Black Is, Black Ain't

dal 19/4/2008 al 7/6/2008

Segnalato da

Terry Adkins

Edgar Arceneaux

Elizabeth Axtman

Jonathan Calm

Paul D'Amato

Deborah Grant

Todd Gray

Shannon Jackson

Thomas Johnson

Jason Lazarus

David Levinthal

Glenn Ligon

David McKenzie

Rodney McMillian

Jerome Mosley

Virginia Nimarkoh

Demetrius Oliver

Sze Lin Pang

Carl Pope

William Pope.L

Robert A. Pruitt

Randy Regier

Daniel Roth

Joanna Rytel

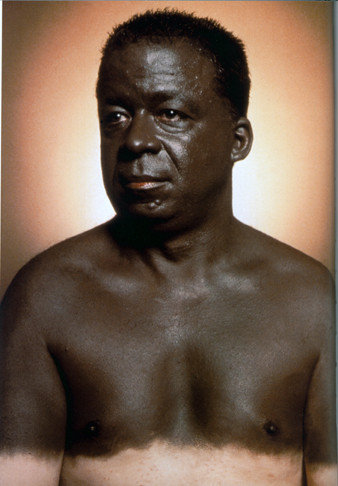

Andres Serrano

Hank Willis Thomas

Mickalene Thomas

Hamza Walker

19/4/2008

Black Is, Black Ain't

The Renaissance Society, Chicago

The exhibition explores a shift in the rhetoric of race from an earlier emphasis on inclusion to a present moment where racial identity is being simultaneously rejected and retained. The display brings together works by over 20 black and non-black artists whose oeuvre examines a moment where the cultural production of so-called blackness is concurrent with efforts to make race socially and politically irrelevant.

curator: Hamza Walker

Taking its title from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, this exhibition will explore a shift in the rhetoric of race from an earlier emphasis on inclusion to a present moment where racial identity is being simultaneously rejected and retained. The exhibition will bring together works by over 20 black and non-black artists whose work together examines a moment where the cultural production of so-called “blackness” is concurrent with efforts to make race socially and politically irrelevant.

Artists Include: Terry Adkins, Edgar Arceneaux, Elizabeth Axtman, Jonathan Calm, Paul D'Amato, Deborah Grant, Todd Gray, Shannon Jackson, Thomas Johnson, Jason Lazarus, David Levinthal, Glenn Ligon, David McKenzie, Rodney McMillian, Jerome Mosley, Virginia Nimarkoh, Demetrius Oliver, Sze Lin Pang, Carl Pope, William Pope.L, Robert A. Pruitt, Randy Regier, Daniel Roth, Joanna Rytel, Andres Serrano, Hank Willis Thomas, Mickalene Thomas.

Domino Effect

Race is one of the more disputed of life’s undisputed facts. But what kind of fact is race? Discredited as the source of any substantive biological difference, race has been reduced to formal visible differences that are no differences at all. In that regard, there is only a human race still troubled by categories of our own making; categories that have taken on a socio-political life of their own. Rather than an immutable framework belonging to a natural order, race, as a modernist construct par excellence, would depend on institutions and their ideological underpinnings for its form and content. Which is to say race is a concept of all too human proportion, one that arguably does not exist outside the dark and dubious ends towards which it has been put to use. Although a biological fiction, it remains a social fact whose history more than compensates for all that science disavows.

With respect to African-Americans, the public discourse on race is hardly suffering for want of incidence. A constellation of arbitrary events from recent memory includes the Don Imus affair; the trial of the Jena Six; the NAACP’s staged burial of the “N” word; the questionable distribution of hurricane Katrina relief funds; “Straight Thuggin’ Ghetto Parties” at The University of Chicago (where fun purportedly comes to die, a 187, no doubt); the ironic revelation that Barack Obama and Dick Cheney are eighth cousins; the not so ironic revelation that Al Sharpton is the descendant of slaves owned by the family of the late senator Strom Thurmond; the Supreme Court’s striking down of school integration plans in Louisville and Seattle; and last but not least, Obama’s presidential candidacy. Our so-called “obsession” with race reflects an anxious optimism insofar as race relations are a monitor of social progress. The dream bequeathed us by the Civil Rights Movement of being able to disregard an individual’s race entirely is as cherished as any constitutional ideal. As Obama eloquently noted in what is now referred to simply as “The Speech,” this dream makes the pursuit of a more perfect union anything but an abstraction. Transcending race, however, has proven a somewhat paradoxical task, one fraught with contention as our efforts to become less race conscious serve to make us more race conscious.

Yet, claims to racial identity have become suspect as the concept of race is irrevocably steeped in the rhetoric of biological difference. Critics such as Kwame Anthony Appiah instead favor the passage of race into culture, a notion which aligns itself with a Civil Rights era struggle for a group’s right to self-definition under cultural auspices. The reduction of “cultural self-determination” to the now pervasive term “blackness,” however, is antithetical to Appiah’s concept, as the “ness” implies that culture is an extension of skin color. Under these circumstances, “black culture” would represent the reification of race, in which case anything black people do is the precipitation of race. But more importantly, “blackness,” as an uncritical yet willful conflation of race and culture, stands in stark contrast to current efforts to make race socially and politically irrelevant. If the dismantling of affirmative action is any indication, then calling attention to race as the means to address inequality is considered at odds with the formal equality undergirding liberalism. To borrow a phrase from Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, “Black Is, Black Ain’t.” Using that as its title, this exhibition surveys a moment in which race is retained yet is simultaneously rejected.

Given that an exhibition of all African-American artists no longer passes for one about race, the discourse of race, as it resides in the visual arts in the broadest sense, is a very diffuse affair. Race is no less mercurial and complex as an organizing principle for an exhibition than it is a tricky issue in general. Just as one might ask what, one might also ask where is race.

Needless to say, figuration remains a staple for the representation of race as it is unimaginable without the body. Rather than projecting a secure sense of racialized identity, however, several of the artists in the exhibition problematize the skin’s ability to signify, resorting to disfiguration to deny easy recourse to the body as the locus of an essentialized self (Gray, McKenzie, Serrano). Conceived in terms of difference, race is not the province of a single group or individual. A notable shift since the watershed years of multiculturalism has been the emergent discourse of “whiteness,” which finds conspicuous expression in monologue-based performance/video work of a deeply psychological order (Jackson, Johnson, Rytel).

The reification of race is most apparent in the stereotype, a subject the likes of Kara Walker took up with a vengeance over a decade ago. Black is, Black Ain’t examines the stereotype in all the discrete objecthood of negrobilia (Levinthal) and at the conceptual level through text-based works of absurdist humor (Pope.L). This last description also applies to the other side of this poster designed by Carl Pope as his contribution to the exhibition. >br>

Along with class and gender, race forms a triad in which it is unable to be seen as an autonomous characteristic. The demolition of almost all of Chicago’s high-rise housing projects, including the infamous Cabrini Green and Robert Taylor homes (Good Times no more), serves as an extended meditation on the inextricable link between race and class. As icons of inner city poverty, these structures reflect race as dependent on if not produced through the structure of inequality (Calm, D’Amato, McMillian, Mosley, Pruitt, Roth). With respect to gender, the chief strategy to derail entrenched theories of biological determinism was to emphasize gender’s performative dimension. Staged photography and role-playing remain central to an investigation into the tropes of beauty, desire, and resistance (Nimarkoh, M. Thomas), with the upshot in one instance being the delightful reduction of race to camp melodrama courtesy of Hollywood’s use of passing as a plot device (Axtman).

There are also works that, for want of a better term, are just plain old soulful in their merger of style and content, as well as wit and poetry, where it is not only what you say but how you say it (Ligon, Pope, Arceneaux, Pruitt). Those works that partake of what might be called a “black aesthetic” find their ironic corollary in a strand of appropriation whose object is a black romanticism eternally frozen in the 1970s (Nimarkoh, Pang, H. Thomas, M. Thomas).

Last but not least, there is history. The reopening of the Emmett Till case in 2005 would question whatever closure the Civil Rights Movement achieved through its legislative victories. Rather than an exercise in nostalgia, several works in the exhibition portray the era of the Civil Rights Movement, and the Till case in particular, as sites of unresolved soul searching at the level of national identity (Adkins, Grant, Lazarus, Oliver, Regier).

By inseparably linking race and culture, the term “blackness” counters a notion of culture divorced from race as that split might downplay the extent to which race was institutionally formalized and the very real role race continues to play in shaping our society. Moreover, “blackness” bluntly begs that a distinction be made between race as the basis of discrimin-ation on the one hand, and solidarity as it is sought by a group already racially defined on the other. The latter might sound like a mise en abyme of sorts, in which the category creates the group that in turn creates the category etc., but it is more a domino effect, where a socially reproducible pattern acquires an inertia resulting in a concept that becomes its own cause, and effect, for that matter. As for transcending race, here we are, still somewhere under the rainbow where none of us is absolved from history. To put that in a positive light, we should take stock of where the discourse was sixteen years ago following the video-taped beating of Rodney King. Regardless of how you vote, you have to admit, watching history being made is better than watching it repeat itself.

Hamza Walker

Opening Reception

Sun, Apr 20, 2008 4:00 pm

There will be a talk with the artists, moderated by exhibition curator Hamza Walker, from 5 - 6 pm.

Renaissance Society

5811 S. Ellis Avenue Bergman Gallery, Cobb Hall - Chicago