Celluloid. Cameraless Film

dal 1/6/2010 al 28/8/2010

Segnalato da

Stan Brakhage

Tony Conrad

Cecile Fontaine

Amy Granat

Ian Helliwell

Hy Hirsh

Takahiko Iimura

Emmanuel Lefrant

Len Lye

Norman McLaren

Barbel Neubauer

Luis Recoder

Jennifer Reeves

Dieter Roth

Pierre Rovere

Schmelzdahin

Jose' Antonio Sistiaga

Harry Smith

Aldo Tambellini

Marcelle Thirache

Jennifer West

Esther Schlicht

1/6/2010

Celluloid. Cameraless Film

Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt

The exhibition focuses on a particular art film genre in which footage is produced by creating images directly on film stock. As opposed to other forms of experimental film, the material is removed from its conventional context of use and, interpreted as a canvas by applying diverse artistic processes: painting, collage on celluloid, scrapes and scratches in the emulsion, defamiliarization through chemical manipulations, or the direct exposure of the photosensitive material. In a world pervaded by immaterial digital media, especially younger artists are discovering the aesthetic character of celluloid as a material.

In its exhibition "Celluloid. Cameraless Film", on show from June 2 to August 29, 2010, the

SCHIRN focuses on a particular art film genre in which footage is produced by creating images

directly on film stock. As opposed to other forms of experimental film, the material is removed

from its conventional context of use and, as it were, interpreted as a canvas by applying diverse

artistic processes: painting, drawing, collage on celluloid, scrapes and scratches in the emulsion,

defamiliarization through chemical manipulations, or the direct exposure of the photosensitive

material. Thus even the early days of avant-garde film saw works that also investigate the filmic

image in its material qualities and fathom its relationship to fine arts in ever-new approaches.

Inviting the visitor to follow its varied course, the exhibition presents outstanding examples

of cameraless film and offers a panorama from the 1930s to the present day with works by

21 international artists and film makers such as Stan Brakhage, Tony Conrad, Cécile Fontaine,

Len Lye, Norman McLaren, Dieter Roth, Harry Smith, José Antonio Sistiaga and Jennifer West.

Applying paint to celluloid for coloring black-and-white films had been a current arts-and-crafts

technique since the first days of cinematography. Yet it was only with the emergence of the film

avant-garde that experiments with color and blank film stock became relevant as a generative

principle of film production. The earliest hand-colored films were created by the Italian Futurists

Arnaldo and Bruno Ginanni-Corradini between 1910 and 1912. Entirely in accordance with the

spirit of their day, the painters were looking for a form of pure visual abstraction based on the

principles of music and were fascinated with the novel possibilities film offered for creating

a "music of colors." Unfortunately, only detailed descriptions have survived from their nine direct

animations painted on transparent celluloid. In the early 1920s, the Surrealist photographer Man

Ray was the first to use the rayogram technique, i.e. the direct exposure of objects on photographic plates – a method he had already tested – in film for some sequences of his "Retour à

la Raison" (1923).

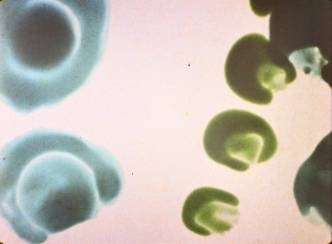

The New Zealander Len Lye (1901–1980) and Norman McLaren (1914–1987), a native Scotsman, who, pursuing different approaches, began to explore the possibilities of producing films

without a camera more systematically in Great Britain in the mid-1930s and whose works became

a landmark for future film artists, are regarded as the actual pioneers of the so-called direct or

cameraless film. Len Lye’s film "A Colour Box" (1935), which the artist painted directly on the

filmstrip, using stencil plates to color the abstract forms, is considered to be the work which

established the genre of cameraless film. Synchronized to a popular Latin American tune, the film

with its bright powerful colors, unusual textures, and the characteristic vibrations and pulsations of

its projected images stood out against all hitherto known results in the field of art film.

The tradition of direct animation was particularly taken up in the US postwar avant-garde film.

Artist, film maker, folk music collector and occultist Harry Smith (1923–1991) was one of the most

colorful protagonists of the genre here. In the late 1940s, he discovered hand-colored film as a

possibility to combine his mystically inspired painting with his interest in music. Influenced by

Wassily Kandinsky’s works and theories, drug experiences, and Eastern philosophy, Harry Smith

produced a number of abstract films of impressive complexity by painting and using intricate

stamping techniques – films whose rhythmically pulsating forms and colors create multi-sensory,

proto-psychedelic pictorial worlds.

The American film maker Stan Brakhage (1933–2003) – one of the key figures of experimental

film in general – repeatedly dedicated himself to cameraless film processes in different periods

of his career, which spanned about fifty years. His film "Mothlight" of 1963, a radically personal

meditation on life and death, already relied on the direct, cameraless approach for its powerful

effect. The dancing flickering composition of moth wings, grasses, blossoms, and leaves ranks

among the few classics of experimental film today and is to be regarded as a key work in the

history of direct animation. It is the first time that material objects provide the visual substance

of a film image. Like in an artist’s collage, Brakhage arranged the translucent insect wings on

the transparent film stock according to basic rules of music and thus produced film images –

structures, forms, and colors of fragile beauty – which could hardly have been obtained by using

a camera.

Since the 1960s, numerous artists and avant-garde film makers have devoted themselves to

direct film experiments. The gamut of works ranges from the Basque painter José Antonio

Sistiaga’s (*1932) vibrating and permanently changing color worlds comprised of thousands

of minutely executed individual drawings to Dieter Roth’s (1930–1998) sequences of letters

scratched into black film. In many cases the film makers also fall back on found footage which

they appropriate by painting on it, scratching it, writing on it, or by applying a number of other

physical or chemical defamiliarization processes. The German artist collective Schmelzdahin’s

(1983–1989) works are frequently based on the transformation of foreign material by means of

chemical, bacteriological or thermic manipulations of the emulsion. The French film "Ville en

flamme" that provided the material for Schmelzdahin’s "Stadt in Flammen" of 1984 was buried in

the ground for one summer, for example, where it was exposed to a natural process of decay.

Subsequently, the fragile damaged material was worked on with a sewing machine and

quadrupled in a copying process frame by frame before a sound track was added.

After a conspicuous boom of direct animation in the 1980s’ experimental film production, the

cameraless approach seems to see a revival on a new level within the context of contemporary

art. In a world pervaded by immaterial digital media, especially younger artists are discovering the

aesthetic character of celluloid as a material, whose sensory, particularly haptic qualities could

hardly be achieved with electronic pictures. For his series of cameraless studies titled "Available

Light," the artist Luis Recoder (*1971), for example, exposed the film rolls in their light-proof

packaging to a precisely controlled incidence of light. The resulting filmic tableaus of light and

intense, pulsating color gradients resemble works by artists like James Turrell or Robert Irwin.

California-based Jennifer West (date of birth unknown) has produced a body of 50 direct films

since 2004. She subjects her material to complicated interventions and procedures in a performative mise-en-scène, as it were. She uses all everyday materials conceivable, from food and

lipstick to motorcycle tires, to work on different formats of film up to 70 mm wide gauge, which are

also bathed in more or less effective substances, the respective concept revealing itself only

through the title, such as in the case of her work "Film Wearing Thick Heavy Black Liquid Eyeliner

That Gets Smeary (70 MM film leader lined with liquid black eyeliner, doused with Jello Vodka

shots and rubbed with body glitter)." West’s immersive psychedelic filmic spaces, many of which

already appeal to the sense of taste, smell, or hearing through the work’s title, powerfully recall

the vision of film as synaesthetic art that pervades the history of direct film from Len Laye to Harry

Smith and Stan Brakhage.

LIST OF ARTISTS:

Stan Brakhage, Tony Conrad, Cécile Fontaine, Amy Granat, Ian Helliwell,

Hy Hirsh, Takahiko Iimura, Emmanuel Lefrant, Len Lye, Norman McLaren, Bärbel Neubauer,

Luis Recoder, Jennifer Reeves, Dieter Roth, Pierre Rovère, Schmelzdahin, José Antonio

Sistiaga, Harry Smith, Aldo Tambellini, Marcelle Thirache and Jennifer West.

CURATOR: Esther Schlicht (Schirn).

PROJECT MANAGEMENT: Heide Häusler.

CATALOGUE: Zelluloid. Film ohne Kamera – Cameraless Film. Edited by Esther Schlicht and

Max Hollein. With a preface by Max Hollein and texts by Yann Beauvais, Marc Glöde, Heide

Häusler, and Esther Schlicht. German/English edition, 192 pages, 300 illustrations, Kerber

Verlag, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-86678-395-9, 29,80 € (Schirn and bookshops).

"ZELLULOID" WEBLET: A special microsite – http://www.schirn.de/zelluloid – has been created to

accompany the exhibition. The weblet, which will be going online with the opening of the show,

consists of two areas. One offers information on the artists in the exhibition and their films, of

which excerpts will be available. The site’s second area invites users to participate: here, film

material can be digitally scraped, scratched, painted, or manipulated chemically. Users may feed

their works into their preferred social network with a mouse click and thus recommend the

exhibition at the Schirn. The microsite has been developed and sponsored by Scholz & Volkmer.

The exhibition is sponsored by FREUNDE DER SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT E. V.

Image: Len Lye, a colour box (detail 3), 1935

PRESS OFFICE: Dorothea Apovnik (head), Philipp Dieterich

SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT, Römerberg, D-60311 Frankfurt, phone: (+49-69) 29 98 82-118,

fax: (+49-69) 299882-240, e-mail: presse@schirn.de

Press preview: Tuesday, June 1, 2010, 11:00 a.m.

SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

Römerberg, D-60311 Frankfurt.

OPENING HOURS: Tue, Fri–Sun 10 a.m. – 7 p.m., Wed

and Thus 10 a.m. – 10 p.m.

ADMISSION: 7 €, reduced 5 €, family

ticket 14 €; in combination with the exhibition "Uwe Lausen. All’s Fine That Ends Fine" 14 €,

reduced 10 €; in combination with the exhibition "Peter Kogler. Projection" 9 €, reduced 6 €;

in combination with the exhibition "Mike Bouchet. New Living" 9 €, reduced 6 €; in combination

with the exhibitions "Peter Kogler. Projection" and "Mike Bouchet. New Living" 12 €, reduced 9 €.

Free admission for children under 8 years of age.

SUMMER TICKET: Visitors may recommend an exhibition for the first time by passing their ticket for "Zelluloid" on to friends and thus granting them free admission to the show.