Barbed Wit: Italian Satire of the Great War

dal 9/1/2007 al 17/3/2007

Segnalato da

9/1/2007

Barbed Wit: Italian Satire of the Great War

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London

36 highly-coloured original designs by little-known artists will be on display from the archives of the Imperial War Museum, London. These large-scale drawings will be exhibited alongside a selection of corresponding monochromatic postcards so that the visitor can see the mass-produced outcome beside the original design.

Artwork for postcards produced in Italy during the Great War

Barbed Wit: Italian Satire of the Great War, on view at the Estorick

Collection of Modern Italian Art, 39a Canonbury Square, London N1, from

Wednesday 10 January to Sunday 18 March 2007, presents rarely viewed

original artwork for postcards produced in Italy during the Great War. The

exhibition displays bold designs, biting satire, and a specifically Italian

slant on wartime propaganda.

Thirty-six highly-coloured original designs by little-known artists will be

on display from the archives of the Imperial War Museum, London. These

large-scale drawings will be exhibited alongside a selection of

corresponding monochromatic postcards so that the visitor can see the

mass-produced outcome beside the original design. Postcards first appeared

in Austria from 1869 and became increasingly popular across Europe and

America reaching a ‘golden age’ in the first decade of the 20th century.

They could be printed inexpensively in black and white, to appeal and be

rapidly distributed to a mass public. In addition to the newspapers of the

day, postcards formed an important part of the social and political

commentary on events of the Great War and today they are an important source

of wartime ephemera.

At the outbreak of the Grande Guerra (Great War) in 1914, Italy formed part

of the Triple Alliance, together with Germany and Austria-Hungary, but

argued that an aggressive war did not uphold the terms of the alliance.

Both sides offered land to Italy in exchange for support but she initially

retained her neutrality. This hesitancy to declare an alliance is

satirised in Virgilio Retrosi’s shrewd image of a red-faced Italian

infantryman who ponders whether to follow a signpost to the ‘European

Theatre’. The title of the piece aptly sums up Italy’s dilemma: ‘Shall I

just be an extra or take a starring role?’. The prolonged

vacillation is amplified in another of Retrosi’s works ‘To go or not to go’

which depicts a young woman picking petals off flowers in a universally

recognised, but irrational, method of decision-making.

The Italian Futurists, since their foundation in 1909, had glorified and

advocated participation in war, defining it in their founding manifesto as

‘the sole hygiene of the world’. At the outbreak of World War I, Italy was

divided into neutralists and interventionists with the Futurists vehemently

supporting the latter movement through art and declarations, such as

‘Futurist Synthesis of the War’ and Giacomo Balla’s manifesto ‘The

Anti-neutral Suit’of 1914. In Giulio Gigli’s postcard design he imitates

the style of another Futurist, Gino Severini, in a semi-abstract, dynamic

composition, which merges the national colours of France, Belgium and

Germany, together with bullets, shrapnel and interspersed wording such as

‘misery’ and ‘snow’. The subtitle of this design ‘Dynamic Vision of Befana’

highlights the artist’s prediction of a miserable epiphany for those

countries already involved in the war .

Following the secret Treaty of London in April 1915, Italy, having secured

territorial gains, joined the Triple Entente and officially declared war

against Austria-Hungary on 23 May 1915. Artists used postcards to criticise

the actions or inaction of various sectors of the Italian people during the

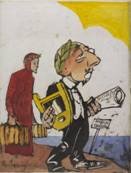

war. The prosperous bourgeoisie were typified as materialistic

war-profiteers who lacked patriotic duty. In ‘I have given a lot’

and ‘The Complaining Citizen’, the artist shows his disdain towards

an uncom-mitted and indifferent class, characterised here by a plump,

overdressed Boulevardier.

The designs, whilst demonstrating cutting satire, also show theatrical good

humour in their caricatures of key figures. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II is

depicted as Medusa (fig. 6) whilst Vittorio Emmanuele III is shown in ‘Armed

Neutrality’ as a diminutive figure peeping out of an excessively armoured

suit yet shackled by the chains of indecision. The country’s

flamboyant nationalist poet Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863-1938) was responsible

for a daring propaganda stunt during 1918 when, flying an aeroplane over

Vienna, he scattered red, white and green tinted postcards appealing to the

Viennese to turn on their government. This feat is referred to in Ferro’s

design of 1918 where he cunningly uses a quote from Dante

Alighieri, d’Annunzio’s historical counterpart, Poveri versi miei gettati al

vento (‘My poor verses have been scattered to the wind’).

The artists featured in this exhibition used a variety of different

satirical devices including personification, caricature and bestialisation

to create a sophisticated, shrewd and visually appealing commentary on

Italy’s involvement in the Great War.

The exhibition has been organised in collaboration with the Imperial War

Museum, London. A fully illustrated catalogue will be available with an

essay by art historian Nadia Marchioni (curator of the exhibition La Grande

Guerra degli artisti at Museo Marino Marini, Florence in 2005/6).

Press office:

Sue Bond PR

Hollow Lane Farmhouse, Thurston, Bury St Edmunds

Suffolk, IP31 3RQ Tel: +44 (0) 1359 271085 info@suebond.co.uk

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art

39a Canonbury Square - London

Opening hours: Wednesday to Saturday 11.00-18.00 hours, Sunday 12.00-17.00 hours

Admission: £3.50, concessions £2.50.