NO! The Art of Boris Lurie

dal 25/3/2011 al 14/5/2011

Segnalato da

25/3/2011

NO! The Art of Boris Lurie

Chelsea Art Museum, New York

The show inaugurates a series of exhibitions devoted to the NO!art Movement and its members and affiliates, as well as other long-neglected or suppressed humanist strains in the art of the latter half of the Twentieth Century. Lurie is one of the legendary figures of the East Village avant-garde of the fifties and sixties, a resistor against the institutional structure of art in his day and what he called the 'investment art market' and one of the powerful voices for humanity in an art world officially devoid of political or social awareness.

Presented by the Boris Lurie Art Foundation

The first exhibition in New York of art from the Boris Lurie estate will take place at the Chelsea Art Museum, from 26 March 2011 until 15 May 2011. The show will inaugurate a series of exhibitions devoted to the NO!art Movement and its members and affiliates, as well as other long-neglected or suppressed humanist strains in the art of the latter half of the Twentieth Century. The vitriol and fury of Lurie and his cohorts still runs in the veins of their art fifty and more years after it was created; it is as fresh, powerful, and, remarkably, beautiful, as it was in the cultural near-vacuum in which it was created. Lurie is one of the legendary figures of the East Village avant-garde of the fifties and sixties, a resistor against the institutional structure of art in his day and what he called the "investment art market" and one of the powerful voices for humanity in an art world officially devoid of political or social awareness.

The avant-garde has historically played the role of art's conscience, and has, accordingly, been little heeded. Art is, after all, a mode of production, an industry, a market, a fact that only gradually came into being and only fairly recently became transparent and all-consuming. Art itself was long "the realm of freedom," the voice of what all men valued, or professed to value, but which an ossified social reality denied us. The avant-garde arose as the fact that art and its promise of a better world was merely the shill, or at best the dupe, of the real order, the circus if not the bread, became inescapable.

But the real order is resourceful, and has learned to turn even that which resists, or even loathes it, to its ends. When an avant-garde is sufficiently at odds with reality, it is simply ignored; it remains a voice in the wilderness, at least until such time as the wilderness can be developed. As with Dada, or Fluxus, or, more recently, performance art, that might require decades. It is only now that art history is beginning to assess the many strains of serious, critical, and humane art that dwelled in the shadow of the sanctioned movements of the fifties, sixties, and seventies, now, that is, that what Arthur Danto and others have described as the end of art has rendered the very notion of an avant-garde pointless. Avant-garde implies a concept of progress, or at least direction, and art in our time is, for good or ill, a stranger to either.

As a deathcamp survivor, Lurie's artistic concerns were, understandably, quite different from those of the artists among whom he found himself on his arrival in American after the war. As Sarah Schmerler remarked in her catalogue essay for Lurie's 1998 gallery show, Bleed, 1969, "Most American artists of the Forties were fresh out of art school. Lurie was fresh out of Buchenwald." There are deeply humane and inherently European aspects of his work, not to mention aggressively political dimensions, that rendered him rather an alien presence among his fellow artists in the New York of the forties through the seventies (and beyond). His animus against Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Neo-Dada, all movements with which aspects of his own work share certain visual and tactical qualities, is essentially a resistance against the widespread (and typically American) desire to leave the war behind and to forget is ravages in the midst of the wealth and optimism that victory and consequent economic ascendancy had engendered. Lurie was by no means stuck in the past, but having lived it, he refused to behave as if it had never happened, or that other horrors were not ever-present or ever-threatening.

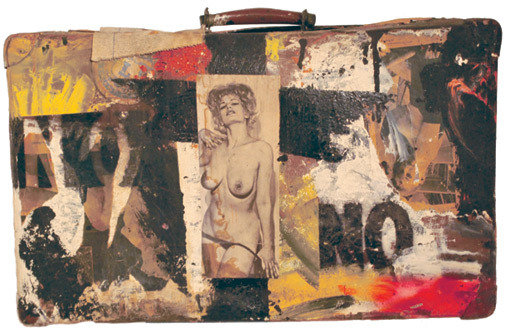

In the fifties, sixties, and seventies, much of Lurie's work, such as the infamous Railroad Collage (1963) not only shocked and confused, but even repulsed much of the viewing public. Some of his juxtapositions of explicit imagery of sexuality against others of brutal death and dehumanization even now defy rational engagement: they are visual aporias that short-ciruit analysis. His Dismembered Women and Pin-Up collage series, among others, at once assert that the objectification of women is violence against women and that female sexuality is a fundamental and ineradicable force, ideas difficult at best to incorporate in a single work.

Theodor Adorno famously remarked, "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric." Lurie stands among the great artists, figures like Tadeusz Borowski, Primo Levi, and Paul Celan, who have responded in art to the greatest inhumanity ever perpetrated and shown just what poetry after Auschwitz might be, and why it must be. In the battle for the soul and humanity of art, Lurie was a hero of the resistance, the resistance against compromise, indifference, perversion, and co-optation or manipulation by the market.

Chelsea Art Museum

556 West 22nd Street (Corner of 22nd St. and 11th Ave.) New York, NY 10011

Open Tuesday–Saturday, 11am–6pm

Thursday 11am–8pm

closed Sunday and Monday