Islam in Africa

dal 8/10/2007 al 25/10/2007

Segnalato da

8/10/2007

Islam in Africa

Sam Fogg Ltd, London

The exhibition showcases the diversity and richness of the Islamic art of Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa. The first of its kind in the UK, the show includes art objects and manuscripts from African Islamic traditions that have been almost entirely overlooked by major collections.

An Exhibition of Works from Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa

Sam Fogg will hold a groundbreaking exhibition Islam in Africa at his

gallery at 15d Clifford Street, London W1, from Tuesday 9 to Friday 26

October 2007. The exhibition will showcase the diversity and richness of

the Islamic art of Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa. The first of its kind in

the UK, the exhibition will include art objects and manuscripts from African

Islamic traditions that have been almost entirely overlooked by major

collections.

East Africa

In East Africa, Islam spread along the trade routes that connected the coast

of Africa with the Arabian Peninsula and India. Arab merchants established

settlements as early as the 10th century, which grew into cosmopolitan

mercantile states such as Mogadishu, Barawa, Mombasa, Malindi, Kilwa and

Zanzibar. The arrival of the Portuguese at the end of the 15th century

heralded the decline of the city states; the Portuguese sought to divert the

trade, and during the course of the 16th century succeeded in establishing

political and mercantile hegemony. This only came to an end at the turn of

the 18th century when the Omani sultanate succeeded in ousting the

Portuguese from Mombasa and all the remaining coastal cities to the north.

Omani control was sporadic, and for much of the 18th century the city states

were de facto independent while recognising the authority of the Ottoman

Sultan. In the first half of the 19th century Sultan Sayyid Sa'id

re-established Omani control over much of coastal East Africa and in 1840

transferred his capital to Zanzibar, which eventually became the seat of an

independent sultanate.

The Sultanate of Zanzibar presided over a lucrative trade in cloves and

other African raw goods, particularly ivory. The influence of the British,

who were sailing to India round the African coast and were keen to protect

their maritime and mercantile interests from the Germans, was on the

increase. It was from Zanzibar that the explorer David Livingstone started

his second African expedition to search for the source of the Nile. A

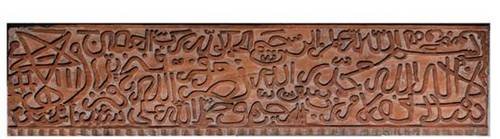

spectacular wooden panel, inscribed with Qur'anic verses intended to ward

off malign influences, by repute came from Livingstone's house there (fig.

1). Such panels, as well as carved doors, are a distinctive feature of the

architecture of Stonetown, Zanzibar's capital.

Islam also spread along the trade routes through the plains below the

Ethiopian highlands that brought slaves from the interior to the coastal

cities. Until the middle of the 16th century the Ethiopian plains were home

to a cluster of sultanates that resisted and threatened the Abyssinian

Empire. After the defeat of the greatest of these, the Adal Sultanate, at

the hands of a joint Portuguese-Abyssinian army in 1543, the Islamic

presence in Ethiopia for the next three centuries was restricted almost

entirely to the city of Harar. The city was the site of an independent

emirate from the middle of the 17th century and resisted incorporation into

the Abyssinian Empire until 1887.

From the early years of the Harari Emirate is a beautifully copied and

illuminated Qur'an, dated 1773, in its original distinctive Harari binding

(fig. 2). Very few such early East African Qur'ans have survived. Like the

other examples, this Qur'an is in a bold angular script with a commentary

that zig-zags across the margins of the pages. These features recall the

so-called 'Bihari' Qur'ans of 15th and 16th century North India and pose

fascinating questions concerning cultural transfer between India, South

Arabia and the East African coast.

Other items from Harari culture include wooden boards inscribed with verses

from the Qur'an (figs. 3 & 4). Qur'an boards, found across the whole of

Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa, were used as a means of teaching the Qur'an.

Once the pupil had finished inscribing the verses, the surface of the board

would be wiped clean. Some examples, though, are permanently inscribed and

bear talismans, constituting another of the many examples of the blend of

sacred text and ritual object that make sub-Saharan Islamic culture

particularly rich in tangible forms of worship.

West Africa

Following the Islamic conquest of North Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries,

Islam spread down the west coast of Africa along the trade routes that

brought salt, slaves and, above all, gold, to the Mediterranean and beyond.

Conversion began immediately among the Berber and African tribes that lived

in the regions surrounding these routes, and in the medieval period Islam

became the official religion of several great African trading empires such

as the Mali and Songhay Empires in the Western Savannah, and the Kanem and

Bornu Empires in Chad and Western Nigeria. Islam was taken up by the Hausa

people of Northern Nigeria and Niger as early as the 11th century, though

conversion was very gradual and Islamic practices often sat alongside

indigenous beliefs. The only partial conversion of the Hausa people,

especially in the countryside, provided some of the ideological impetus for

the foundation of an empire by the Fulani people, who led a series of jihads

throughout the region in the early 1800s.

Despite the longstanding presence of Islam in Saharan and sub-Saharan

Africa, very few manuscripts dating from before the 18th century have

survived outside libraries in Islamic centres such as Timbuktu. During the

17th and 18th centuries, a distinctly West African style of manuscript

copying and illumination emerged, marked by bold geometric decoration in

earth colours and the use of a distinctive variation of the North African

Maghribi script, often called 'Sudani', from the Arabic word for the region

'al-Sudan', or 'Land of the Blacks'.

The exhibition includes several manuscripts showing the development of the

Western Sudani style through the ages. An early example is an 18th century

copy of the medieval Spanish author al-Kala'i's Life of the Prophet (fig.

5). The most striking feature of the manuscript is the numerous full-page

illuminated panels filled with a variety of patterns in ochre, yellow and

red. The ingenuity of the designs makes this manuscript a showcase for the

marriage of the Islamic tradition of geometric decoration and the West

African genius for pattern.

A further development of the tradition is seen in a costly and pristine 19th

century copy of al-Jazuli's pilgrimage manual, the Dala'il al-Khayrat (fig.

6). Similar in format and design to the Life of the Prophet, the

illuminated panels and lettering are brighter and make use of brilliant

green. The quality of the script and illumination is matched by the superb

leather binding with tooled decorative patterns, and a marvellous carrying

case decorated with designs made from different coloured pieces of leather.

Representing the very culmination of the tradition is an early 20th century

printed Qur'an, the large, abstract and very bold patterns of which are the

fullest and most colourful expression of Hausa Qur'anic illumination (fig.

7).

The Saharan fringes of the Sudan are represented in the exhibition by a

magnificent 19th century Berber minbar (pulpit), probably from the Atlas

region (fig. 8). With its original polychrome and over a metre and a half

high, this is a splendid illustration of a North African Islamic tradition

rendered in a distinctive and colourful local idiom. The minbar was

acquired from a Paris jewellers, where it had been since the 1960s.

Opening 9 october 2007

Sam Fogg

15d Clifford Street, London

Free admission