12th Biennale de Lyon

dal 9/9/2013 al 28/12/2013

Segnalato da

Jonathas de Andrade Souza

Thiago Martins De Melo

Ed Atkins

Bjarne Melgaard

Trisha Baga

Takao Minami

Matthew Barney

Meleko Mokgosi

Neïl Beloufa

Paulo Nazareth

Gerry Bibby

Paulo Nimer Pjota

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Yoko Ono

The Bruce High Quality Foundation

Laure Prouvost

Antoine Catala

Lili Reynaud-Dewar

Paul Chan

James Richards

Ian Cheng

Matthew Ronay

Dan Colen

Tom Sachs

Petra Cortright

Hiraki Sawa

Jason Dodge

Mary Sibande

Aleksandra Domanovi

Gustavo Speridiao

David Douard

Tavares Strachan

Erro'

Nobuaki Takekawa

Roe Ethridge

Ryan Trecartin

Lizzie Fitch

Edward Fornieles

Hannah Weinberger

Gabriela Frioriksdottir

Ming Wong

Robert Gober

Yang Fudong

Karl Haendel

Anicka Yi

Fabrice Hyber

Zhang Ding

Jeff Koons

Ann Lislegaard

Nate Lowman

MadeIn Company

Vaclav Magid

Helen Marten

Gunnar B. Kvaran

Thierry Raspail

9/9/2013

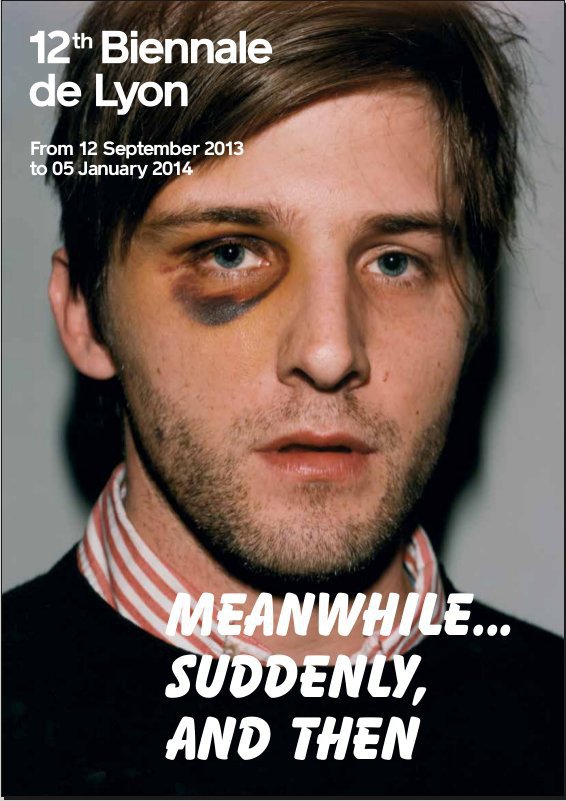

12th Biennale de Lyon

Different Venues , Lyon

Meanwhile... suddenly and then. The exhibition brought together artists from all over the world who work in the narrative field and use art to experiment with the modalities and mechanisms of storytelling. It gives pride of place to the ingenuity and inventiveness of contemporary artists in undoing mainstream narrative codes and off-the-peg plotting devices in order to tell new stories differently.

Guest Curator: Gunnar B. Kvaran

Artistic Director of the Biennale de Lyon / Contemporary Art: Thierry Raspail

Biennales de Lyon – the rules of the game

Since the first Biennale in 1991, I have invited my guest curators to think in terms of a key

word. The word remains the same for three successive Biennales and is always a common word

with topical connections and a fairly vague semantic range, a word capable both of artistic and

societal interpretations. The first word, in 1991, was History. Then in 1997 it was Global, followed

by Temporality in 2003 and, from 2009 to 2013, Transmission.

When I submitted the word Transmission to Gunnar B. Kvaran, he responded in literal fashion

with the word Narrative. The term is no more a subject than it is a title. It is merely the starting point

for a dialogue upon which we are constructing three platforms. In the first place an exhibition –

however the works are combined and in whatever venue, whatever is chosen and whatever is left

out, it is still all about designing an exhibition. Second, Veduta – the laboratory of visual creation and

experiment, in which artists in residence, the collection of the Lyon Museum of Contemporary Art,

works from the exhibition, and amateurs of all ages and social backgrounds combine to construct a

new visual relationship with the world. And third, Résonance – a vast, polyphonic mass of creativity

in which artists’ collectives, young galleries, neo-institutions, or just people taking risks with form,

pay homage to the irrational in a sort of counterpoint to the exhibition, in the plural, and in the most

valid of tenses, the present – the only tense that is independent of time.

The Narrative

Art, for some, is a structured language with an obvious narrative, for others it is a silent image

with something that can vaguely be said about it. Like Italo Calvino’s Cloven Viscount, it is a split

terrain with permeable front lines, an area in which two opposing and antagonistic factions operate.

On one side the idea that anything other than language can tell a story is rejected. On the other

side, like Nelson Goodman, people think that works of art exemplify form, feeling and ideas, and can

construct whole worlds. The dispute is as old as it is insoluble.

People have always sought to explain the world through narrative. It began with myths. Then

came gods and legends, and then History. And, quite clearly, everything pertaining to language,

whether articulated or not, spoken or written or kept silent – hysteria, poetry, literature, thought.

But what do images tell us? Does Altdorfer’s Battle of Alexander have anything to say? Is it

perhaps telling us that from Issus in the Hellenist period until William IV of Bavaria nothing ever

changed, that things were always the same and History has to be reinvented? And does Piero della

Francesca’s Baptism of Christ reveal anything to us? Is it saying that the agreement between East

and West is fragile or that the spirit is all one? Do these images relate all that, or none of it?

And yet, whether it is the work of art telling the story or History speaking, there is nevertheless

something there which looks for all the world like a narrative.

The Text

In the middle of the 1980s a new ‘universal’ hero came into existence in the form of Text.

Born of the sacred marriage of European structuralism and American academic textuality, it spread

across the world, becoming in the process an ‘intertext’ and then a generalised ‘supertext’. Fredric

Jameson put it like this: “The older language of the ‘work’ – the work of art, the masterwork –

has everywhere largely been displaced by the rather different language of the ‘text’, of texts and

textuality – a language from which the achievement of organic or monumental form is strategically

excluded. Everything can now be a text in that sense (daily life, the body, political representations),

while objects that were formerly ‘works’ can now be re-read as immense ensembles or systems of

texts of various kinds.”1 Thus the ‘dictatorship’ of the future, borne up until then on the shoulders

of messianic History, the one of modern times, was eroded in favour of an infinite narrative

encompassing the here and now, the event and, of course, the image.

It was at this precise moment that new modes of composition for visual narratives were seized

upon by artists, or rather invented by artists. All of a sudden they were climbing up walls, filming

things, wearing masks, drawing, sculpting, and all at the same time. They construct things, move

things around, meander, concentrate and superimpose temporalities, supports, shadows and

inversions, unfold things, uncover things. They have discovered the complexity of the world’s

temporalities and the micro-narratives that inform the world. Whatever it is they are doing, they are

telling stories, which is another way of saying that they are transmitting.

Tell me a story

For Gunnar B. Kvaran to place narrative side by side with transmission is to state the obvious

about what happens (“Reality is what happens”, as someone said). Gunnar B. Kvaran’s response to

the neo-modernism that covers our walls with a patina of soft nostalgia is to place a new emphasis

on form, which is a totally new form of thought. And the form of that thought is probably what is

most eloquent about it. A story can be as good as you like but what makes it stand out in the end

is the relevance of its form. The form creates the meaning by forming the narrative.

The Little Prince said, “Tell me a story”. The poet drew it.

Meanwhile... suddenly and then

by Gunnar B. Kvaran

Novelists and screenwriters always hope they have an interesting story. These

days, politicians too and advertisers are all on the look-out for a good story that can

be used to influence voters and consumers. Not only are there “countless forms of

narrative in the world”, as Roland Barthes put it, but now they are everywhere and

an integral part of our daily life.

The Biennale de Lyon 2013 has brought together artists from all over the world

who work in the narrative field and use art to experiment with the modalities and

mechanisms of storytelling. The exhibition gives pride of place to the ingenuity

and inventiveness of contemporary artists in undoing mainstream narrative codes

and off-the-peg plotting devices in order to tell new stories differently.

The art of these artist-storytellers comes in many and varied forms and uses a

wealth of different registers, materials and techniques. So the exhibition naturally

includes sculptures, paintings, fixed images, animated images, arrangements of

text, arrangements of sounds and of objects in space, as well as performances. It

highlights the way (or rather ‘ways’) in which young artists of today – according

to whether they work in Europe, Asia, Latin America, Africa or North America – are

imagining the narratives of tomorrow: narratives that dispense with the suspense

and excitement of globalised fiction as practised in Hollywood, on television,

or in the best-sellers of world literature. Theirs are totally new narratives that

defamiliarise us with the world and restore the deep-rooted strangeness and

complexity that classic storytelling devices have always sought to iron out or to

stifle. These are art narratives that enable us to see and understand the world in

a new light and more intelligibly.

Thus, a whole range of stories, of all kinds and sorts, developed by these

artists from lived experience or imagination, from anecdotes of everyday life as

well as from social phenomena and significant historical events, will be spread out

around the various host venues of this year’s Biennale: La Sucrière, the Museum

of Contemporary Art and the Bullukian Foundation, as well as, for this edition, two

more venues, La Chaufferie de l’Antiquaille and the Saint-Just Church. Certain

works will inveigle their way into private houses and apartments in Lyon for the

duration of the Biennale and they and the stories they tell will be displayed and

transmitted in whatever way the inhabitants of these unusual venues may choose

to invent for them. There will be as many narratives as there are visitors able to

absorb and, in their turn, relate them, changing them as they retell them, adding to

them, and no doubt twisting them, too. They will spread in various ways – through

conversations, rumour, over the social networks – and will give rise to a host of

unpredictable, inflated, discontinuous, fragmentary stories.

The 2013 edition of the Biennale de Lyon grapples with the idea of contemporary art biennials

as the construction of a shared world rather than a given. This is why the title we chose for the

2013 Biennale avoids any attempt at a descriptive summary of the works exhibited but seeks rather

to divert them from any easy explanatory framework, the effect of which too often is only to thwart

their inherent variety of meaning.

Meanwhile... Suddenly, And then

This choice of title (or titles), which places the accent on storytelling devices, is a way of

asserting the importance for an exhibition of going with the flow of its subject, which in this case is

a renewed attention to form; form as a generator of meaning, and the idea that in a narrative it is the

way you tell it, the way you make a story of it – the invention of a new narrative form – that counts.

The Biennale de Lyon 2013 has wholeheartedly taken this question on board – in the way it

is organised, the way it is advertised, in the spatial arrangements and even in the way it unfolds.

A weekend in October is devoted to the question of narration in video and the contemporary art

film, with special screenings and discussions. And there will be another in November devoted to

performance. But, also, a whole set of new contributions by writers and theorists will be published

and broadcast throughout the Biennale. Each of these projects will beget potential new sequences,

and strengthen the shared interrogations that originally inspired the Biennale.

If this new edition of the Biennale de Lyon aspires above all else to being a collective and

shareable event operating on many levels, I have nonetheless taken a completely subjective

approach to it, for which I assume full responsibility. The list of artists involved traces the path that

led me to give it its present form. Erró, Yoko Ono and Alain Robbe-Grillet are the artists who first

impressed me, through their works, with their ability to invent a politics of visual narration. They did

this by challenging the myth of a natural narrative order as used by any social, moral or political

order for purposes of establishing and consolidating itself.

Robert Gober, Jeff Koons, Matthew Barney, Fabrice Hyber, Tom Sachs and Paul Chan form a

second circle of guests – people I have worked with over the last fifteen years who have been

involved in this groundbreaking exploration, working out ever more different ways of giving visual

form to stories. In working with them and talking to them over the course of various exhibitions,

I have come to understand how important a large collective exhibition conceived around these

questions can be. However, to avoid ever being lulled into the fallacy of blinkered thinking, and

aware as I am of the need to be constantly on the look-out for new modes of interpreting and

narrating the world, I am also presenting a whole new generation of artists that I discovered in the

course of my research and my many journeys around the world for the Biennale de Lyon. They,

in their turn, are reinventing different ways of rendering the complexity of today’s world through

narrative experiments with forms beyond words.

Press contact:

Laura Lamboglia 3 rue du Président Edouard Herriot 69 001 Lyon, France T +33 (0)4 27466560 P +33 (0)6 83278446 llamboglia@labiennaledelyon.com

Professional preview:

Tuesday 10 September

La Sucrière: open from 11am to 7pm

Museum of Contemporary Art, Bullukian Foundation, Saint-Just

Church and the Chaufferie de l’Antiquaille: open from 12 to 7pm

Wednesday 11 September

All venues: open from 10am to 10pm

Venue for the private view and award ceremony for the 2013

Francophone Artist Award: La Sucrière, 6.30 pm

Exhibition venues:

La Sucrière -Les Docks, 47-49 quai Rambaud, Lyon 2

The Museum of Contemporary Art (macLYON) Cité Internationale, 81 quai Charles de Gaulle, Lyon 6

The Bullukian Foundation 26 place Bellecour, Lyon 2

The Chaufferie de l’Antiquaille (former district boiler plant) Rue de l’Antiquaille, opposite No. 6, Lyon 5

The Saint-Just Church Rue des Farges, Lyon 5

Opening hours

Tuesday to Friday: 11am to 6pm

Saturday and Sunday: 11am to 7pm

Closed on Mondays

Special opening times during the Festival of Lights in December: Thursday 5, 10am to 6pm; Friday 6, 10am to 9pm; Saturday 7 and Sunday 8 December, 10am to 7pm.

Late opening on the first Friday of every month, 6-9pm: 4 October, 1 November and 6 December 2013; and 3 January 2014.

Closed 25 December 2013 and 01 January 2014

Prices

Full price: €13

Concessions*: €7 For under-26s, job seekers and large families.

Free admission

Under 15 years old; students on diploma courses in the Rhône-Alpes Region; art-school students; art history and plastic arts students; RSA beneficiaries; MAPRA and MDA card holders; m’RA card holders; ICOM card holders; disabled visitors.