Laurina Paperina

dal 23/1/2008 al 23/2/2008

Segnalato da

23/1/2008

Laurina Paperina

Siemens Art Lab, Wien

"At first glance one might think that we could place L. Paperina's work within the developing frame work of cartoons. The cartoon has taken the route of undermining its most consolidated narrative themes, which were determined by the intent to educate the children." (G. Bartorelli)

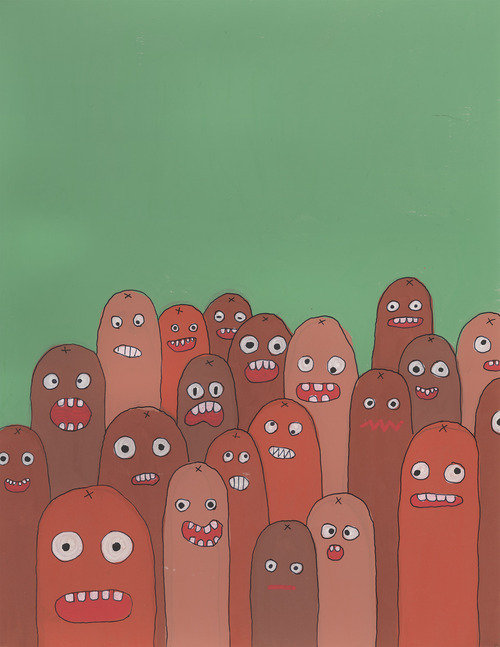

At first glance one might think that we could place Laurina Paperina's work within the developing frame work of cartoons. Since 1989, the date in which the pioneering Simpsons and the cartoon within it Itchy & Scratchy was first broadcast, then followed by Beavis & Butt-Head (1993), South Park (1997), also with its own cartoon within a cartoon Terrance and Phillip and the most recent Happy Tree Friends (2002), the cartoon has progressively taken the route of undermining its most consolidated narrative themes, which were determined by the intent to educate the public of children, or at least youngsters which seemed to be its natural target audience. This evolution was particularly seen in the West. Here, due to their "otherness" compared to the visual or narrative tradition, cartoons had been relegated to the sphere of childhood, as if they were nothing more than a stepping-stone to higher things. At best they might be surreptitiously enjoyed in a moment of nostalgia by some childish adult, along side other hobbies more suitable for his age. On the other hand, in Japan there are far fewer examples of this type of evolution due to the simple fact that anime, and in the same way before it manga, were a fitting continuation of the local artistic tradition. Because of this, cartoons were always considered "high" products, quite suitable to satisfy a mature and demanding audience. The limiting association between cartoon and children has simply never existed in Japan, whereas here in the west it was inevitable that there would have to be a backlash sooner or later.

Indeed there was a backlash and it suddenly exploded all the limits. What emerged is a sort of "counter-cartoon" marked by subversive roguishness and the portrayal of all imaginable transgressions of the "good rules." The subjects of the cartoons, which were previously characterised by a gentle innocence and educational intent, were dramatically overturned by foul language, demented humour, sex and sadistic and gratuitous violence. A spectacular short circuit was thus triggered between the bare-faced nastiness of the storylines and the delightfully childish cuteness of the images. It was exactly this short circuit which was used as the expressive driving force and was a powerful source of comedy, the kind of comedy which arises in perceiving such a problematical incongruity between two levels of experience (in our case between form and content): the mental energy evoked to bridge the gap is released as laughter once it becomes clear that the gap cannot be bridged. Needless to say the short circuit becomes stronger the more the cartoon drawings have a naïve and innocent appearance. So much so that there is a stylistic sequence in the progression of the Simpsons, South Park and Happy Tree Friends which could be roughly equated to the age of the audience intended for these images: primary school children, infant school children and children in the nursery.

There is a second level of reading which explains the psychological and behavioural degeneration of the cartoon heroes. Those same values advertised with pedagogical attention by traditional cartoons serve as a complacent mirror to a society which wants to see a reflection of bourgeois virtue and beauty, which wants to consider itself to be capable of distinguishing clearly between good and evil. The impeccable, shiny, plastic cover, which is protectively wrapped around the growth of our children, is the best possible tool to inoculate a certain life model and convince us of its goodness. However many of those children, once they grew up, became aware of the fact that this model was certainly not as good and innocent as it seems. A tumultuous destruction of icons followed which swept away the spotless cartoon heroes amongst others. The anti-hero Homer Simpson took their place, an incomparable symbol of the overturning of the self-proclaimed virtues of our society into vices. A similar path can be seen in artwork where the drawn character becomes central to the iconography. After Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami celebrated some characters from the media by reproducing them in a triumph of enlarged three-dimensional form, now the relationship with these characters has become much more suffered, subjective, even becoming a desecration. This is what Laurina does, in the good company of her many siblings: Yoshitomo Nara, Barry McGee, Chris Johanson, Taylor McKimens, the Royal Art Lodge, Dearraindrop and many others.

In one of her earliest works, You Are Infected, presented at the Galleria Civica di Arte Contemporanea in Trento in January-February 2005, Laurina invented a character called Bubo, who finds himself in a sequence of more or less narrative situations, following the most obvious serial rules of comics and cartoons. However in this case it was a character which, beginning with its name, was defined with such rudimentary lines and with such economy of construction that it was innately a parody, a denigration of every kind of "well made" production. Bubo captures the moment where the media icon was attacked by the underlying creativity and transformed into an antagonistic symbol, a symbol spread by the "barbaric" army of street artists, home-made fanzines and the on-line community. As if that was not enough, it is no accident that Bubo, with his black-hooded grin, is an evil virus, ready to attack- it is not clear if this attack is biological or computer-based, or perhaps an act of vandalism aimed at soiling the immaculate walls of the city.

An interest in self-portraiture also begins with Bubo, which is taken further in the following work, identifying the artist with her own creature. Thus was born The Amazing Pape, presented in the same year at the Galleria Perugi. We might find the source of inspiration in adverts for an energy drink which "gives you wings" for the super-paperina (super-duck), who is immediately identified as being a super hero by having her own special vehicle- the modified ready-made of a ""souped-up" three wheel Ape scooter car. Luca Vona commented at the time: "Just as Batman has the Bat-mobile, Laurina Paperina has the Pape-mobile."

We follow the adventures of the Amazing Pape in a series of extremely crude and primitive paintings and animations, which bring to mind the flickering bitmap images drawn by mouse, nonetheless wonderfully illuminated with vibrant and immaterial colours which flood in the instant we click on the paint bucket tool. The story sees our super-heroine beating up other super heroes in more or less improbable ways or else making fun of them, giving them inappropriate and completely trivial super powers.

In the works which followed, Laurina directed her wicked streak against other mass-culture icons, such as the stars of rock music or of contemporary art, who are undermined with bare-faced counterfeits and blatant fakes painted in the cycle Super-Fake, 2006-2007. Artists in particular come to a cruel end in the video series (How To) Kill The Artists and in The Artists-Bus, a wooden sculptural installation shown at Basel, both from 2007.

Meanwhile in all this work the feature which distinguishes Laurina from the most recent television animations is becoming clearer and which is the core of her originality. As I was quick to state at the start, it is only a superficial analysis which would lead us to identify her work with cartoons. Laurina certainly travels along the same path as cartoons for some of the way, and this is indicative of the "existential" difficulties that artists have to tackle nowadays: creativity is widespread, but not that produced by artists, but rather that of mass communication which owns the most powerful means of market penetration. In Laurina's case, however, this shared path only goes to a certain point before they take their separate directions.

We have seen how the ethical-social context and its achievements in awareness is a necessary backdrop for all of us. It is only fair to expect productions which aim at a certain credit to draw nourishment from the world we live in, managing in the end to brandish something which is indeed "ours". In order to do this one can chose more or less direct ways. The most direct is that practiced by cartoons themselves, more inclined to content which is referential and univocal. All the cartoons we have mentioned here, far from genuinely expressing the incorrectness that they are all too often accused of by simple journalistic criticism lacking the proper interpretive tools, they are in fact keen to express a precise "political" message. In these cartoons the element of desecration can be enjoyed in its own terms, but it is also instrumental to the objective of satire and declamation. Indeed we should not forget that Itchy & Scratchy appear in the Simpsons as an example of the worst kind of ruthlesness that television uses to capture an audience. If we enjoy their ferocity, we cannot ignore the underlying concept- it is through this and many similar cases that, day after day, with subtle insistence, consumerist, lobotomising alienation is perpetrated against your average family. The same can be said for South Park, where the children and their mischief are the last bulwark- if an unsteady one- against the respectable conformity which has transformed the adults into poor idiots. Even the splatter of Happy Tree Friends is far from gratuitous, rather it is an explicit rebellion against the great lie which would have us think that the world is as sugary as candy.

In contrast Laurina does not give us a moral at the end of the story. In her work the playful dimension is its own end, it is comedy and not satire. We can allow ourselves enjoy the action, the gags, the shapes and sounds without being forced at some point to go beyond this stage, to make it transitive in order to receive the message. There is no reason to see the destruction of Thor, flattened under the Pape-mobile as a statement for or against our society, rather it is an intransative fable satisfying in itself for its freshness and expressive purity. More or less as the adventures of Itchy & Scratchy would be if they were not framed in the ideological structure of the Simpsons, which leaves us a bitter taste in our mouth while we are laughing.

In this regard we should remember that it is an arbitrary idea that art should always have a deeply serious content directed at the exterior of its intrinsic responsibilities. Art with deep commitments is worth just as much as that without, or rather it is in an indirect way, which go through the elaboration of the formal and narrative plot, with the conviction of McLuhan that "the medium is the message". We now understand, for example, how unproductive was the old post-war dispute which set realism and abstraction in conflict in the name of a commitment which was ultimately shared by both parties, the difference being that one party openly operated in terms of surface and the other on a more hidden level based on the search for the profound structures of seeing and perceiving. As such we can say that Laurina, in the same way as abstractionists, does not want for anything if she manages to deal with the world we live in by not considering anything other than images, and without ever betraying the pleasure of the game.

All of this is wonderfully confirmed in Brain Dead, a phrase which an unfortunately austere viewer might scathingly utter against this artwork, but one which serves as a declaration of intent for a series of brilliantly "gratuitous" inventions. Furthermore it is a title which is also a homage to Peter Jackson's early films, masterpieces of DIY cinema, exemplary pieces for their courageous and radical refusal of any kind of dogmatic burden which stood in the way of the enthralling flow of the show. In these latest works Laurina portrays herself and many famous people with their skulls cracked open and their brains squirting out. This is the cruellest kind of torture inflicted on our mass-market superheroes, fitting of the worst kind of horror film. Much worse than the physical injuries is the moral injury caused by mocking obsessions, weaknesses and nervous tics which torment the people being portrayed. Their various and imaginative hang-ups are paraded, clearly stuck in plain view in the grey matter. However, the sense of crude horror, which could make the works unpleasant to look at, is successfully avoided by elegantly stylised graphic motifs emerging in particular from the way the brain is dealt with. The light pink clumps thus become decorative delights, aiming once again to exalt the pleasure of the show. Text by Guido Bartorelli

Opening on: 24.1.2008 at 6:30 pm

Siemens Art Lab

Dorotheergasse 12, Wien

free admission