Last Exit: Pictures

dal 14/3/2012 al 20/4/2012

Segnalato da

Troy Brauntuch

Jack Goldstein

Louise Lawler

Sherrie Levine

Robert Longo

Allan McCollum

John Miller

Steven Parrino

Richard Prince

David Robbins

David Salle

Laurie Simmons

Alan Vega

James Welling

Lionel Bovier

14/3/2012

Last Exit: Pictures

Blondeau Fine Art Services BFAS, Geneve

This exhibition is based on the Image Division Collection (London), whose adviser is the curator of this project; it seeks to map out certain of the problematics of 'representation' that came to the fore between 1976 and 1989 and to question certain of their articulations.

Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine,

Robert Longo, Allan McCollum, John Miller, Steven Parrino, Richard

Prince, David Robbins, David Salle, Laurie Simmons, Alan Vega, James

Welling

Curated by Lionel Bovier

The title of this exhibition refers to a text published in 1981 by Thomas Lawson, in which he advocated the importance of painting as a

medium for the emerging ‘appropriationist’ practices that lay at the heart of that era’s cultural debates about ‘re-presentation’. More than thirty

years after the pioneering exhibition organised by Douglas Crimp, Pictures (Artists Space, New York, 1977), this new exhibition comes as a

modest addendum to The Pictures Generation, a retrospective of the eponymous movement curated by Douglas Eklund at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art (New York, 2009).

This exhibition is based on the Image Division Collection (London), whose adviser is the curator of this project; it seeks to map out certain of

the problematics of ‘representation’ that came to the fore between 1976 and 1989 and to question certain of their articulations. For example,

the opposition made in the 1980s between photography and painting within appropriation is contradicted by the relative space accorded to

each of these media in exhibition and blurred by the typology of the works in question. And the prevailing narrative of a single ‘generation’ of

artists committed to appropriationist practices is denied by the continuity of these problematics with those manifested in the work of younger

and older artists. Finally the inclusion of some less well-known figures allows us to add a certain number of names to the standard ‘cast list’ of

the ‘Pictures’ generation.

In addition to the artists present in the 1977 Pictures exhibition (Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine and Robert Longo), we have

brought together works by David Salle (who was one of the first to take note of Goldstein’s work and who, early in his career, had a number of

affinities with Goldstein and Brauntuch), Richard Prince (often incorrectly included among the artists exhibited by Crimp), David Robbins

(whose series of portraits, ‘Talent’, ironically represents the New York scene of the 1980s in Hollywood guise), and Louise Lawler and Laurie

Simmons, both of whom were at first represented by Metro Pictures—the gallery founded by Helene Winer and Janelle Reiring in 1980, where

the trajectories of almost all these artists intersected.

What these artists had in common was not so much their choice of a technique or a mode of expression as their new relationship to images.

As Douglas Crimp wrote in 1977, ‘While it once seemed that pictures had the function of interpreting reality, it now seems that they have

usurped it. It therefore becomes imperative to understand the picture itself, not in order to uncover a lost reality, but to determine how the

picture becomes a signifying structure of its own accord.’ This drive towards analysis combined with recognition of the extraordinary semantic

‘opacity’ of images is what underpins all these different approaches, whatever the sources used (images of spectacle or war, commercial or

artistic, banal or indecipherable, absent or abstract) or the nature of that use (repetition and appropriation, re-contextualisation and criticism,

fiction and narrativity).

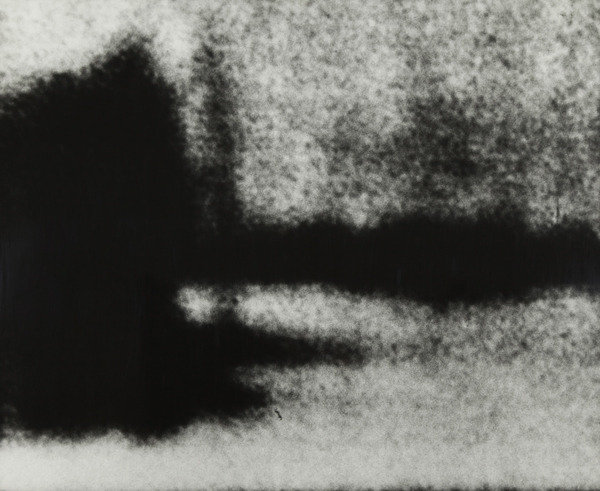

The work of Allan McCollum, which began before that of the ‘Pictures’ generation, is included here in the form of a piece from the series of

‘Perpetual Photographs’; these bear witness to his quest to determine the nature of an image through its ‘mediatisations’ (enlarged

photographs of a found image from film) and thus confer on it a ‘generic’ dimension. James Welling and John Miller, both represented here by

paintings, also seek images that are ‘generic’ or ‘weak’ not in terms of their banality or definition but of their ‘dis-appropriation’: they are images

of images, resembling thoughts produced for and by others and that no one would dream of claiming for themselves.

A few years later, when the practices of the ‘Pictures’ generation had already been instituted, the ‘necrophiliac’ relationship that Steven Parrino

claimed to hold with painting already suggested a turning point and a new story of the image. The diptych presented here, which Parrino called

his ‘theory of painting’, confronts a monochrome with a photocopy of a B-movie monster riveted under Plexiglas. It is as if our relationship to

the image could no longer be conceived unless in the form of a zombie—the half alive, half-dead beings that have haunted the cinematic

imagination of the last thirty years just as ‘reference’ has haunted contemporary art.

The key issue for this exhibition is therefore not a question of history nor of medium; rather the object is to circumscribe the redefinition of the

role and nature of images that occurred during that era. At the heart of it is the aspiration to show ‘images’ in every possible state

(appropriated, displaced, painted, re-photographed and combined); to follow them as they migrate from one support to another; and to

emphasise the importance of a form of critical ‘iconology’ that these artists, despite their generational or aesthetic differences, had—for the

last time in the history of Western art—in common. In the 1990s and 2000s, alongside the appearance of digitalisation and the hyper-

availability of information, there emerged an entirely new sensibility towards images, their representation and their mode of existence, and this

was as true of society in general as it was of art.

Lionel Bovier, February 2012

Image: Allan McCollum, Perpetual Photo No. 210 1989

Silver gelatin print sepia toned

124 x 101 cm. 48.8 x 39.75 in.

Press contact:

Philippe Davet T +41 22 5449595, F +41 22 5449599 philippe@bfasblondeau.com

BFAS Blondeau Fine Art Services moved in 2000 to 5 rue de la Muse in the heart of the Quartier des Bains in Geneva 1205 Genève—Switzerland

Hours: THUR-FRI 14h-18h30, SAT 11h-17h.