist or, as indicated by the title, a director. The musical instrument, which tends

to be played by children, allows the figure to become an entertainer and is reminiscent of themusician at the royal court, or even the court jester. As Avery Singer points out, the painting also

refers to the idea of awareness as an internal model constructed by the brain. Just like the Pied

Piper of Hamelin, whose music seduced the children to follow him, we, as art viewers, may

surrender our selves to the seduction of the recorder player presented in this painting.

In the painting Gerty MacDowell’s Playbook (2014) Avery Singer links Vito Acconci’s performance

piece Seedbed (1972) with a scene from James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). The work shows a kneeling

woman on a table-like structure, who is bending forward with one leg and arm raised. In the space

below her, we see another figure, whose gaze is directed at the viewer and is masturbating. The

presentation relates to a scene in Joyce’s novel, in which the protagonist, Leopold Bloom,

masturbates on the beach while Gerty MacDowell, who is sunbathing, exposes her underwear to

him. The structure on which the two figures are presented also refers to the double wooden floor

which Acconci built for the performance piece Seedbed at the Sonnabend Gallery in 1972 where he

lay hidden underneath a ramp, masturbating to and fantasizing about the visitors walking above

him. The avant-garde literary and art-history settings of these temporally and spatially removed –

and seemingly unrelated – works are linked to form a new image through the theme of male

masturbation.

Press Information

T +41 (0) 44 272 15 15 / presse@kunsthallezurich.ch

Opening: friday, 21 november, 6-9 pm

Kunsthalle Zürich

Limmatstrasse 270 CH-8005 Zürich

Hours

TUE/WED/FRI 11 AM–6 PM, THUR 11 AM–8 PM, SAT/SUN 10 AM–5 PM, MO CLOSED

Adults CHF 12

Reduced CHF 8.00