L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

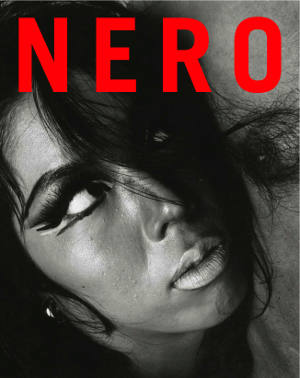

Nero Anno 11 Numero 32 estate 2013

Ruins of exhibitions

A quasi-scientific presentation of seminal exhibitions from the past, through primary evidence such as original texts, images, clippings, scans, transcriptions

free magazine

Section 1 - ROOM AVAILABLE

Section 2 - ADAPTATION

Section 3 - RUINS OF EXHIBITIONS

Section 4 - FELDMANN PICTURES

Section 5 - EXERCISES IN COHERENCE

Section 6 - ARTIST PROJECT

Section 7 - WORDS FOR IMAGES

Section 8 - OFFLINES

Section 9 - A NEW REPORTAGE

Section 10 - TOUCHABLES

Section 11 - MUSTER

Section 12 - THE EXTRA SCENE

Ruins of exhibitions

n. 34 primavera 2014

Exercises in coherence

Amelia Rosselli

n. 33 inverno 2014

Ruins of exhibitions

n. 31 inverno 2013

Exercises in coherence

Dario Bellezza

n. 30 autunno 2012

Body Builders

Walter Siti

n. 29 primavera-estate 2012

Su Roma

Fabio Mauri

n. 28 inverno 2012

MODERNE KUNST NIEUW EN OUD

July 26 – October 3, 1955

Curated by Willem Sandberg

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Contents:

1 Introduction from the catalog

5 Installation views

4 Press clippings

Notes:

Willem Sandberg (1897-1984) was a Dutch typographer and graphic designer, as well as a unique presence in the Dutch cultural world during the 1940s and 50s. He studied in Vienna and then at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Following his return to Amsterdam, he worked as a graphic designer until he was appointed deputy director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1938. He directed the Stedelijk from 1945 to 1962, turning it into one of the world’s leading institutions for avant-garde art. Sandberg presented historic as well as contemporary artists, inventing new forms of display for his exhibitions. He was one of the pioneers of modern curating and exhibition design, transforming the concept of the museum from that of a permanent storage facility to a time-based laboratory. In 1955 he organized the unconventional exhibition Modern Art Old and New in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where he juxtaposed Cobra paintings with African masks and sculptures by Jacques Lipchitz. A similar approach can be found in the work of Karl Ernst Osthaus, the founder of the Folkwang Museum, which combined European and non-European art.

MODERN ART NEW AND OLD

At the beginning of our century, modern art, and with it all the other arts, underwent a revolution of a magnitude we hadn’t seen for a long time. Today, the change perceived at the turn of the new century still appears like the breaking of a dam: the banks of reality and perception, which had contained painting, broke, and the pictorial current started to flow in new directions. The search for the elemental force of figurative art and the search for new paths are the most distinctive features of the arts of our century. This exhibition, installed in the new wing of the Stedelijk Museum, intends to investigate a particular aspect of contemporary art: its sources of inspiration. The “break,” which took place around 1905, ruptured a tradition that had lasted for centuries. Ancestral legacies were no longer accepted by the new generation. The direct perception of nature and the link with reality no longer inspired the work of the first generation of twentieth-century artists. There are many reasons for this attitude. Particularly evident, both to viewers and to critics, are two facts. On the one hand, the invention and perfection of photography made it possible to obtain a picture of reality by purely technical means, thus depriving the visual arts of certain beloved tasks, such as the creation of portraits. On the other hand, the first years of our century witnessed the growth of a sort of mistrust of contemporary reality. The progressive slogans of Western society seemed illusory and immoral; the optimism of the nineteenth century began to be perceived as a hoax. Artists, scientists, thinkers and poets were searching for a new reality – a reality, as Van Gogh had said fifteen years earlier, “more real than literal reality.”

Thus, in looking to the beginning of our century, we relive another revolution, the consequences of which continue to define contemporary art as well as our everyday lives. The artists of the new generation reject the legacy of their fathers in the search for other sources of inspiration in the art of primitive peoples, of early Antiquity and the early Middle Ages. These changes are so significant as to be comparable to the first signs of the Italian Renaissance.

Yet it hardly suffices to notice the break with tradition and the emergence of new sources of inspiration: the most important issue is to identify the reasons behind these changes. And the reasons are not merely related to a refusal of the superficiality of the nineteenth century and of the futile optimism of the Victorian era. They are deeper. In the early twentieth century, shifts in social structure and the dynamism of the working classes led to the emergence of a new type of individual, who could not help but associate the tradition of the past centuries with the subjugation of entire populations. This new individual sought a truer picture of humanity, free from the constraints of the past.

The twentieth-century man is searching for a new form of life, in which all of his rights are respected; it is for this reason that the artist explores unknown territories, in the attempt to give life a new meaning.

Artists thus begin to investigate the deepest aspects of the “human being.” The distrust of the progress of civilization leads to the search for primitive man. Gauguin was the first European artist to search for the lost paradise of the savages of Tahiti. After him, many artists ventured into the South Seas or into Africa, or searched for primitive works preserved in museums, uncovering their artistic value for the first time. In 1906 Kirchner and the “Brücke” masters discovered African sculpture and the art of the Pacific Islands preserved at the ethnographic museum in Dresden. This discovery was decisive for their art. In the same years, the influence of primitive art also left its imprint on the work of Picasso.

What did they notice in the works of the black Africans or in the sculptures of the South Seas islanders? In the first instance, they were obviously struck by the elemental force of their expression. The magical power of masks, sculptures and objects reflected a culture that was inclusive of all branches of life. Each subject was closely connected to the original life force, and each work was relevant to the whole community. Looking for inspiration, modern artists wondered how the primitive artist was able to reach this elemental force. Geometric perfection and a focus on the most expressive shapes are some of the features of primitive art that they decided to incorporate into their work. This is reflected in Gauguin’s claim that “Primitive art is born from the spirit and makes use of nature.”

Primitive artists effectively reduce all forms of nature to their geometric elements, defining the proportions of figures not on a perceptual basis, but rather in accordance with the meaning of the forms themselves. The departure from reality is therefore a reworking dictated by a spiritual need.

The primitive artist does not represent reality, but instead reduces it to a sign, to a form loaded with tension and meaning.

It is also for this reason that primitive art has become a source of inspiration for contemporary art. Looking at these primitive works as though into a mirror, artists have recognized the fulfillment of their own aspirations. What primitive art had reached in its simple and elementary works cor responded to the ideal of this new generation, which consisted precisely in a search for that magical force, that expressive concentration and those elementary shapes. Through primitive art, European artists found a path toward the free creation of a work.

It was only after primitive art had changed European modern art, after Picasso had finished his periode nègre and the German Expressionist masters had produced their most mature works, that there emerged room for a new source of inspiration: modern technology and its forms. It was only after primitive art had revealed the beauty and importance of geometric shapes that it became possible to contemplate the appeal, the rhythm and the aesthetic completeness of a technical product such as a motor or propeller. It makes sense, in fact, that the periode nègre of Picasso and other painters was followed by Cubism.

Cubism was a movement of “order” in European art, determined also by the advance of modern technology. Fundamentally, Cubism is a style in which a certain peculiarity of our time finds its form. Cubism breaks with the tradition of spatial composition bound to a single point of view. It represents the same object from several perspectives at once: from the front, from the side, from behind and from above. This “panoramic overview” of the object represents an abandonment of nineteenth-century individualism, the end of a tradition in which the view of an object was tied to the eye of a painter who never changed position. Movement and mobility are qualities of our time, perpetuated by technology. It is no coincidence that the first and most important Cubist works are still-lifes: compositions of simple geometric objects accessible from all sides. Following the rediscovery of geometry as a founding aspect of primitive art, modern artists were able to recognize the geometric structures inherent in the technical evolution of their time. In this way, modern technology became, thanks to the precision of its standardized geometric products, an important source of inspiration for contemporary art. The beauty of a car and of a technical construction is interpreted, in the works of modern artists, with a new language, a new rhythm.

Cézanne had already anticipated this new way of seeing, pointing out that every form is conducible to geometric elements. The cubists, however, went a step further, and in another direction. They were less interested in converting the forms of nature than in constructing a painting with geometric elements; nature was only a starting point. Just as an engineer designs a car, so they built their works with elementary forms. Out of these geometric elements they created a new order and a new kind of beauty, which, inspired by technology, appeared very up-to-date. Technology has not just inspired the art of our century: many discoveries of modern science have found a visual form thanks to artists. Microscopic preparations of cells and blood counts, samples of organic tissue, astronomical photographs, and many other scientific images have been sources of inspiration for the art of our time. In our century, science has discovered many new territories, to which artists have given shape. Even the most abstract science – mathematics – has become a source of inspiration: mathematical equations, with their intersecting lines, can be traced in the works of contemporary sculptors (Gabo, Pevsner), attracted by games of lines like modern musicians are attracted by the mathematical basis of the fugue and the canon.

In our modern society there exists an additional form of inspiration for contemporary artists – particularly visible in our country – which is characterized by man’s systematic intervention into nature. In order to achieve this intervention, man continuously adapts his geometrical standards. Dams and drains are designed according to schemas of straight lines, such as the roads and military camps of ancient Rome. The application of geometric models in nature is characteristic of our country, and it is not by chance that the most severe and geometric of abstract art forms was developed here: “De Stijl.”

The artists of this movement were able to give form to the rhythm and the laws that man has imposed on nature. It is curious to note that, following his move to America, Mondrian’s work starts to display a new rhythm, which is inspired by the dynamism of a city like New York, and which is also expressed in jazz music.

The two sources of inspiration represented in this exhibition have contributed to a break with tradition, to the refusal of a convenient legacy, to the creation of a new sense of life and its expression through form and color. It has been a long time now since we have seen a similar courage in breaking with the past, and in the desire to build one’s own identity.

This change involves us in a special way since it is not just a few artists that are involved, but rather several generations.

A new style is being born, one that is capable of expressing the meaning of life in our time.

It is important to highlight that in contemporary art these two sources of inspiration are intertwined: primordial human values and modern scientific achievements. Drawing on these sources, the artists of the twentieth century have extrapolated a clear image of the sense of the life of our time.