Under Destruction

dal 13/10/2010 al 22/1/2011

Segnalato da

Nina Beier

Marie Lund

Monica Bonvicini

Pavel Buchler

Nina Canell

Jimmie Durham

Alex Hubbard

Alexander Gutke

Martin Kersels

Michael Landy

Liz Larner

Christian Marclay

Kris Martin

Ariel Orozco

Michael Sailstorfer

Arcangelo Sassolino

Jonathan Schipper

Ariel Schlesinger

Roman Signer

Johannes Vogl

Chris Sharp

Gianni Jetzer

13/10/2010

Under Destruction

Tinguely Museum, Basel

Under Destruction is a group exhibition, featuring twenty internationally known contemporary artists, that examines the use and role of 'destruction' in contemporary art. Predominantly kinetic, the show largely consists of works whose mechanisms reveal themselves in real time to the viewer. The strikingly spectacular nature of some works is complemented by an unexpected sense for subtlety and quietude in other works, the combination of both progressively revealing the rich diversity of destruction in contemporary art.

Curated by Chris Sharp and Gianni Jetzer

Nina Beier & Marie Lund, Monica Bonvicini, Pavel Büchler, Nina Canell, Jimmie Durham,

Alex Hubbard, Alexander Gutke, Martin Kersels, Michael Landy, Liz Larner, Christian

Marclay, Kris Martin, Ariel Orozco, Michael Sailstorfer, Arcangelo Sassolino, Jonathan

Schipper, Ariel Schlesinger, Roman Signer, Johannes Vogl

Under Destruction is a group exhibition, featuring twenty internationally known

contemporary artists, that examines the use and role of “destruction” in contemporary art.

Fifty years after Jean Tinguely's historic Homage to New York (1960) the present

exhibition proposes a series of alternative approaches to a theme traditionally associated

with the more spectacular and inherently protest-oriented work of Jean Tinguely, Gustav

Metzger and others in the 50s and 60s. "If nothing can be created, something must be

destroyed", is how Rosalind Krauss succinctly summarized Georges Bataille's La part

maudite (The Accursed Share, 1949). While this phrase can basically describe the ethos of

Under Destruction, the exhibition raises the stakes normally linked with such a deleterious

theme. Not only does it explore the various modes of destruction in art, but, more

importantly, it also addresses to what ends it is implemented. Indeed, the exhibition

reflects on the subject from a series of angles, perceiving destruction as everything from a

generative force to environmental memento mori, and from consumer fallout to a form of

poetic transformation.

Predominantly kinetic, the show largely consists of works whose mechanisms reveal

themselves in real time to the viewer. The strikingly spectacular nature of some works is

complemented by an unexpected sense for subtlety and quietude in other works, the

combination of both progressively revealing the rich diversity of destruction in

contemporary art. Under Destruction can be divided up into a series of overlapping themes

and categories, which are anything but hard and fast, and which inevitably blur in and out

of one another.

The contributions of Nina Canell and Pavel Büchler engage with destruction as a form of

transformation. In Canell's water-and-cement based work Perpetuum Mobile (40 kg) (2009-

2010), in which water is transformed into a mist via sonic vibrations which hardens a

nearby sack of cement, a kind of destruction is broken down to some of its finest,

molecular components. Meanwhile Büchler's series Modern Paintings (1999-2000),

consists of flea-market bought paintings, which are un-stretched, inserted in a washer, and

reconstituted by the artist on a stretcher, such that they resemble Art Brut abstractions.

Modes and effects of consumption are addressed in the contributions of Johannes Vogl,

Monica Bonvicini, Ariel Orozco, and Michael Landy. Vogl's absurd, homemade contraption

Untitled (Machine to produce jam breads, 2007) which senselessly produces pieces of

bread with jam on them, addresses questions of overproduction and consequently waste.

Comprised of a relatively fragile veneer of plaster precariously placed above a real floor

which gradually fills up with holes made by visitors, Bonvicini's installation Plastered

(1998), testifies to the consumption and deterioration of architecture by those who use it.

Orozco's Doble Desgaste (2005), takes a more metaphysical approach toward

consumption, speaking to the concentrated and deliberate dissipation of effort. In this

photographic documentation of an “action“, Orozco systematically draws a portrait of a

cube shaped eraser in graphite, photographs the portrait, erases it with the same eraser,

redraws the eraser on the same piece of paper, photographs it, erases it, and so on until

the eraser and the portrait are gone. Finally, Michael Landy's uneasy relationship with the

accumulative identity of consumption is registered in the video documentation of his

celebrated work Breakdown (2001), in which the artist had all 7,227 of his possessions,

classified, dismantled, and destroyed in a department store in central London.

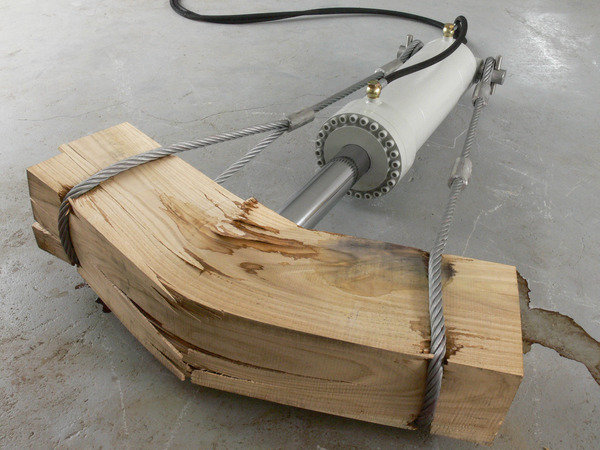

The consequences of consumption inevitably filter into the environment and technology.

Arcangelo Sassolino's Untitled (2007), perceives technology as a brute, destructive force,

which cannot be disassociated from environmental issues. Activated by the viewer through

a motion detection sensor, Untitled is a hydraulic arm that gradually pushes into and

destroys a large block of wood. Liz Larner's Corner Basher (1988), likewise depends

directly on the visitor participation. This piece consists of a drive shaft mechanism, the

activation and speed of which is controlled by the viewer, that swings a chain into and

destroys the nearby corner wall.

Jonathan Schipper's The Slow Inevitable Death of

American Muscle (2007-2008), pits technology against itself in an allegory of

obsolescence, consumption and destruction. The installation is comprised of two cars that

slowly enact a head-on collision over the course of an extended period of time, and in

doing so, inevitably bring the memento mori onto the stage. Indeed, a close kinsman of

destruction, the memento mori necessarily dominates the mood of several works in this

exhibition. Christian Marlcay's video installation Guitar Drag (2000), which consists of

imagery and a soundtrack of a guitar being dragged behind a pickup truck, is rich in

association, the most symbolic being a historically fraught vanitas.

Roman Signer's methodically engineered acts of decimation, here represented by a trio of

works, the videos Stuhl (Chair, 2002), Zwei Koffer (Two Suitcases, 2001) and Rampe

(ramp, 2008), which respectively and heterogeneously depict the destruction of a chair, the

contents of a suitcase and a small truck, have a way of always bringing issues of mortality

into play. Nina Beier and Marie Lund's History makes a Young Man Old (2008), departs

from the theme of technology and uses performance to facilitate a sense of deterioration

wrought by time and use.

For this piece, the artists' take turns rolling a crystal ball from wherever it is purchased in

the city of an exhibition venue to the exhibition site itself. This powerful but economic

work stages a loss of clarity, brought on through an attrition that is determined by forces

beyond its control.

Meanwhile, Kris Martin's 100 years (2004) which quite simply consists of a bomb set to

go off in 2104, dislocates the moment of destruction into a distant temporal elsewhere,

and in doing so, incorporates that elsewhere and the destruction it is destined to undergo

into the present, thus extending the domain of destruction well beyond the parameters of

the exhibition itself. Where Martin's bomb trades on the future of destruction, other works,

such as Ariel Schlesinger's Bubble Machine (2006), deal in its specter, envisaging

destruction as pure potential. True to the spirit of Tinguely's quasi unhinged tinkering

aesthetic, Schlesinger's madcap machine consists of a mechanism placed on top of a

wooden ladder, which periodically drops bubbles of soap onto a small, electrified series of

coils, making the bubble burst into flames. Here destruction becomes a more controlled and

evocative force. If the melancholy frustration of this work is not without a certain humor, a

few other works in this exhibition venture off the deep end into a kind of slapstick

decimation.

Alex Hubbard's video's for example, such as Cinéopolis (2007), is a humble

masterpiece of antic decimation. Replete with a Foley soundtrack, this video portrays the

Hubbard carrying out a series of damaging acts upon a small movie screen from a bird's

eye point of view, such as torching a group of metallic balloons and then tarring and

feathering the screen. Martin Kersels Tumble Room (2001), takes humour to a more

spectacular, if acrobatic level. For this piece, Kersels had a room constructed, outfitted it

with all the accoutrements of a little girl, and placed it on a mechanism, which rotated the

entire room end over end, until it gradually turned the somersaulting contents into dust.

The kinetic sculpture is also accompanied by a video of a dancer, perilously negotiating the

topples and turns of the room as it tumbles. Here destruction is deployed as bravura, as a

kind of dandified testimony to being beyond the reach of destruction, or its effects.

Humour has always been a key component to Jimmie Durham's work, and can certainly be

found in his performance St. Frigo (1996). The result of beginning his daily routine for

about ten days in a row by throwing cobble stones at a refrigerator for one hour, this piece

speaks to destruction as a daily ritual. By dint of this repetitive and iconoclastic act,

Durham was able to assert a destructive tendency as a form of affirmation. Repetition

likewise informs Alexander Gutke's The White Light of the Void (2002). This 16mm film

installation simulates the meltdown of blank film stock, as if the film jammed in the

projector, whereupon the bulb promptly burns through the celluloid. This small

conflagration in turn produces an amoeba-like form that expands outward from the centre

of the frame, swallowing it up and returning the film to its opening white frame, intact, and

the loop resumes.

This work, which symbolically deals with issues of death, the afterlife

and renewal, can be seen as a metaphor for the entire exhibition in which destruction itself

is often a force of cyclical renewal. Where Gutke's work brings these metaphysical issues

into the picture, Michael Sailstorfer's contribution, which is comprised of a high speed HD

video transferred to 16mm film, uses that same picture, so to speak, to depict what for all

intents and purposes looks like some kind of big bang, cosmic explosion: that, it turns out,

is just a light bulb being shot by a rifle.

Swiss Institute, New York: March 2 - April 30, 2011

Image: Arcangelo Sassolino - Untitled, 2007, Installation

Sammlung Galerie Nicola von Senger, Zürich

© 2010 Courtesy of the Artist

Presse contact Museum Tinguely

Isabelle Beilfuss Tel: +41 61 6874608 fax: +41 61 6819321 E isabelle.beilfuss@roche.com

Thursday October 14, 6:30 PM

Tinguely Museum Basel

Paul Sacher-Anlage - Basel

Opening hours: Tuesday – Sunday 11 am – 7 pm (on Monday closed)

Admission fees: Adults: CHF 15

Pupils, students, apprentices, senior citizens, disabled: CHF 10

Groups of 20 persons: CHF 10/ each

Children and adolescents up to 16 accompanied by an adult: free

School classes with 2 accompanying adults: free

(1 day advance booking by telephone compulsory)

Guided tours:

Public guided tours: Each Sunday, 11:30 am (no reservation required, price: admission ticket)

Private guided tours for adults: Reservation at tel.+41 61 681 93 20