Jozef Robakowski

dal 1/11/2012 al 11/1/2013

Segnalato da

1/11/2012

Jozef Robakowski

Zak / Branicka, Berlin

Der Linie nach. An artistic manifesto on analytic and structural cinema since the 1960s. Inspired by the theories of Karol Irzykowski, Robakowski has focused on technique and a laboratory analysis of the medium of film.

The energy of a lazy line...

One moment it is straight, then it swells, slants, only to stop, to move, it picks up speed, turns left, turns right, runs, runs,

runs, skips the tracks, stands up, trembles, stiffens, but does not burst, takes on color, reddens, moves off again, runs,

hurries a bit, turns blue, then green, flees ever faster, only to turn right, then left, then right again, it shouts something, what,

halt, but it barrels on, without stopping, violet, maybe blue, no, yellow, it twists, straightens out, lifts up, falls down, hovers

on the edge, takes fright, turns violet, blue, white, lifts up, falls, goes wavy, wavy, wavy, slows down, slowly stands,

trembles, once more, trembles, powerfully, moves, bends, left, right, but straight, always straight, runs off, ever further,

black, gray, pale, swells, breathes, melts...

Józef Robakowski (2012)

ŻAK | BRANICKA proudly presents an exhibition by the legendary avant-garde film artist of the 1960s and

1970s, Józef Robakowski (*1939). Its main subject is the line, one of the most simple and radical motifs, and

one which has repeatedly cropped up in this artist’s work since the 1970s.

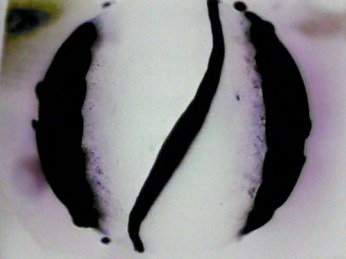

An ordinary gesture—a line scratched on a frame of film (Idle Line, 1992)—he sees as analytic, an element that

visualizes time and motion, the most basic elements of cinematography. In other works Robakowski has used the

line to explore the synchronicity of sound and image. He often sees the course of the line as a kind of action that

releases energy: “In 1976 I pursue it with a movie camera, but a moment later I also run, drive, jump... to obtain a

filmic image of my biological vitality. By giving this absurd task to the camera I take away its original function.” Films

and video works with the line thus not only explore the typical psychophysical function of the image on the viewer, but

also attempt to give the abstract image human attributes.

This exhibition is an artistic manifesto on analytic and structural cinema, which Robakowski has been exploring since

the 1960s. One of the artist’s key premises is the disavowal of the narrative form of film and cinema’s

representational function. Inspired by the theories of Karol Irzykowski (1873-1944), that the most important element

in cinema is light and its function, and not the image of reality, Robakowski has focused on technique and a

laboratory analysis of the medium of film. Examples here are the non-camera films Test I, 22x, and Test II (all 1971),

created by manually working on the film tape (scratching, perforating, etc.), thus releasing light directly from the

projector at a certain rhythm. Another very important premise was to liberate the camera from the control of the eye

and the attempt to render the image objective, as exemplified by the film I’m Going (1973), and later by Po linii...

[After the line] (1977) or My Leg Hurts (1990). Robakowski’s experiments of the 1960s and 1970s drew, on the one

hand, from the tradition of the Russian Constructivists, on whose legacy the artist was raised, and on the other from

the contemporaneous work of Fluxus, Situationism, and Actionism, which addressed the same problems as those

tackled by conceptual artists like Vito Acconci and Jan Dibbets. His work bore a remarkable resemblance to figures in

experimental cinema across the world, and to such artists as Malcolm Le Grice and Paul Sharits.

To understand how radical and avant-garde Robakowski’s position was at the time, we have to consider the political

situation and the film community of the day. To free himself from the control of the socialist regime, the artist shut

himself in his home and made films which today we would call home videos or left the city with his camera, to the

forest, for instance, where he had no fear of his equipment being confiscated. On the other hand, the artist

ostentatiously cut himself off from the professional film environment (from “cinematography”), which he criticizes for

surrendering to the state administration and delusions: “The moment finally came, in around 1975, when we had to

bid farewell to all of socialist cinematography. Then we, workshoppers, were the only ones left, a ‘cinema of broad

horizons,’ made at our own expense.”

If we trace his artistic approach, we find that Józef Robakowski is the Witold Gombrowicz of Polish cinema. Watching

Robakowski’s films, such as Poles Having Fun (1989), From My Window (1978-99) and My Videomasochisms

(1990), we automatically recall Gombrowicz’s Diary 1953–1956, which begins with the words: “Monday: Me,

Tuesday: Me, Wednesday: Me, Thursday: Me.” Moreover, with a simple gesture to the camera in his performances

Robakowski—like Gombrowicz’s finger—unmasks the false “mug” of the official films. What he seeks (like

Gombrowicz searching for the “real peasant”) is real cinema, often using blank tape, light pulse generators, and

camera motion, as an extension of the body.

Józef Robakowski (*1939) co-founded the avant-garde groups Zero-61, Oko, Pętla, Krąg, and Warsztat Formy Filmowej, whose members included Wojciech

Bruszewski, Paweł Kwiek, Ryszard Waśko, and Zbigniew Rybczyński. His works have been shown at the Sao Paulo Biennale (1973), documenta 6 in Kassel

(1977), and the Sydney Biennale (1982), and at such institutions as De Appel in Amsterdam (1975), Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh (1972), Hayward

Gallery in London (1979), and Centre Pompidou in Paris (1983). Recently Robakowski’s work has enjoyed a great deal of interest – a large retrospective of his

work was organized in 2012 by the Center for Contemporary Arts in Warsaw and Toruń, and the National Museum in Gdańsk.

Opening: November 2, 2012, 6 to 9 pm

Zak / Branicka

Lindenstrasse 35, Berlin

Hours: Tue.-Sat. 11a.m. - 6p.m.

Free Admission