Aernout Mik / Rhizome

dal 22/6/2005 al 10/9/2005

Segnalato da

22/6/2005

Aernout Mik / Rhizome

New Museum Chelsea, New York

Refraction, the most recent video installation by A. Mik, is an enigmatic portrait of the social body as it responds to a disaster. His approach is unusual in that the projection surface tends to be positioned quite aggressively within the viewing space, as an extension of the architecture itself. Rhizome ArtBase 101 surveys salient themes in Internet-based art-making. The show presents forty selections from Rhizome.org's online archive of new media art, the ArtBase, which was launched in 1999 and currently holds some 1500 works by artists from around the world.

Aernout Mik. Refraction

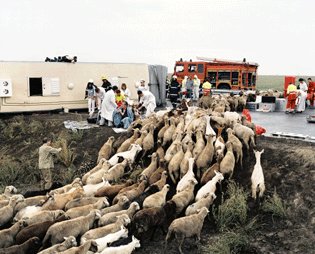

Refraction, the most recent video installation by Dutch artist Aernout Mik, is an enigmatic, occasionally cryptic portrait of the social body as it responds to a disaster. Some of the participants are actively engaged in controlling the scene, others are passive spectators, while still others are conspicuously absent - the supposed victims of this bus crash. And then there are the sheep and pigs.

Although Mik's work emerges from a distinguished tradition of video installation, his approach is unusual in that the projection surface tends to be positioned quite aggressively within the viewing space, as an extension of the architecture itself. Entering Refraction, the first thing to strike our attention is the long, "broken" wall that serves as the projection surface for the 30-minute film. Like most everything in Refraction, the wall is an oblique reference to a kind of upheaval, an ongoing distortion whose psychological counterpart is the peculiarly detached, even robotic conduct of the characters involved in the rescue scene.

For an earlier work, Organic Escalator (2000), the surrounding walls are rigged to slowly move the projection screen closer and closer to the viewer, making it seem as if the disaster depicted within the work is steadily drawing nearer. Similarly, when Middle Men (2001) was first presented as part of the Yokohama Triennial, Mik installed it as a rear-projection kiosk inside a shopping mall, so that the resulting image - a post-stock market crash meltdown on a trading floor - might be more easily mistaken for a news broadcast or even a marketing tool.

Mik's interest in scenes of disaster is not about envisioning violence. This may be why, despite the relative sophistication of his video productions, he does not go to great lengths to convince us that what is happening onscreen is actually real. In fact, part of the anxiety that Mik's work provokes comes from the continuous disconnect, which never gets resolved, between each individual's thoughts and actions and his or her way of behaving within a larger group.

In Middle Men, no one makes any attempt to interact with his neighbor: a few keep on working, but most sit and stare blankly into space, with only an occasional involuntary spasm or twitch of the body to suggest that the cataclysm has penetrated the human nervous system itself. Likewise, in the multiple-projection work Reversal Room (2001), which explores in elaborate detail and from several angles a physical attack on a waiter in a Chinese restaurant, everyone in the immediate vicinity behaves as if nothing at all were taking place. They eat their meals and continue their conversations, oblivious to the apparent force with which the waiter restrains his attacker by hurling him onto a nearby table.

During the course of Refraction, a strange ennui hangs over each individual, from emergency personnel to stranded motorists, and this disaffection begins to dominate whatever action there is. Nobody speaks or interacts meaningfully with anyone else, no overt displays of emotion take place, and even the most tightly interwoven group movements unfold numbly, in a strange buffer zone of interpersonal distance.

Mik reveals to us that, as a society, we have become so deeply accustomed to social barriers that we no longer know how to participate in activities and events that are not staged for us. This is not to argue that respecting civil authority in emergency situations is a bad thing, or that personally trying to assume control over an ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES

New Museum of Contemporary Art

210 11th Avenue 2nd Floor NYC 10001 unmanageable crisis is a good thing. But for Mik, these depictions of faux crisis, which contain just enough reality to hold our attention, are intended to point out the increasingly universal experience of indifference toward one's fellow human beings. Not only are we pulling apart from one another - despite the mechanisms of globalization - but our failure to stay connected results in a lessening of each individual's own capacity for self-preservation. For without the ability (and empathy) to recognize that one's neighbors' lives (and those of far-distant strangers) are as valuable to them as ours are to us, human life in general starts to seem like an abstraction. In our desire to wake up Mik's characters and snap them into fully recognizing their place in the world lie the seeds of our own confusion about how much we want to get involved, how to break out of our shells, and how to behave as if our neighbor's fate is inseparable from our own.

Aernout Mik: Refraction is part of the Three M Project, a series by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York to commission, organize, and copresent new works of art. Generous support for the series has been provided by the Peter Norton Family Foundation and the American Center Foundation.

Refraction also received support from the Mondriaan Foundation, Amsterdam, and The Consulate General of The Netherlands in New York.

---

Rhizome ArtBase 101

RHIZOME ARTBASE 101 surveys salient themes in Internet-based art-making, a practice that has flourished in the last ten years. The exhibition presents forty selections from Rhizome.org's online archive of new media art, the ArtBase, which was launched in 1999 and currently holds some 1,500 works by artists from around the world. Featured works are grouped by ten unifying themes and include seminal pieces by early practitioners as well as projects by some of the most pioneering emerging talents working in the field today. Encompassing software, games, moving image and websites installed on computers or elaborated in installations, Rhizome ArtBase 101 presents the Internet as a strapping medium that rivals other art forms in its ability to buttress varied critical and formal explorations.

A number of projects respond to E-COMMERCE by disturbing online consumption, often through satire and emulation. Portland-based artist damali ayo riffs on the commodification of identity in rent-a-negro.com (2003), a service that offers the companionship of an African American person for a price but free of the commitment of "challenging your ownwhite privilege." RTMark, a brokerage firm of international artists, supports initiatives that sabotage corporate products and protocol through their headquarters, rtmark.com. British duo Thomson and Craighead provide a counterpoint to such direct engagements of capitalist enterprise in dot-store (2002), a line of goods that investigates the historical overlap between individual expression and commercial communication systems.

With cutting edge graphic interfaces and dependence on a player, GAMES provide rich terrain for artistic intervention. Works, like Sheik Attack (1999) by Israeli-born artist Eddo Stern, recontextualize game narratives to reveal the social and political agendas embedded in their structure. Modification, whereby artists hack into virtual worlds to alter their landscape or action, is a form of game art that echoes the equally interventionist traditions of graffiti and tagging. In Adam Killer (2000), Los Angeles-based artist Brody Condon restricts the first person capability of the player to killing and destruction only.

Although historicizing an emerging art practice is never simple, there are some landmark works that undoubtedly established a critical and formal context for Internet art practices as we see them today. EARLY NET.ART, represented in the ArtBase chiefly by European artists active in the mid to late 1990s, include such classic projects such as _readme (1998) by Heath Bunting and Desktop Is (1997) by Russian artist Alexei Shulgin. The latter project effectively reframed the computer desktop as a formal platform by aggregating artists' varied experiments with the basic computer interface. By exploring these very different "desktops," we can see how Internet artists were able to work online in an individualistic mode while at the same time operating in the context of an artistic community that was launching new projects using the Web and e-mail.

The Internet has provided a platform for exploration, action, and protest by artists who create works under the rubric of CYBERFEMINISM. American artist Prema Murthy plays with the "goddess/whore" paradigm in Bindigirl (1999). In this work, which parodies South Asian cyberporn sites, a character called Bindi speaks of the failure of new technologies to liberate her from constricting religious and gender identities. In another classic and pioneering work, Brandon (1998), whose source material is the true story of Tina Brandon, nomadic artist Shu Lea Cheang represents the paranoia and distrust around transgendered bodies by deploying graphic imagery and details across multiple screens and in diverse international locations.

SOFTWARE ART takes generative processes and code as its main source material, examining these as cultural forms rather than merely neutral sets of command sequences. Many software art projects interrogate the mechanisms of control that underlie software by destabilizing rote experiences of computing. Through its open source, cross-platform design the early program The Web Stalker (1997) by British collective I/O/D prompted a consideration of how commercial software limits options and experimentation. Conversely, theBot (2000) by American artist Amy Alexander downplays functionality in order to visualize certain operations that software enables, such as searching and rendering images.

DATA VISUALIZATION AND DATABASES manifest relationships between informational entities that might otherwise remain invisible or even unthinkable. Created using RSG's network surveillance program Carnivore (2001-2003), Los Angeles-based programmer Mark Daggett's Carnivore Is Sorry (2001) tracks users as they navigate the Web, then compresses the sites they visited into an abstract, data-dense jpeg and e-mails it to them. Databases have been employed to reorganize existing arrangements into new narratives or situations. One Year Performance Video (akasamhsiehupdate) (2004) sources prerecorded clips of Brooklyn-based artists M. River and T. Whid of MTAA into a streaming video diptych that simulates a fictional narrative of the artists living in adjacent, identical white cells for the duration of a year.

Artists interested in ONLINE CELEBRITY enlist personal platforms like blogs and homepages, and the gossipy, reflexive nature of the Internet, to transform personal behavior into public spectacle. On Marisa Olson's American Idol Audition Training Blog (2004), the San Francisco-based artist exhaustively documents the pitfalls and nervous anticipation involved in her attempt to become the next American Idol. In Diary of a Star (2004), Los Angeles-based artist Eduardo Navas re-contextualizes selections from The Andy Warhol Diaries (edited by Pat Hackett) to connect this earlier artist's legendary self-awareness to the attitudes of today's online personas. Embedded within layers of metadata and links, each diary entry's potential to spread across net appears infinite.

Aided by the proliferation of wireless technologies, new media artists encode, decode and scramble PUBLIC SPACES through electronic networks. In the audio storytelling project [murmur] (2003) by Canadian artists Shawn Micallef, James Roussel, and Gabe Sawhney, pedestrians can dial into a central database to share or hear location-specific stories about the area they are calling from. For Nike Ground (2003), the international team of artists known as 0100101110101101.org employed Internet-based marketing strategies (Web sites, e-releases) to fool the city of Vienna into believing that their beloved Karlplatz had been acquired by Nike and was to be supplanted by a monumental Swoosh.

NET CINEMA puts film and video in dialogue with digital aesthetics such as hypertext, databases, and algorithms. SUPER SMILE (2005) by Korean-based duo YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES, evokes multiple film genres - romance, action, noir  through the rhythm and pace of its experimental, text-based narrative. The flourishing of commercial media programs such as Flash in recent years has seeded new possibilities for moving image online. Still, some artists are more interested in a program's vulnerabilities than in its options. For his series Data Diaries (2003), New York artist Cory Arcangel tricked QuickTime into reading his daily desktop debris (old e-mails, jpegs, and Word documents) as media files, a maneuver that produced dozens of mesmerizing and abstract streaming videos.

Projects described as DIRT STYLE appropriate graphic detritus from the Web in gestures that both celebrate and satirize digital pop culture. In extreme animalz: the movie: part 1 (2005) by U.S.-based collective Paper Rad and Pittsburgh-based artist Matt Barton gif files of animals, sourced through Google's Image Search, are woven into a digital tapestry that is mirrored by a surrounding cluster of mechanized stuffed animals. Dirt Style works often express nostalgia through repurposing analog technology. In Dot Matrix Synth (2003), American artist Paul Slocum reprogrammed a dot matrix printer so that it plays electronic notes in accordance with different printing frequencies.

Rhizome ArtBase 101 is organized by Lauren Cornell and Rachel Greene with assistance from Kevin McGarry for Rhizome.org.

Rhizome.org receives support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, the Greenwall Foundation, the David S. Howe Foundation, the Jerome Foundation in celebration of the Jerome Hill Centennial, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, PubSub Concepts, Inc. and the members of Rhizome.

Media Lounge exhibitions and public programs are supported by Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Jerome Foundation in celebration of the Jerome Hill Centennial, and the New York State Council on the Arts.

---

The New Museum of Contemporary Art receives general operating support from the Carnegie Corporation, the New York State Council on the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, JPMorgan Chase, and members of the New Museum.

Image: Aernout Mik, Refraction (2005). Photographs: Florian Braun, Berlin. Images courtesy of Aernout Mik; carlier l gebauer, Berlin; and Projectile Gallery, New York

New Museum of Contemporary Art

556 West 22nd Street

New York