Paul Gauguin

dal 25/2/2014 al 7/6/2014

Segnalato da

25/2/2014

Paul Gauguin

The Museum of Modern Art - MoMA, New York

Metamorphoses. It's the first major monographic exhibition on Paul Gauguin (French, 1848-1903) ever presented at MoMA, and the first major exhibition to focus particularly on the artist's rare and extraordinary prints and transfer drawings and their relationship to his paintings and his sculptures.

Gauguin: Metamorphoses is the first major monographic

exhibition on Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903) ever presented at MoMA, and the first major

exhibition to focus particularly on the artist’s rare and extraordinary prints and transfer drawings

and their relationship to his paintings and his sculptures. Approximately 160 works, including

some 130 works on paper and a critical selection of some 30 related paintings and sculptures, will

be on view from March 8 through June 8, 2014, in The International Council of The Museum of

Modern Art Special Exhibition Gallery. Featuring loans from many different collections—national

and international, public and private—the exhibition offers an extraordinary opportunity to see

these works brought together. Many have rarely if ever been shown in the United States.

Gauguin: Metamorphoses is organized by Starr Figura, The Phyllis Ann and Walter Borten

Associate Curator, with Lotte Johnson, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints,

The Museum of Modern Art.

More than any other major artist of his generation, Paul Gauguin drew inspiration from

working across mediums. Though most often celebrated as a pioneer of modernist painting, at

various moments Gauguin was also intensely engaged with wood carving, ceramics, lithography,

woodcut, monotype, and transfer drawing—all mediums that ignited his creativity. Gauguin, who

had no formal artistic training, led a peripatetic life, settling for extended periods in different

regions of the world—including, most famously, Tahiti. His search for a culture unspoiled by

European mores and constraints paralleled his eagerness to work with unfamiliar techniques in

order to create entirely new types of artworks.

This exhibition focuses on these less well-known but arguably even more innovative

aspects of Gauguin’s practice, especially the rare and extraordinary prints he created in several

discrete bursts of activity from 1889 until his death in 1903. These remarkable works on paper

reflect Gauguin’s experiments with a range of mediums, from radically “primitive” woodcuts to

jewel-like watercolor monotypes and large, evocative transfer drawings that rank among the great

masterpieces in the history of the graphic arts.

Gauguin’s creative process often involved repeating and recombining key motifs from one

image to another, allowing them to evolve and metamorphose over time and across mediums. Of

all the mediums to which Gauguin applied himself, it was printmaking—which always involves

transferring and multiplying images—that served as the greatest catalyst in this process of

transformation. Gauguin embraced the subtly textured surfaces, nuanced colors, and accidental

markings that resulted from the unusual processes that he devised, for they projected a darkly

mysterious and dreamlike vision of life in the South Pacific, where he spent most of the final 12

years of his life. Through printmaking, Gauguin often sought to bridge the distinctions between

mediums. His woodcuts, for example, reflect the sculptural gouging of his carved wood sculptures;

his monotypes and transfer drawings combine drawing with printmaking.

In order to highlight the cross-fertilizing relationships among works across mediums in

Gauguin’s oeuvre, Gauguin: Metamorphoses is organized, roughly chronologically, into a number

of extended groupings of related works.

Zincographs: The Volpini Suite

In 1889, at the age of 41 and having only just reached stylistic maturity, Gauguin made his first

prints at the request of his dealer, Theo van Gogh. Named after the Café Volpini in Paris, where

the prints were available to view, this suite of 11 zincographs, all of which are included in the

exhibition, signals Gauguin’s boldly unorthodox and provocative choices. Creating his compositions

on zinc plates rather than the traditional limestone slabs used for lithography, he experimented

with unconventionally shaped compositions, details that extend beyond the picture borders, and

evocative textural passages. He printed them on vibrant yellow paper more commonly associated

with commercial posters.

Seven of the 11 Volpini compositions reinterpret paintings and ceramics inspired by

Gauguin’s recent trips to Brittany, Arles, and Martinique. Three of these highly inventive ceramics,

which Gauguin created between 1886 and 1888, will be shown alongside the Volpini Suite in the

exhibition. Cup Decorated with the Figure of a Bathing Girl (1887–88) and Vase with the Figure of

a Girl Bathing under the Trees (c. 1887–88) both explore the figure of a bather, whose crouching

pose is reprised in the related zincograph. The painterly textures and glowing colors that Gauguin

was able to develop in the process of firing and glazing are also evident in Vase Decorated with

Breton Scenes (1886–87), which features a group of young women wearing the region’s

distinctive traditional clothing. In the related zincograph, he simplified and abstracted the figures

to stark black lines and washes.

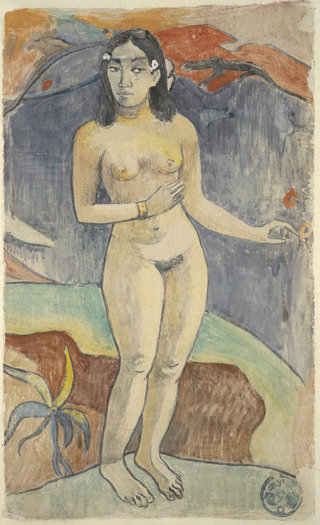

Woodcuts: The Noa Noa Suite and The Vollard Suite

A large portion of the exhibition is devoted to the groundbreaking series of works known as the

Noa Noa suite (1893–94)—Gauguin’s first woodcuts. Depicting Tahitian scenes, these 10 woodcuts

portray a grand life cycle encompassing primordial origins, everyday life, love, fear, religion, and

death. Most of the compositions are related to paintings and sculptures that Gauguin particularly

prized. For example, in the woodcut Nave nave fenua (Delightful Land), he developed the motif of

a Tahitian Eve from his earlier painting Te nave nave fenua (The Delightful Land) (1892),

rendering it more stylized and abstract, and reprised the subject in a watercolor monotype, in

which his Eve appears as an evanescent, sensual figure. All of these related works will be on view

in the exhibition, along with a full-scale charcoal and pastel study for the painting and a small

wood sculpture devoted to the same subject.

The Noa Noa woodcuts mark a turning point in the history of printmaking, ushering in the

modern era with their distinctly rough and “primitive” aesthetic. Gauguin approached his wood

printing blocks as a natural extension of the sculptural carving of his wood reliefs and sculptures,

and he experimented with a range of unusual effects in the inking and printing of each impression.

In order to highlight the relationship between sculpture and printmaking in his work, the

exhibition will include several of the woodblocks that Gauguin used to print the Noa Noa series,

alongside related wood sculptures and reliefs. The exhibition will also include several variant

impressions printed from each block, each of which represents a new experiment.

In 1898–99, having returned to Tahiti for the second and final time, Gauguin created a

second major series of woodcuts known as the Vollard Suite, after the Paris-based dealer,

Ambroise Vollard, to whom Gauguin sent the edition for sale. The complete series of 14 prints will

be on view in the exhibition. Most reprise figures and themes from Gauguin’s paintings and

sculptures made in Brittany, Arles, and Tahiti—serving as a condensed retrospective of his career.

When placed side by side, works from this suite create a series of vignettes similar to his

monumental paintings of the time, such as Faa iheihe (Tahitian Pastoral) (1898), which will also

be included in the exhibition.

Watercolor Monotypes

In 1894, around the time he was creating the Noa Noa woodcuts, Gauguin made another body of

unusual printed works: his watercolor monotypes. Monotypes were traditionally made with oil- or

water-based paint on a metal or glass surface and transferred to paper via rubbing or on a

printing press. Gauguin’s exact methods are not known, but it is believed that he either made

direct counterproofs of his watercolor, pastel, or gouache drawings on damp paper, or used

watercolor on glass to copy existing drawings or watercolors and then pulled an impression on

paper. Many of Gauguin’s monotypes are related to his paintings, sculptures, or woodcuts, while

others seem to be independent studies or sketches. The watercolor transfer process resulted in

images that are distinctly ethereal, suggesting ghostly afterimages, faded mementos, or beautiful

scenes viewed through the watery veil of memory.

Featured in the exhibition is one of the few surviving drawings that he may have used in

this process, Tahitian Girl in a Pink Pareu (1894), along with two of the three known monotypes of

the same of the same image.

Oil Transfer Drawings

Gauguin invented the oil transfer drawing technique in 1899, and it represents a grand

culmination of his use of printmaking to develop an aesthetic of mystery, indeterminacy, and

suggestion. A hybrid of a drawing and a print, each transfer drawing is a two-sided work with a

pencil drawing on the verso and the transfer drawing on the recto. In Gauguin’s words, “First you

roll out printer’s ink on a sheet of paper of any sort; then lay a second sheet on top of it and draw

whatever pleases you.” The pressure from the pencil caused the ink from the bottom sheet to

adhere to the underside of the top sheet. When the top sheet was lifted away, the drawing had

been transferred, in reverse, to its underside; this transferred image was the final work of art.

Using this transfer process, Gauguin transformed a traditional and usually legible pencil drawing

into a dark and mysterious print.

Gauguin’s transfer drawings, dating c. 1899 to 1903, range from small, sketch-like

examples to large, finished compositions. The exhibition includes several monumental, double-

sided transfer drawings; three of these, each titled Tahitian Woman with Evil Spirit (c. 1900), will

be shown alongside a remarkable related wood sculpture, Head with Horns (1895–97), reflecting

Gauguin’s preoccupation with the recurring theme of a Tahitian woman haunted by a mysterious

spirit.

Press Office

Paul Jackson, (212) 708-9593, paul_jackson@moma.org

Margaret Doyle, 212-408-6400, or margaret_doyle@moma.org

or (212) 708-9431 or pressoffice@moma.org

Press Preview: Wednesday, February 26, 2014, 10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m

he Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street, New York

Hours: Saturday through Thursday, 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Friday, 10:30 a.m.–8:00 p.m.

Admission: $25 adults; $18 seniors, 65 years and over with I.D.; $14 full-time students with current I.D. Free, members and children 16 and under.