Soto

dal 26/2/2013 al 19/5/2013

Segnalato da

26/2/2013

Soto

Centre Pompidou, Paris

The Venezuelan artist Jesus-Rafael Soto, who died in 2005, was one of the leading figures in the development of kinetic art in Europe. The gift by the artist's family of 20 key works makes it possible to reconstruct his career. The exhibition traces his journey from his first Plexiglas reliefs of the 1950s to the monumental volumes of the years from 1990-2000.

curator of the exhibition Jean-Paul Ameline

Le Centre Pompidou pays tribute to the Venezuelan artist Jesús-Rafael Soto, who died in 2005,

one of the leading figures in the development of kinetic art in Europe in the second half of the

20th century.

Paradoxically, until now Jesús-Rafael Soto was little represented in French public collections.

The gift to the State by the artist’s family in 2011 of twenty key works dating from 1955 to 2004,

is an outstanding group which makes it possible to reconstruct the career of a major artist,

famous for his Penetrables. The exhibition traces his journey from his first Plexiglas reliefs of

the 1950s to the monumental volumes of the years from 1990-2000.

Living in Paris from 1950, the artist developed a body of work in constant dialogue with

the founders of abstraction, Mondrian, Malevitch and Moholy-Nagy, and with his contempories

Agam, Pol Bury, Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely and Daniel Spoerri. From the 1960s, Soto achieved

an international reputation and exhibited in London, Krefeld, Berne, Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris

and elsewhere.

From 1979 the Centre Pompidou has presented the artist’s latest works. In 1987, an emblematic

work entitled Volume virtuel [Virtual volume], was commissioned from Soto by the Association

des Amis du Centre Pompidou [Friends of the Centre Pompidou] on the occasion of the

institution’s 10th anniversary. This monumental work was to remain in the Centre’s Forum for

10 years, testifying to the close relationship forged between the institution and the artist.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue published by Éditions du Centre Pompidou,

edited by Jean-Paul Ameline, curator of the exhibition.

CURATOR’S INTRODUCTION

The Soto donation provides the opportunity to comprehend the rigour and subtlety of a body of work

tirelessly constructed in dialogue with both the great pioneers of abstract art, Mondrian, Malevich

and Moholy-Nagy, and his contemporaries, primarily Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely. Indeed, Soto’s first

Paris paintings exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles of 1951, the year fafter he moved to Paris,

already demonstrate his intention to “make Mondrian move”.

His first exhibited works were serial paintings, intended to break away from the canonical rules

of abstract composition and to arrange a rhythmic succession of colours and forms and suggest their

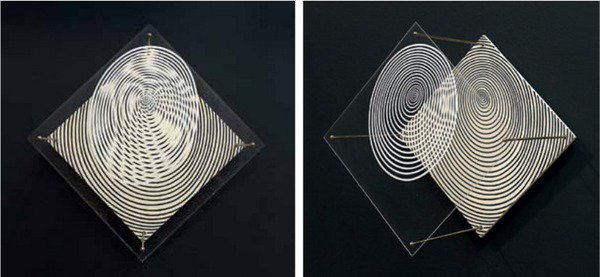

optical movement. In 1953, after Soto had discovered the work of Moholy-Nagy in books, he used

Plexiglas (Perspex) to make his new abstract works. Motifs in these works are repeated twice, first on

wood, then on a Plexiglas panel placed 20 cm in front. Soto thus brought about “perceptual explosions”

which would develop in the following years. These explosions, as Soto hoped, liberated geometric forms

and planes of colour from their static state. They seem to vibrate and move.

In 1955, Soto was invited by Denise René and Vasarely to exhibit his first Plexiglas pieces in

“Le Mouvement” exhibition. Here he saw Marcel Duchamp’s motorised Rotary demisphere which in the

following months inspired him to make his Plexiglas Spiral. This is in fact in two parts: a black spiral

occupies the background of the wooden panel on which it is painted and allows a painted white spiral to

appear on a sheet of Plexiglas placed in the foreground. As the viewer’s gaze moves it creates the illusion

that the spiral is rotating.

Prolific in the number of Plexiglas works made (a total of 38), nonetheless Soto stopped making them in

1958, refusing to allow his exploration to be identified with a material. It was at this time that he adopted

metal in the form of thin tubes or monochrome squares against hand-painted black and white striped

backgrounds. Treated in this way, rods and squares placed in front of these striped backgrounds

seem to take on an illusory instability. This aspiration to make the work of art not a finished set of subtly

composed forms and colours, but a means of introducing a moving reality, brought the artist closer to

both the new Parisian realists and the Germans of the Zero group (Mack, Piene, Uecker, etc.) with whom

he exhibited many times in these years from 1960-1965.

From 1959-1962, scrap iron, usually found, would be reused by Soto for his works. This was what some

critics were to call his “baroque” period. Then close to Daniel Spoerri and Jean Tinguely, Soto visited

scrap metal dealers and flea markets and then tried to prove that he could “dissolve” any metal with the

aid of his striped backgrounds and make it dematerialise through optical vibration.

From 1963, Soto abandoned found materials. His first installations using new wire curved into

unpredictable shapes appear as a counterpoint to straight lines on an evenly painted background:

These are the Escrituras. At the same time, Soto also began to use rods suspended from nylon

threads in front of striped backgrounds. This is, finally, about having found the “pure vibration” released

by the poetry of found materials. The solutions he developed will be long-lasting. Their classicism

intentionally distinguishes them from the optical games shown in the Op Art exhibitions. Opposing such

events, Soto, through his works, puts the emphasis on revealing the kinetic nature of the real, marked

by the threefold dimension of space-time-material.

Thus in 1967, he hung his first Penetrable at the Denise René gallery with the idea of including himself

– and the visitor with him – in the midst of rods suspended from the ceiling. Viewers could perceive

the work optically from outside or pass through it and place themselves inside the piece thus created

by getting involved and becoming an integral part of it.

Thus, Suspended Volume (1968) offered as a donation, is one of the group of early works involving the

viewer. With its three elements (a wall panel of painted lines restored after Soto’s death, a first vertical

volume of blue painted rods and a second vertical volume of black painted rods), it is the missing link

in Soto’s work between the pre 1967 works (in which optical vibration dominates) and the Penetrables

in the strict sense in which the viewer’s perception is as much tactile as visual.

“With the Penetrable” said Soto, “we are no longer observers but constituent parts of the real.

Man is no longer here and the world there. He is fully there and it is this feeling that I want to create

with my enveloping works. It isn’t about driving people mad, about stunning them with optical effects.

It’s about getting people to understand that we are steeped in the trinity of space-time-material”.

After 1975, Soto’s work went through one last evolution. While kinetic art was eclipsed by the current

trends in art, Soto, while generously responding to commissions for public artworks and assisting

with numerous retrospective exhibitions in museums, gave his work a new rigour by returning to reliefs

in which coloured squares again play an essential role.

During the 1980s, a series of works drew on Soto’s investigations: this is the series, Ambivalences, the

product of his reflections on the last period of Mondrian’s work, which culminates in the Boogie Woogie

series in which colour explodes into hundreds of tiny squares arranged over the canvas. Like Mondrian,

Soto arranged his coloured squares over striped backgrounds, placing them both in opposition to them

and as counterpoints to others. Each colour, painted on squares of different sizes (but all located in the

same plane of the picture), seems to react to its neighbours in its own way and give the viewer the optical

sensation that the square painted in it projects to a greater or lesser degree from the background of the

picture.

It is evident that the Soto donation, in its breadth and diversity and the museum quality of the works

offered, at last endows French public collections with an essential reference archive on one of the

internationally recognised major figures in kinetic art.

Image: Spirale, 1955. Paint on wood and plexiglas, metal 30 x 30 x 28 cm Donation, 2011. Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Georges Merguerditchian / Dist. RMN-GP © Adagp, Paris 2013

Press Officer:

Anne-Marie Pereira tel +33 (0)1 44784069 e-mail anne-marie.pereira@centrepompidou.fr

Centre Pompidou

75191 Paris cedex 04

Opening Hours

Exhibition open every day 11am-9pm except Tuesdays

Admission

€11 to €13, depending on the period

Concessions: €9 to €10 Valid all day for the Musée national d’art moderne and all exhibitions