Rhythms of Modern Life

dal 29/1/2008 al 31/5/2008

Segnalato da

David Bomberg

Paul Nash

C.R.W. Nevinson

Edward Wadsworth

Sybil Andrews

Claude Flight

Cyril Power

Lill Tschudi

29/1/2008

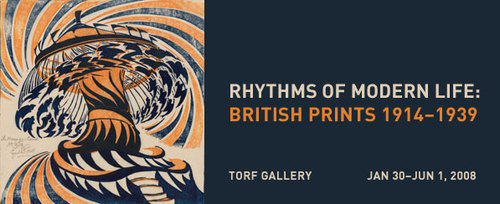

Rhythms of Modern Life

Museum of Fine Arts MFA, Boston

British Prints 1914-1939. Featuring approximately one hundred lithographs, etchings, woodcuts and color linocuts by fourteen artists, the exhibition examines the impact of Futurism and Cubism on British Modernist printmaking from the beginning of World War I to the beginning of World War II. The principal artists represented are David Bomberg, Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevinson, and Edward Wadsworth.

The dynamic synergy of modern man and machine as seen in artistic movements of early 20th century England is the focus of Rhythms of Modern Life: British Prints 1914–1939, an upcoming exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). It highlights the impact of Italian Futurism and French Cubism on British modernist printmaking from the beginning of World War I to the outbreak of World War II. Through a thematic examination of the works of 14 innovative artists, more than 100 boldly graphic prints are showcased. Approximately 70 of these works are drawn from the Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection—a superb assemblage of modern British prints from the heroic days of early modernism to its later 1920s and ’30s adaptation to popular taste. Ten of these (nine prints and one drawing) are recent gifts from the Garfields to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Organized by the MFA, Boston, in collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the exhibition is on view January 30 through June 1, 2008, at the MFA, after which it will be on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and then at The Wolfsonian-Florida International University in Miami. The media sponsor is Classical 99.5 WCRB.

Rhythms of Modern Life highlights the period between the outbreak of World War I and the beginning of World War II, a time of immense social and economic change in Europe stimulated by the technological advancements of the modern age. In this politically and culturally charged climate, the status quo was challenged and new ideologies explored. The arts reflected this change by celebrating newly born abstraction and embracing the accelerating, mechanized speed of modern life. Beginning with the outbreak of the First World War, the exhibition examines the bold, inventive works of British printmakers who were influenced in their war imagery by Italian Futurism. It continues through the short-lived but vital Vorticist movement (1914–1915) and concludes with the colorful contributions of the Grosvenor School of Modern Art (1925–1939). The principal artists represented are C.R.W. Nevinson and Edward Wadsworth—early followers of Futurism and Vorticism—as well as Claude Flight, Sybil Andrews, Cyril E. Power, and Lill Tschudi—the later color linocut artists of London’s Grosvenor School of Modern Art.

A rich variety of printmaking techniques is on view in the show, including woodcuts, drypoints, lithographs, and, above all, color linocuts. A special display in the exhibition highlights how linocuts were made. The newly popularized linocut technique was embraced in the 1920s and ’30s by artists of the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, whose materials and methods are represented by four original linocut blocks for Sybil Andrews’ print Speedway (1934, MFA, Boston, Partial gift of Johanna and Leslie Garfield), as well as instruction manuals and linocut tools.

“Johanna and Leslie Garfield are discerning collectors who, over the years, have generously shared their passion for prints by donating many gifts of important works to the MFA,” said Malcolm Rogers, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Because of their vision, we are now able to introduce to our visitors these striking works by modern British printmakers, whose interpretations of the emerging technological age reflect one

of the most vibrant periods in the history of graphic art.”

A prelude to Rhythms of Modern Life is on view in the adjacent corridor, where seven transportation posters created during this period are on display (to be shown at the MFA only), including: The Zoo by Underground (about 1927) by Clive Gardiner from the MFA’s collection; three works from The Wolfsonian-Florida International University by “Andrew Power,” the name given to works made by Sybil Andrews and Cyril E. Power in collaboration—Aldershot Tattoo (1934), Epsom (1933), and Football (1933)—as well as two posters by McKnight Kauffer from the Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection and The Wolfsonian, and one by Oleg Zinger (from a private collection).

Rhythms of Modern Life is curated by Clifford S. Ackley, who is the MFA’s Ruth and Carl Shapiro Curator of Prints and Drawings and Chair of the Department. In addition to works from the Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection, other prints included in the exhibition are from the MFA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, The Wolfsonian-Florida International University, the Yale Center for British Art, and a Boston-area private collector.

“This exhibition is unusual in combining sober Futurist-derived images from World War I battlefields and radical pioneering abstract works with the later and more playful Art Deco-like color linocuts of the Grosvenor School artists,” said Ackley. “The world of these artists was a brave new, energized one in which the machine dominates and anonymous figures are swept up in regimented or syncopated movement, a world of jazzy animation in which velocity is irresistible as well as exhilarating.”

Organized according to themes that preoccupied these artists, the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are divided into sections: Vorticism and Abstraction, World War I, Speed and Movement, Urban Life/Urban Dynamism, Sport, Industry and Labor, Entertainment and Leisure, Natural Forces, and Linocut: History and Technique.

Vorticism and Abstraction

A number of British artists put their stamp on the modern age in 1914 by blasting the conventions of Victorian art and culture. Calling their movement “Vorticism,” a term coined by American expatriate poet Ezra Pound, their art reflected the “still point” of concentrated energy at the eye of the storm—the storm of social change, political turmoil, and world war. It developed as a radically abstract, hard-edged, geometric style in reaction to the transparent, faceted forms of Cubism and the emphasis on speed and motion characteristic of Futurism. Led by the charismatic painter Wyndham Lewis, Vorticism became the first avant-garde movement in Britain, but it was brief, lasting only two years at its peak. Practitioners included Edward Wadsworth, Henry Gaudier-Brzeska, and David Bomberg. A plaster relief sculpture by Brzeska, The Wrestlers (about 1914, MFA), the inspiration for the artist’s linocut, will be shown only in Boston.

Many of the Vorticist paintings have been lost, so the nine rare woodcut prints by Wadsworth included in the exhibition (of approximately 40 woodcuts rediscovered in the 1960s), provide important documentation of Vorticist conceptions. Wadsworth’s two versions of The Open Window (about 1914, MFA and British Museum, London), as well as his other small early woodcuts in the exhibition, are the purest examples of Vorticist style included in the exhibition. Their mechanically precise contours and degree of abstraction go far beyond Cubism and Futurism, revealing their tendency toward relative stillness and stasis rather than frenetic energy. The Open Window will be represented by two impressions printed in different colors of ink, showing Wadsworth’s restless experimentation.

World War I

C.R.W. Nevinson and Paul Nash served as government-sponsored war artists and their work reflects the torment of history’s first mechanized war. Nevinson was an avowed Futurist, and he undoubtedly endorsed briefly the Futurist belief in the “cleansing” effect of war, but later altered his artistic course after experiencing its horrors. Returning home, his lithographs and drypoints no longer promoted the glory of battle as advocated by the Futurists. Instead, Nevinson’s prints showed men soldiering on, robot-like, over bleak battlefields. But Nevinson also celebrated the beauty of the machine as can be seen in his images of soaring aircraft. Nash served as an officer and war artist in Ypres, Flanders, where 700,000 died. His stark lithographs depict desolation and devastation, with rain and mud washing over an earth ravaged by war, as in The Crater, Hill 60 (1917, British Museum). Wadsworth’s works also reflect the war, but more abstractly. He oversaw the camouflaging of war ships which, because of their optically disorienting designs, were known as “Dazzle Ships.” Wadsworth created a series of woodcuts depicting these optical effects that look forward to the Op Art of the early 1960s, including Drydocked for Scaling and Painting (1918), one of the finest of the Garfields’ ten recent gifts of British prints to the MFA.

Speed and Movement

A fascination with speed and movement is a more positive and energizing aspect of this period. The Futurists’ love of motion was shared by a group of linocut artists associated with the Grosvenor School of Modern Art. Claude Flight, a teacher at the school, was inspired by Futurism’s dynamic motifs, and by the early 1920s, he was championing the linocut as a modern technique well-suited to expressing the concepts of speed and movement. Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power, also of the Grosvenor School, joined him in the creation of bold, graphic statements focusing on popular attractions, such as motorcar racing and amusement parks, which reflected more lighthearted and popular aspects of the modern Jazz Age. Speedway (1934, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection), by Andrews, shows dirt-bike racers speeding toward the viewer in unison in a design for a proposed public transportation poster. Power’s The Merry-Go-Round (about 1930, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection) captures the tornado-like spin of a giant carnival swing and, in its hectic motion, is one of the most extreme of Grosvenor School images.

Urban Life/Urban Dynamism

The dynamism of the modern metropolis and its new sense of the anonymity and isolation of the populace were expressed in works by Nevinson, Power, and Flight. Bustling crowds, busy streets, and various modes of transportation (cars, buses, escalators, and the subway—the Underground or Tube) reflected the rhythms, excitement, and spectacle of the megapolis—London and New York in particular. While some images celebrate the modern city, others emphasize the sense of alienation there, such as Power’s image of passengers crowded together in a busy subway car, The Tube Train (about 1934, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Partial and promised gift of Johanna and Leslie Garfield); this print will be shown alongside two working proofs for the image to show the development of the design.

Sport

The celebration of movement in these British printmakers’ works extended to images of the human body energetically engaged in sport. The growing popularity of spectator sports led to lively modern interpretations of athletes in action. Power captured rowers in The Eight (around 1930, MFA, Partial gift of Johanna and Leslie Garfield), which will be paired in the exhibition with a preparatory drawing for the print showing the changes in design from preliminary ideas to final form. Another work by Power, Skaters (1932, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection), shows the graceful movements of athletes performing in perfectly synchronized motion.

Industry and Labor

The energy, strength, and rhythmic movement of men at work fascinated these artists, who often portrayed them as anonymous cogs in the machinery of everyday life: figures working on an electrical pole, pounding away with sledgehammers, or carrying crates of oranges from a truck. Andrews’ Sledgehammers (1933, MFA, Partial gift of Johanna and Leslie Garfield) offers a view of men at the forge, their faces and arms brightly lit in contrast to the flaring shadows cast by their bodies.

Entertainment and Leisure

In spite of war, unemployment, and social upheaval, entertainment and leisure time still had a vital place in British life. Performers in theaters, concert halls, and circuses gave patrons a brief respite from their daily concerns. Tschudi, one of three women artists represented in the show (along with Sybil Andrews and Eileen Mayo), created Jazz Orchestra (1935, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection) and Rhumba Band II (1936, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection), literal evocations of the Jazz Age with appropriately syncopated visual rhythms.

Natural Forces

While British prints in the years 1914 to 1939 frequently depicted the relationship of man and machine, they also celebrated the beauty and organic movement of natural forces. In Nevinson’s powerful The Wave (1917, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection), which features churning waves, and Andrews’ charming The Gale (1930, Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection), which shows pedestrians fighting the pouring rain with umbrellas, the artists translate the rhythms and patterns of nature into an elegantly stylized visual vocabulary.

Linocut: History and Technique

Grosvenor School artists, led by Flight, celebrated the linoleum block print as a modern technique well-suited to the depiction of modern subjects and not just a teaching tool for children. The soft material gave them a greater ability to express fluidity of movement. The skilled use of hand printing on translucent Japanese paper led to sophisticated and original color schemes and textures. Rhythms of Modern Life features an examination of the history and characteristics of the linocut technique by displaying linocut cutting tools and instruction manuals, as well as the original four linocut blocks used to print Sybil Andrews’ Speedway (lent from her archive at the Glenbow Museum, Calgary).

Image: Cyril E. Power, The Merry-Go-Round, 1929-30. Color linocut. Johanna and Leslie Garfield Collection. Courtesy EB Power & Osbourne Samuel Ltd, London.

Museum of Fine Arts

Avenue of the Arts 465 Huntington Avenue - Boston

Open seven days a week, the MFA’s hours are Saturday through Tuesday, 10 a.m. – 4:45 p.m.; Wednesday through Friday, 10 a.m. - 9:45 p.m. General admission (which includes two visits in a 10-day period) is $17 for adults and $15 for seniors and students age 18 and older. Admission for students who are University Members is free, as is admission for children 17 years of age and younger during non-school hours. No general admission fee is required during Citizens Bank Foundation Wednesday Nights (after 4 p.m.).