Oteiza: Myth and Modernism

dal 7/10/2004 al 23/1/2005

Segnalato da

7/10/2004

Oteiza: Myth and Modernism

Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao

A retrospective: 140 sculptures, 43 drawings and collages

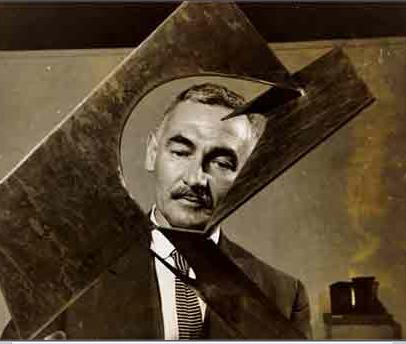

Oteiza: Myth and Modernism is the most comprehensive retrospective of the work of Jorge Oteiza to have been presented in the last 15 years. Curated by Margit Rowell and Txomin Badiola, the exhibition features some 140 sculptures borrowed from museums and private collections as well as more than 43 drawings and collages from the Fundación Museo Jorge Oteiza, shown here in public for the first time. Arranged to follow the artist’s experimental progress and to capture his formal and conceptual evolution, Oteiza: Myth and Modernism fills four uniquely shaped galleries on the third floor of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Oteiza is unquestionably one of the leading Basque artists of the 20th, although exhibitions of his work have been few and far between. Highly personal and quite unlike the work of any other artist of his generation, his art is difficult to define. While in retrospect his later works appear related to American Minimalism —a movement that emerged after the Basque artist’s creative career had effectively ended—Oteiza’s sculptures are rooted in the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century: Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism, Neoplasticism, and Constructivism in particular. What Oteiza shares to a great extent with other artists of the postwar period is a sensibility that may be defined as abstract, spiritual, and humanist.

Oteiza was born in Orio, Guipúzcoa, in 1908. After studying medicine for three years in Madrid, he attended the city’s School of Arts and Crafts, during which time, under the influence of Jacob Epstein, Dimitry Tsaplin, and Alberto Sánchez, he produced his earliest sculptures, later exhibited in Madrid. In 1931, his sculpture Adam and Eve, Tangent S=E/A (Adán y Eva, Tangente S=E/A) won first prize at the ninth Guipúzcoa Competition for New Artists.

Oteiza’s first sojourn in Latin America, from 1935 to 1948, was a crucial event in his life. He exhibited in Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires while also teaching and researching ceramics, first in Buenos Aires and later in Bogotá. He published “Carta a los artistas de América. Sobre el arte nuevo en la posguerra†(“Letter to the Artists of America: About New Art in the Postwar Periodâ€) at this time and gave lectures to publicize his aesthetic theories and sources, including “Informe sobre una estética objetiva (fórmula molecular, ontologÃa, para el ser estético)†(“Report on an Objective Aesthetic [Molecular Formula, Ontology, in Relation to the Aesthetic Being]â€) and “La investigación de la estatuaria megalÃtica en América†(Research into Megalithic Statuary in America). These, like the works executed on his return to Bilbao in 1948, bear witness to Oteiza’s development, forming the foundation for what was to be the most important phase of his career, his Experimental Purpose (Propósito experimental) period.

Throughout the 1950s, Oteiza’s work earned increasing recognition at home and abroad. In 1950, Triple and Lightweight Unit (Unidad triple y liviana) marked the beginning of his experimentation with “the aesthetic nature of the statue as a purely spatial entity.†In the same year, he began work tentatively on a major commission for the statuary of the basilica at Aránzazu, a huge undertaking finally realized in 1969. Here, religious motifs are depersonalized; figures are emptied, opened to space, and filled with spiritual content.

In 1955, Oteiza began to explore the treatment of light, creating hollows, orifices, and perforations —dubbed “light condensers†by the artist— first in reliefs and later in freestanding forms. In works such as Homage to Boccioni (Homenaje a Boccioni, 1956–57), these orifices allowed light to reach the interior of the sculpture, endowing it with energy. He also continued to experiment with small blocks of stone, using a disk saw to make a series of cuts in order to reveal the stones’ inner structure. These Disk-cut Stones (Piedras discadas) are witness to Oteiza’s desire to open up his polyhedra.

By 1956, Oteiza was seeking a new vocabulary that would enable him to take the experimental in sculpture to its most radical degree. To do this, he defined a series of open formal units that together would forge an entirely new language. In 1956 and 1957, these units provided the basis for new experimental series. Among the earliest creations in these series are some of his most important sculptures, including Homage to Malevich (Homenaje a Malevich, 1957) and the maclas works.

In 1957, Oteiza received the International Sculpture Award at the fourth São Paulo Bienal for twenty-eight sculptures presented in experimental “families.†He also published Propósito experimental, 1956–57, in which he set out the theoretical principles of his art. After São Paulo, Oteiza began to think deeply about the increasing role played by the void and silence in his sculptures. At this time, he formulated the ley de cambios (law of changes), according to which “one always starts from a nothing that is nothing to arrive at a Nothing that is everything.â€

A brief period followed, lasting barely two years (1958–59), in which Oteiza executed sculptures inspired by his recently formed principles. His Empty Boxes (Cajas vacÃas) and other works involving the “emptying of the cube†most faithfully represent the conclusions of his experiments. They also led to his most radically pre-Minimalist works, such as Homage to Velázquez (Homenaje a Velázquez, 1959). Having finally related the void he increasingly found in his work to the spiritual emptiness of prehistoric Basque cromlechs, Oteiza arrived at “the experimental conclusion that sculpture can no longer be associated, as expression, to man or the city.†Consequently, in 1959, he abandoned his activity as a sculptor.

During the 1960s, Oteiza devoted himself entirely to aesthetic and linguistic research, particularly in the field of Basque culture. He became actively involved in the political and social causes of the Basques and wrote at length about such issues, as in the books Quousque tandem! (1963) and Ejercicios espirituales en un tunel (Spiritual Exercises in a Tunnel, 1965). Between 1972 and 1975, he returned to sculpture to complete some of his earlier experimental series.

During the 1980s, Oteiza’s work at last began to receive the attention it deserved. A range of institutions, including the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina SofÃa in Madrid, the Fundacio Museu d’Art Contemporani in Barcelona, and the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao, began to acquire his works in depth. In 1986, for the first time in twenty-five years, works by Oteiza were included in an international exhibition of sculpture, Qu’est-ce que la sculpture moderne? at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Still, Oteiza’s work remained relatively unknown until 1988, when a major retrospective was organized by the Fundación Caja de Pensiones in Madrid, Bilbao, and Barcelona. This exhibition allowed public audiences and critics alike to appreciate his vast artistic legacy for the first time. In the same year, his work was featured in the Spanish pavilion at the VeniceBiennale, accompanied by works by Susana Solano.

Exhibition organized by the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao with the collaboration of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina SofÃa