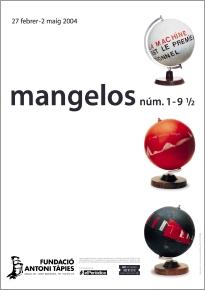

Mangelos

dal 27/2/2004 al 2/5/2004

Segnalato da

27/2/2004

Mangelos

Fundacio Antoni Tapies, Barcelona

While working as an art critic and museum curator in Zagreb, Dimitrije Basicevic adopted the pseudonym of Mangelos in order to develop his theories and create works of art that he himself did not consider to be art at the time. It is difficult to determine exactly when and how he began his work as an artist because his activities were kept strictly private until the mid-1960s. By moving from art to non-art, Mangelos created his own sphere of freedom, which allowed him to move in all directions

Curator: Branka Stipancic

Dimitrije Basicevic was part of the generation that grew up during the occupation of his country in the Second World War, at a time filled with violence, poverty, concentration camps and a collapse in morality. A generation whose schooling had to be interrupted and was restarted only after the war. In order to escape the imminent danger of the time, Basicevic left the country and fled to Vienna, where he studied art history, later returning to Yugoslavia, where he belonged to the resistance for a brief period. In 1949, Basicevic graduated in art history from the Faculty of Philosophy at Zagreb, where he also took a doctorate in 1957. While working as an art critic and museum curator in Zagreb, he adopted the pseudonym of Mangelos in order to develop his theories and create works of art that he himself did not consider to be art at the time. It is difficult to determine exactly when and how he began his work as an artist because his activities were kept strictly private until the mid-1960s. As he himself had accurately predicted, Dimitrije Basicevic Mangelos died in 1987 at the age of 66; in the shid theory manifesto, published and exhibited in 1978 in Zagreb, he divided his life into nine and a half ''Mangelos'', ending in the year of his death. In this manifesto, he referred to the ''biopsychological theory'' of which he had first heard mention when attending school in his native village of Sid. According to this theory, the cells of the human organism are completely renewed every seven years, thus giving rise in each human being to diverse and completely different personalities – Mangelos used it to explain the first and last works of various artists – Rimbaud, Van Gogh and Picasso – and of himself, classifying and dating his own works in accordance with the 9 and a half Mangelos into which he had divided his life. Mangelos No. 1 was a provincial boy, who lived in Sid; Mangelos No. 2 was a pupil at both primary school and high school; Mangelos No. 3 wrote poems in his note-books and paid tribute to the relatives and friends that had been killed in the war with black rectangles that he would later refer to as paysages de la mort and paysages de la guerre; Mangelos No. 4 registered his first alphabets in books that he had painted black and studied art history; Mangelos Nos. 5 and 6 were already deeply committed to art, painting tabulae rasae, paysages, anti-peinture, Pythagoras, nostories, etc. and participating in the work of the avant-garde group Gorgona, which was active in Zagreb between 1959 and 1966, and whose members based their radical projects on anti-art foundations. Mangelos No. 7, No. 8, No. 9 and No. 9_ formulated theories about art, culture and civilisation, writing them in brochures, as well as on cardboard panels and globes. Given that it is not easy to date Mangelos' works (he began exhibiting in 1968 and dated his works according to his biopsychological theory, sometimes with the date when the ideas came to him for the works and not always according to the moment when he produced them) this current exhibition has not been conceived as a chronological presentation of his works. It deals with various topics, such as ''war landscapes'', ''death landscapes'', ''Pythagoras'', ''alphabets'', ''words'', ''anti-paintings'', ''nostories'' and ''manifestos'', that Mangelos repeated throughout his life. According to the later periodisation made by Mangelos, his work begins in the post-war period with groups of works: ''death landscapes'', ''war landscapes'', ''landscapes'', ''tabulae rasae'' (monochromatic black and white surfaces with text written underneath), which he used to express a state of forgetfulness and the beginning of a fresh start. Writing on these clean slates corresponded, on the one hand, to a desire to start from scratch and, on the other hand, to an attempt to deny painting. Using the anti-art positions of the Gorgona group, Mangelos denied painting, accentuating the rational factor in art. Later, he wrote ideas, poetry (''nostories'') and manifestos in black, white and red, in calligraphy between lines, in a hybrid form of writing and painting in note-books, on wooden boards and globes. In his attempt to deny painting and to fight its irrational side, Mangelos painted letters from different alphabets, ending up by geometrising them and transforming them into abstract paintings, in which the characters sometimes became unrecognisable and, as he himself stated with some humour, reached the point of incoherence. Mangelos frequently resorted to glagolithic letters. The glagolithic alphabet was introduced into the Slav language communities from the end of 9th century and used to write down the Slav liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church. He also denied painting through the use of other techniques, such as the ''anti-painting'' series, in which statements such as negation de la peinture, antipeinture or nopainting are written on reproductions of paintings that have had black lines drawn over them or been painted in black. Mangelos was engaged in a dialogue, or rather a discussion, with everything that he studied, and his interests were wide-ranging, from philosophy and art to psychoanalysis and biology. He wrote manifestos on paper, cardboard panels, globes and brochures, in which he touched upon a wide variety of questions. The main hypothesis that cuts across all the manifestos is that society has progressed, but that art has been left behind. Mangelos did not believe in an art existing beyond the progresses of the modern world. Many manifestos encapsulate the idea of two civilisations, the manual civilisation and that of the machine, the former being based on the ''old ingenuous and metaphorical way of thinking'' and the latter on ''functional thinking''. The texts were a specific way of expressing highly subjective statements, dominated by the theory of the ''machine civilisation'' and ''functional thinking'', with which he asserted his theories about the development of society and the non-development of art, or, in other words, about the crisis and death of art. Humour and irony were always present in his work – in the expounding of thoughts, in the discrepancy between the pretentious message and the banal phrase, in the scorn shown for authority, mixing together different foreign languages, in particular German, French and English. In addition to the major and important themes of evolution, history, consciousness and truth, Mangelos touched upon trivial, everyday matters; for example, he wrote a manifesto about his dog Alpha (manifesto about alpha).

Characteristically, in his works on paper, Mangelos always used pre-printed material – maps, pages torn from books, dust covers, exhibition catalogues or books – which he covered with paint to serve as a support for his own work. His works therefore seem to have a double life: a first one that is hidden beneath the paint and another one that is given to them by the artist.

Devising his own individual language and his own rules, ignoring conventions and waging a permanent battle against himself and others, Mangelos is a truly avant-garde figure, who points the way to a new understanding of art. By moving from art to non-art, Mangelos created his own sphere of freedom, which allowed him to move in all directions. Although Mangelos, in his modesty, attached little importance to this, his non-art is the search for a path beyond that of preconceptions, beyond what is known.

Organization:

This touring exhibition has been organised by Fundação de Serralves, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto, and co-produced by Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz, Fundació Antoni Tà pies, Barcelona and Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel. The exhibition is organised with the collaboration of El Periódico de Catalunya.

SPECIAL EVENTS

Dimitrije Basicevic (Sid, 1921 - Zagreb, 1987) was an art historian, critic and curator of exhibitions at galleries in the city of Zagreb. At the same time, although less well known in this regard, he was an artist who worked under the pseudonym of Mangelos (the name of a village near his birthplace, Sid).

Fundacio Antoni Tapies

Arago' 255 08007 Barcelona

Hours: From Tuesday to Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Closed on Mondays, except holidays.

It is necessary to make an appointment for group tours. Admission to the Fundació Antoni Tà pies until 15 minutes before closing.