Two Exhibitions

dal 15/1/2014 al 21/1/2014

Segnalato da

15/1/2014

Two Exhibitions

Xavier Hufkens, Bruxelles

David Hammons continues to explore the relationship between materials, images and their meaning. The group exhibition instead explores the personal vision of each artist trought their main and best known works.

David Hammons

One of ten children brought up by a single mother, Hammons moved to Los Angeles in 1962 and studied art at the Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts) from 1966 until 1968 and the Otis Art Institute from 1968 until 1972. He settled in New York City in 1974 and gained a reputation for making work that interrogated cultural stereotypes and racial issues. He first rose to prominence with his Body Prints series. Often resembling X-rays, they are direct imprints of the body made on paper with grease. Injustice Case (1973, Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art), which dealt with the trial of Bobby Seale, a co-founder of the Black Panthers, is a celebrated work from this period. Contemporaneous with these was the Spade series, which feature garden shovels as defiant metaphors for race – an appropriation of a derogatory term used by prejudiced whites. These works were the precursors to the found-object sculptures that he began making in the late 1970s using cheap and discarded materials such as elephant dung, Afro hair and chicken bones. Hammons’ use of ‘low-grade’ materials can be seen as a reaction against what he perceived to be ‘clean’ art, but they also reference to Arte Povera, an acknowledged source of inspiration.

Although Hammons has recently embraced a more painterly style, he continues to explore the relationship between materials, images and their meaning. His latest series of paintings, three of which are exhibited here, have been partially obliterated by found materials: old textiles, abraded tarpaulins and grubby plastic sheets. The materials allude to the dirtiness and poverty that often characterises the reality of black urban life. Executed in a colour palette reminiscent of the American Abstract Expressionist painters, for example Willem De Kooning, the sumptuous, gestural paintings are just visible at the edges and corners of the works, and through the holes in the materials that cover them. While the canvases have every appearance of having been randomly and haphazardly obscured this is, in fact, a carefully orchestrated concealment, with the fabrics and plastics forming a compositional element in their own right. The startling juxtaposition of the beautifully painted canvases and the soiled coverings – not to mention the almost defiant manner in which the paintings have been hidden from view – lend these works a powerful presence. The paintings can also be interpreted as a direct reference to Hammons’ race-based exclusion from the various ‘high’ art movements that he has witnessed in his long career, and the exclusionary milieu of the art world in general. Born in 1943, Hammons carved out his career in the aftermath of Abstract Expressionism, and experienced Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, conceptual art and appropriation, but all from the outside. This sense of being an ‘outsider’ was forcefully conveyed in an early work entitled Pissed Off (1981), which showed the artist urinating on a Richard Serra sculpture.

In Europe, Hammons’s work can be found in the collections of the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (Ghent), the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (Paris), the François Pinault Foundation (Venice) and Tate Britain (London). Important American collections include The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, The Fogg Art Museum, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, The Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, MOMA and The Whitney Museum of American Art, both in New York.

-----

David Altmejd, Roni Horn, Didier Vermeiren, Danh Vo

Untitled 1 (Spectres) and Untitled 3 (Spectres) form part of David Altmejd’s on-going series of sculptures that take the form of Plexiglas vitrines. These are broadly divided into two categories: monumental cases featuring intricate landscapes made up of hands and heads, cast fruit, thread and smashed mirrors, for example, and smaller vitrines typically containing arrangements of rare crystals and minerals. While Altmejd’s displays are reminiscent of those found in natural history museums, and are thus symbolic of order, classification and knowledge, they go beyond mere museological concerns. While the transparency of the cases encourages a closer inspection of the contents, the scale of the vitrines prevents the viewer from immediately grasping the whole. Only by walking around the sculptures, and by scrutinising them from every perspective – on a macro and micro level – is it possible to truly absorb the works in their entirety. And unlike museum displays, which typically aim to be encyclopaedic, Altmejd’s enigmatic ensembles are full of lacunae, including empty shelves (Untitled 1). Originally trained as a biologist, crystals feature extensively in Altmejd’s work. By placing them in vitrines, however, the objects become almost fetishized – but it is up to the viewer to decide which taxonomies, if any, underpin their seemingly idiosyncratic arrangement.

Roni Horn’s Two Pink Tons (D) is a two-part sculpture cast in solid glass which, depending on the light, or the position of the viewer, can be breathtakingly transparent or dramatically reflective. The matte sides are the result of the glass coming into contact with the surface of the mould, whereas the slightly concave tops were only exposed to the air during the casting process and have thus remained glossy. Looking down into them is like staring into pools of molten glass. Subsequently fire-polished, the transparent yet mirror-like surfaces of the sculpture confound the senses: Two Pink Tons (D) is both heavy yet apparently immaterial, solid but constantly changing, voluptuous but inherently cold and hard. In this sense, the sculpture is the materialization of mutability, a rendering of the potential for change – not just within matter, but also within our physical and spiritual selves. Another reading of the work would be to consider it in terms of gender: the rectangular forms, with their echoes of minimalism, might be perceived as ‘masculine’ while the delicate pink hues could be seen as ‘soft’ and ‘feminine’. Together, these qualities are suggestive of androgyny.

Didier Vermeiren belongs to a generation of artists who, since the 1970s, has been drawing on the legacy of conceptual art and minimalism. While Roni Horn’s Two Pink Tons (D) rests directly upon the gallery floor, Place is both plinth and sculpture. Vermeiren has been occupied with the history and specific nature of sculpture since the 1970s, more specifically the plinth. The fraught relationship between sculpture and pedestal is often viewed as a metaphor for the correlation of sculpture and reality – with Vermeiren subscribing to Brancusi’s belief that the plinth is integral to the work. Place is from a series of sculptures by Vermeiren that feature metal ‘cages’ on wheels. In this case, although the sculpture has wheels it does not stand on them. Rather, it balances on a plinth of equal proportions. Vermeiren: ‘If you stand in front of these works you can see that they do not completely conceal the floor underneath them. For me, it was always clear that a sculpture has a front, a back and various sides. The wheels give the work a forward and backward orientation and in this way they at once define and limit its sideways extension. The wheels are there and they indicate a movement, but the movement does not actually have to occur.’ While Vermeiren has often cited Rodin as a key modernist sculptor, his ‘wagon’ or ‘cage’ works refer explicitly to Giacometti’s idea that a sculpture is defined not just by the object, but also by the surrounding space.

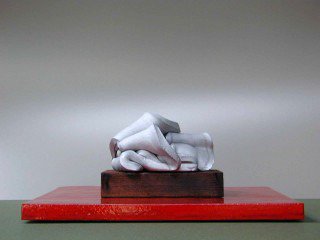

Solide plastique #4 is part of a series of works that was created in the late 1990s and which marked an important shift in Vermeiren’s oeuvre. In these works, Vermeiren explored ‘anti-form’: slabs of clay thrown on a plinth, with only gravity exerting some kind of impact on the material before firing. Highly sensual, these works have been described as ‘sculptural flesh’. The title, Solide plastique, refers to the transformation of clay – from soft and pliable during handling to hard and solid after firing. Clay, an essential yet ultimately invisible element of the classical sculptural production process, now becomes sculpture in its own right. In the Solide plastique series, Vermeiren illuminates the various relationships between body and mass, sculpture and plinth, form and mould, immobility and movement, as well as the position of the sculpture in space and its relationship with the spectator. Vermeiren: ‘But my subject is really about presence. The presence of what? The presence of my work, of my sculpture. Nature? It does not feature in my work. What could be there, what is actually present in my work, and what becomes visible in it, is the human body. Consequently, the sculpture has the measure of the body that has worked on it and made it. The body, yes, the human body.’

David Altmejd was born in Montréal, Canada in 1974. He lives and works in New York. Recent solo exhibitions include: Brant Foundation Art Study Center, Greenwich, CT (2011), Conte crépusculaire [Twilight Tale] at the Galerie de l’UQAM, Montreal, Canada, (2011) and Colossi at the Vanhaerents Art Collection, Brussels (2010).

Roni Horn was born in New York in 1955. She lives and works between New York and Reykjavik, Iceland. Recent solo exhibitions include: Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt am Main, Germany (2013), Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany (2012) and the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany (2011). Her work was the subject of a major retrospective in 2009: Roni Horn aka Roni Horn (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Collection Lambert, Avignon; Tate Modern, London; ICA – Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston).

Didier Vermeiren was born in Brussels in 1951, where he continues to live and work. Recent solo exhibitions include: Didier Vermeiren. Skulpturen, Skulpturenpark Walfrieden, Wuppertal, Germany (2012-2013), Etude pour le monument à Philippe Pot (1996-2012), Eglise de Saint-Philibert, Dijon, France (2012), Didier Vermeiren, La Maison Rouge, Paris, France (2012) and Didier Vermeiren. Sculptures, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium (2012).

Danh Vo was born in Vietnam in 1975 and brought up in Denmark. He currently lives and works in Berlin. He exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2013 and was the winner of the 2012 Hugo Boss Prize. Vo was awarded the BlauOrange Kunstpreis der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken in 2007 and was nominated for the Preis der Nationalgalerie für junge Kunst in 2009. Recently solo exhibitions include Go Mo Ni Ma Da at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris (2013), I M U U R 2 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (2013), Uterus at the Renaissance Society/University of Chicago (2012) and We The People (details) at the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen (2012).

Image: Didier Vermeiren, Solide plastique #4, 1999

Opening January 16, 5–8pm

Xavier Hufkens

6 rue St-Georges | St-Jorisstraat

Brussels

Open Tuesday to Saturday, 11 am to 6 pm