The Renaissance and Dreams

dal 8/10/2013 al 25/1/2014

Segnalato da

8/10/2013

The Renaissance and Dreams

Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris

Bosch, Veronese, El Greco... With one famous exception - Durer, presented at the end of the exhibition - Renaissance artists did not paint their own dreams. They painted the dreams that other had, or could have had, showing them sometimes as narratives of dreams taken from mythology and Biblical history, and sometimes as nightmarish visions.

An exhibition organised by the Réunion des musées nationaux - Grand Palais, Paris, and the Soprintendenza del Polo Museale Fiorentino.

curators:

Alessandro Cecchi, director of the Galleria Palatina and the Boboli Gardens at the Palazzo Pitti, Florence,

Yves Hersant, professor at the Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris,

Chiara Rabbi-Bernard, art historian

Itself sparked by a dream of a new life, the Renaissance set great store by dreams, their interpretation and

representation: in political and social life, with the revival of divinatory practices; in literature, both prose and

poetry (Francesco Colonna and Rabelais, Ariosto and Tasso, the Pléiade and d’Aubigné...); in medical and

theological debates, especially during the terrible witch hunts throughout Europe from the fifteenth to the

seventeenth centuries. There then flowered what might be called 'the old regime' of dreams, based on the idea

that sleep and dreaming put us in contact with the powers of the other world. When we dream, do we escape the

constraint of our own bodies to enter into contact with the divine? Or are we delivered up to foreign 'demons'?

What credit should be accorded to oneiromancy? Is it possible to draw up a vocabulary of dreams, as in "The

Interpretation of Dreams"?

Renaissance painters and engravers dealt with these problems in their manner: that is, artistic and not

theological, philosophical or medical. The questions they asked, which are proper to art, go beyond the debates

of the time and still fascinate us today: is there a profound affinity between the imagery of art and that of

dreams? How can an artist possibly represent what a dreamer sees? In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries,

although some artists explored dreams as a revelation of another world, be it holy or hellish, and others used

them to transform everyday experience or heighten its erotic dimension, the more demanding artists saw dreams

as a metaphor for art itself. Life became a dream and the artist was a dreamer.

With one famous exception — Dürer, presented at the end of the exhibition — Renaissance artists did not paint

their own dreams. They painted the dreams that other had, or could have had, showing them sometimes as

narratives of dreams taken from mythology and Biblical history, and sometimes as nightmarish visions. But they

all stumbled on the same obstacle: painting a dream, that is, not an appearance but an apparition, means trying

to objectify what cannot be objectified. Dreams are elusive. But the very impossibility of representing them

aroused in artists seeking to test the limits of their art the desire to take up the challenge; to show their skill in

representing what cannot be represented, more spectacular still than storms; and to give their works greater

power by striking the imagination and the eyes by a particularly vivid image. To try to paint an oneiric world, as

the medieval artists had already done (but in a different context), was in many respects to transgress the limits of

art; it meant broadening the field and asserting new powers.

Depending on the subject, period and region, and their individual talents, artists responded very differently to this

challenge. There is a huge difference between a Dream in the Quattrocento and a Dream in the next century,

just as there was between works from northern and southern Europe as shown in variety of artists on display —

whether famous like Bosch, Dürer or Michelangelo or less well known like Mocetto or Naldini. Logically and

chronologically, the exhibition goes from night and sleep, from dawn - where for Renaissants manifest the true

dreams - to the final awakening, with the main part devoted to dreams and visions. Visitors will therefore see in

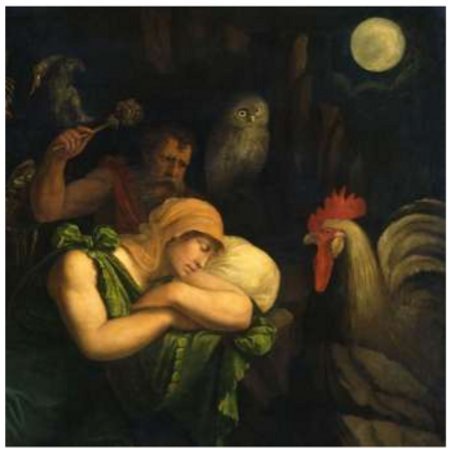

succession figurations of the night (Michelangelo and Battista Dossi), sleeping beauties whose soul is vacant

(like those of Paris Bordon) before passing to a decisive stage, in which artists paint not only the body of the

sleeper and dreamer, but the dream itself. Sometimes to show "true dreams" taken from the Bible (Jacopo

Ligozzi) or lives of saints (Garofalo, Veronese), sometimes, on the contrary, to conjure up infernal visions (Jan

Brueghel, Hieronymus Bosch...). Some artists juxtapose the dreamer and the dream in the same space (as

Giotto did); others imagine meditations (El Greco), while the northern artists thrust us straight into a nightmare.

We see things in the night, too; far from extinguishing the visible, the darkness releases other spaces for games,

freedom or anguish.

The argument of the exhibition, which also includes some enigmatic works (Raphael's Dream, by the engraver

Raimondi), is not only historical. No doubt it is useful to recall the importance of the 'old regime' of dreams,

largely effaced from our memories by the successive and antagonistic revolutions of psychoanalysis and the

neurosciences; but it is even more important to invite visitors to dream, too, to keep the paths of imagination

open by offering them, for the first time, such a collection of Renaissance works.

An exhibition presented at the Palazzo Pitti, Florence, from 21 May to 15 September 2013

Image: Battista Dossi, Allégorie de la Nuit (detail), around 1543-1544, oil on canvas, 82x149,5 cm, Dresde, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen,

Gemäldegalerie, © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Elke Estel / Hans-Peter Kluth

Press contact:

Elodie Vincent 01 40134761 elodie.vincent@rmngp.fr

Florence Le Moing 01 40134762 florence.lemoing@rmngp.fr

GALERIES NATIONALES DU GRAND PALAIS

Porte Champs-Elysées, 3, avenue du Général-Eisenhower 75008 Paris

open: every day from 10 a.m. to 7:30 p.m,

late night until 10 p.m. on Mondays and Fridays.

Exceptional closing on December 25

rates : 11 €, concession 7,5 €

free for visitors under 16 years

square 26-30: 4 people between 26 and 30 years : 30 €