Teppei Kaneuji / Tehching Hsieh

dal 26/6/2013 al 24/8/2013

Segnalato da

26/6/2013

Teppei Kaneuji / Tehching Hsieh

Ullens Center for Contemporary Art UCCA, Beijing

In "Towering Something" Kaneuji gathers icons of modern culture and everyday objects and assembles them into sculptural and cut-paper collages, resulting in Frankenstein sculptures that explore a separation of purpose and form. A concise exhibition of the work of one of the world's most important performance artists.

TEPPEI KANEUJI: TOWERING SOMETHING

In “Towering Something,” Kaneuji gathers icons of modern culture and everyday objects—hula hoops, shopping carts, plastic dinosaurs, Doraemon—and assembles them into sculptural and cut-paper collages, resulting in Frankenstein sculptures that explore a separation of purpose and form. “White discharge,” or plastic resin, is poured over the mass of objects and then drips down to cover some pieces entirely, harden into stalactites, and pool on the ground. Intended to fill a mold, the resin instead acts as a shell, indicating a monstrous confrontation and embrace of the ambiguous and meaningless.

TeppeiKaneuji studied sculpture at the Kyoto City University of the Arts, completing his MA in 2003. His sculptures are fashioned from found objects whose original functions—symbolic and otherwise—are anything but obscure. Employing consumer items including coat hangers, plastic toys, marker pens, and even a set of kitchen knives, Kaneuji’s works explore the possibility of interacting with materials in ways other than those preordained by the social and economic values usually assigned to them. Kaneuji’s work seeks out symbol-object relationships and then intentionally smothers their projected meanings by connecting lines, turning shapes inside out, and flip-flopping roles of “inner” and “outer.”

The inspiration for his signature “White Discharge” series came when Kaneuji saw a Mercedes Benz and adjacent pile of dog excrement blanketed in snow. Moved by the levelling effect of the thick, white substance, the artist began trying to recreate his own versions, collecting unrelated objects and covering them with white starch powder. Kaneuji was still a student at the time, and notes of his university experience in general that he learned in the course of his studies that he did not have to develop a concept before starting a work, but rather could operate on a more affective basis, worrying about explanation after the event. Both playful and contemplative, Kaneuji’s work collapses the division between thinking and making that dominates industrial society. In White Discharge (Built-up Objects #28) (2012), scissors, diabolo toys, and action figures combine to make a structure that loosely resembles a biplane. The white resin that covers the structure meanwhile serves at once to homogenize the component parts and make the airplane reading possible, at the same time as it creates a powerful sense of stillness—the resin having hardened as it was dripping downwards.

Using materials that might seem more at home in a children’s playroom than a museum, Kaneuji’s works are tactile and inventive. The “Games, Dance & the Constructions” series comprise two-dimensional sculptures mixing manga cutouts with photographs. The “Ghost Building” series meanwhile uses mirrors as the background for the skeletal frames of children’s sticker sheets when all the stickers have been removed. Kaneuji describes the effect he hopes to engender with his art as “a sense of encountering things that seem familiar but that we do not really understand.”

This exhibition at UCCA offers audiences a change to engage with this captivating and ingenious artist, with the artworks displayed accompanied by a 15-minute video depicting the process by which the “White Discharge” series was made.

----

TEHCHING HSIEH: ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE 1980-1981

UCCA Exhibition marks the first Mainland China showing of the complete installation of a landmark work from highly influential Taiwanese/American performance artist

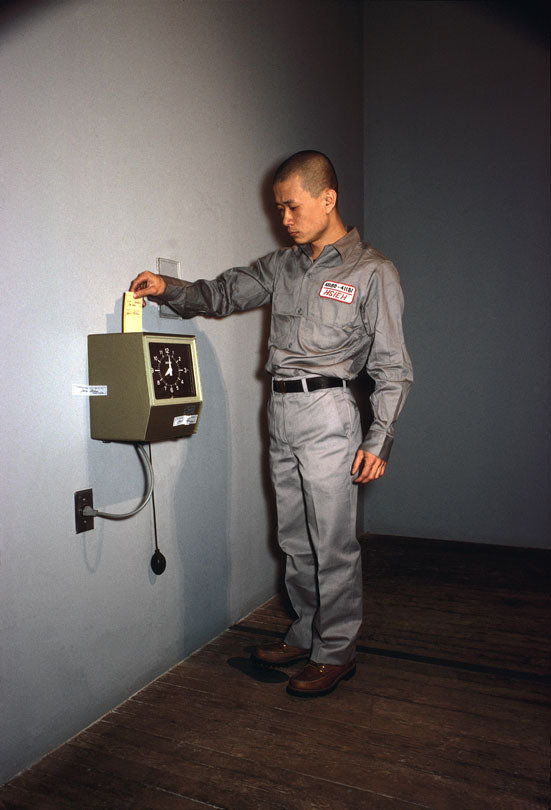

UCCA is pleased to present Tehching Hsieh One Year Performance 1980-1981, a concise exhibition of the work of one of the world’s most important performance artists, and the founding influence on Chinese performance art after 1989. Born in Taiwan and based in New York City, where he conceived and executed five “One Year Performances” in the late 1970s and 1980s before abruptly ceasing to make and show new work, Hsieh is a pioneer of the avant-garde whose practice is currently undergoing a scholarly re-examination. The full installation from one of his most iconic works, “Time Clock Piece” (One Year Performance 1980-1981)—a work in which the artist punches a time clock every hour for an entire year—will be shown in the UCCA Long Gallery alongside posters and statements pertaining to his other four “One Year Performances” and “Thirteen Year Plan.”

Tehching Hsieh (b. 1950, Taiwan) is renowned for the way his works collapse the distance between art and life. Hsieh’s five “One Year Performances,” executed between 1978 and 1986, give flesh to concepts central to theoretical investigations into the mechanics of late capitalism—presence and surveillance, production and control, discipline and submission. In his first One Year Performance, “Cage Piece”, the artist locked himself in a cell in his New York studio for a year, no reading, writing, talking, watching television, or listening to the radio permitted for the duration. This was followed by “Time Clock Piece” several months later, and then “Outdoor Piece,” in which the artist stayed outside, not entering any interior space for a year. With incarceration and homelessness unlikely states to enter into voluntarily, Hsieh’s works demonstrate extraordinary levels of individual will. Hsieh’s fourth piece however is relational in its focus. For a year, the artist was tied to another performance artist, Linda Montano, with an eight foot-long rope, the rules being that the two remain bound together but unable to touch each other. The final two pieces in Hsieh’s extraordinary oeuvre include the “No Art Piece,” a total removal from all art practice for a year, closely followed by “Thirteen Year Plan,” a period in which Hsieh made art but did not show it publicly, ending on the artist’s birthday on the eve of the new millennium, December 31, 1999.

The five “One Year Performances” and Hsieh’s 1986 – 1999 “Thirteen Year Plan” are so compelling in part because they are so opaque. The “Time Clock Piece,” or “One Year Performance 1980-1981,” comprises a poster, an artist’s statement and witness statements, a record of missed punches, the time clock itself, 366 time cards, 16 mm time-lapse film, 366 filmstrips, and the uniform that Hsieh chose for himself. The artifacts that remain after a year of preternatural commitment to a set of rules are not much more illuminating than the rules themselves. Photographs that Hsieh took of himself every time he clocked in—pose fixed, expression blank—are presented in movie form, a piece that runs at 24 frames per second, and lasts just over 6 minutes in total. The brevity of the film combines with the paucity of residual evidence to emphasize the proposition set out in “Cage Piece” that life is no more than “serving time,” with one moment no more important than the next.

The second part of this exhibition at UCCA is a six-part collection of posters and statements covering Hsieh’s output from 1978 to 1999, a total of 21 years of radical art practice. The contemplative and visionary nature of Hsieh’s work is grounded in its own place and time, but also highly transportable both physically and conceptually. The exhibition, mounted in a hall that was once a factory chamber and the site of so much clocking in, marks the first time that the complete documents of “Time Clock Piece” are shown in full in mainland China, as well as Hsieh’s first solo presentation in the People’s Republic, offering the Beijing audience a unique opportunity to engage with one of the most provocative and perplexing art practitioners working in the last century.

The exhibition is part of an ongoing focus on performance at UCCA this year, marked also by the inclusion of several performative pieces in the recent exhibition DUCHAMP and/or/in CHINA and to be capped with an exhibition by Tino Sehgal this coming autumn.

Press contacts:

Carmen Yuan, UCCA: carmen.yuan@ucca.org.cn

Jade Ouk, Sutton PR Asia: jade@suttonprasia.com

Opening June 27, 2pm - 3.30pm

UCCA

798 Art District, No. 4 Jiuxianqiao Lu, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China 100015

Tuesday to Sunday 10:00am – 7:00pm

Last entry at 6:30pm

General admission: ¥10 per person

FREE for:

students (with valid ID)

UCCA members (with card)

children under 130 centimeters

disabled visitors

seniors over 60 (with valid ID)

FREE admission on Thursdays