Jesus Rafael Soto

dal 14/1/2015 al 14/2/2015

Segnalato da

Adam Abdalla - Nadine Johnson & Associates

14/1/2015

Jesus Rafael Soto

Galerie Perrotin, New York

'Chronochrome'. The exhibition presents some sixty works from his estate or from institutions, made between 1957 and 2003. The term chronochrome is used less in its original sense than to describe the kinetic exploration of the monochrome.

curated by Matthieu Poirier

Galerie Perrotin presents “Chronochrome,” a double exhibition

dedicated to Jesús Rafael Soto (1923-2005), held simultaneously

in its Paris and New York spaces. Organised in collaboration with

the artist’s estate and curated by Matthieu Poirier, the exhibition will

present some sixty works from his estate or from institutions, made

between 1957 and 2003. This two-part exhibition continues the

current international rediscovery of Soto, which is illustrated by the

recent retrospective at the Musée National d’Art Moderne - Centre

Pompidou (2013), and by his inclusion in “Dynamo. A Century of

Light and Movement in Art. 1913-2013” at Galeries Nationales du

Grand Palais (2013), as well as in the current “ZERO: Countdown

to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s” at the Guggenheim Museum in New

York, in the Frank Lloyd Wright building where Soto had a major

retrospective back in 1974.

For Soto, colour is experienced in and for itself only in the real time

and space of perception. The term “chronochrome” is used less in

its original sense (it was a process for making colour films, invented

in 1912) than to describe the kinetic exploration of the monochrome.

Soto was a close friend of Yves Klein, but in Soto’s work, pure

colour leaves the stable support of the surface in order to become a

vibratory phenomenon.

Jesús Rafael Soto was born in Venezuela in 1923. He trained at

art school in Caracas and came to Paris in 1950, which remained

his base for the rest of his life. His work developed gradually from

his first Parisian pieces, created partly under the influence of the

Neoplasticism of Piet Mondrian and the theories of Laszló Moholy-

Nagy on light and transparency in his writings Vision in Motion.

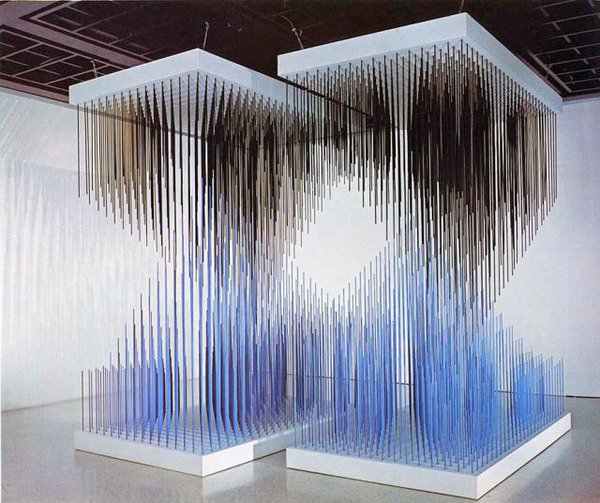

In the 1950s he conceived his first “optical vibrations,” the

constituting principle that would remain active in almost all his future

work: a play of grids on two distinct levels, a few centimetres apart.

The first of these levels is irregular and transparent and constituted

by either silkscreened motifs or painted rods, and the second,

behind it, has fine painted vertical lines in black and white. This

relation between foreground and background is crucial: visually,

it generates an undulating, changing effect (moiré) every time the

beholder’s viewpoint shifts, even if just a little. From then on, Soto

abandoned two-dimensional painting in favour of these “reliefs” in

which that interstice between the two layers plays such an important

role, and for sculptural pieces in which a “rain” of coloured rods or

threads create a complex immaterial effect that contrasts with the

simplicity of the material elements, just as the rhythmic mobility of

the vibration belies the neutrality of the colour.

The properties of the work thus vary with the angle from which

it is viewed, creating a motor effect in the observer and integrating

the elasticity of perception. This dynamic quality was often

misunderstood in Soto’s early work, as it was in the art of Heinz Mack

and Bridget Riley. Soto was alternatively heralded as the hero of

“kinetic art” or “op art”—a status he regularly rejected as he sought

to establish his singularity. Even if he declined the invitation to feature

in “The Responsive Eye” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in

1965 because of what he saw as an excessive prominence given

to Victor Vasarely and his purely “optical” paintings, his approach

nevertheless fits within the context of what the show’s curator,

William Seitz, termed “perceptual abstraction”: a new kind of

art rather based on phenomenology, which made spatio-visual

perception a medium in its own right, thereby breaking with the

expressionist, informel or concrete regimes of the abstraction then

in fashion.

“Chronochrome” also echoes the exhibition of Soto at the ARC /

Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1969. In the catalogue

to that show, Jean Clay stressed the highly spiritual dimension of

the “radical dematerialisation” undertaken by the artist. He quoted

Kazimir Malevich’s attack on the theoretical framework that,

according to him, governed the new abstract painting of the day.

“Malevich’s prophecy, made in 1919, is being fulfilled,” stated Clay.

“‘Whoever makes abstract constructions, based on the mutual

relations of colours within the picture is still confined to the world of

aesthetics, rather than bathing in philosophy.’” Whether in the radical

abstraction of the Suprematist painter, or that of the Kinetic artist,

the aim was to escape the logic of pictorial confinement. The work

was to be “open”—to borrow the expression coined by Umberto

Eco with regard to kinetic art. Jean Clay seemed to see Soto’s

Penetrables (1967 onwards) as the extreme incarnation of this logic,

arguing that the ”rain” of fine, translucent and coloured plastic rods

were the ultimate development of the “ambiguous space” that had

first emerged in the first plexiglas reliefs of the 1950s.

The works brought together at Galerie Perrotin in Paris and New York

may disconcert, disorient and seem elusive. The eye—and also the

body in the case of one Penetrable—is subtly trapped, wandering

endlessly in spaces that oscillate between painting and sculpture,

object and image. In the way it enters our perceptual space and

refuses to be fully grasped, a work by Soto is, as Henri Bergson

would put it, an object that no one has seen and that no one ever

will see in its totality. Whether with a wall relief, a sculpture or an

environment, the artist invites us to have an experience that is always

unique, new every time: the experience of an incompleteness, a space-

time continuum that can never be summed up in an image or verbal

account. This may be the prime quality of the monochrome staccato

in which traditional painting and sculpture are singularly subverted

and become atomised in time and space. This unique aesthetic

makes Soto a major figure not only in the history of abstraction, but

also in the greater history of modern and contemporary art.

Image: Jesus Rafael Soto

Press Contact:

Adam Abdalla, Nadine Johnson +212 228 5555 / adam@nadinejohnson.com

Opening: Thursday, January 15, 6-8pm

Galerie Perrotin

909 Madison Avenue

New York

Tue - Sat 10am to 6pm