Light

dal 30/9/2000 al 1/2/2001

Segnalato da

30/9/2000

Light

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

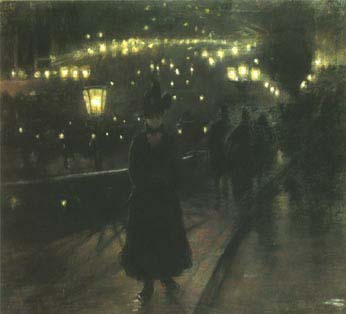

Art, Technology and society in the Industrial age 1750 - 1900. Since Antiquity, light has bathed every corner of the human imagination. Light symbolised the divine fire, the creative spirit, the fertility of the earth, the masculine principle of heat, and the victory over darkness. In the Renaissance the light of learning shone from the Academies, and came to represent divine intelligence; it was the language of the angels, the vehicle of inspiration, witness to the divine nature of Man.

Art, Technology and society in the Industrial age 1750 - 1900

Since Antiquity, light has bathed every

corner of the human imagination. Light

symbolised the divine fire, the creative

spirit, the fertility of the earth, the

masculine principle of heat, and the

victory over darkness. In the Renaissance

the light of learning shone from the

Academies, and came to represent divine

intelligence; it was the language of the

angels, the vehicle of inspiration, witness

to the divine nature of Man.

After the dramatic political upheavals of the 17th century,

light became secularised. Mechanised by Cartesian

mathematics and dissected by Newton's optics, light

became the subject of a muscular and nascent science,

committed to wresting Nature's secrets from her by force.

By the early 18th century, artists, scientists, philosophers

and industrialists were united by a common obsession with

light - an obsession that was to bear fruit in every field of

human activity. The first experiments with gas lighting were

conducted in the 1730s, the first electric light shone

tentatively and experimentally in the 1750s.

The ascendance of light was proclaimed on the frontispiece

of Diderot's great Encyclopédie in 1751, a year before the

invention of the lightning rod, powerful symbol of mankind's

mastering of the forces of nature. The rendering of artificial

light, and experimental science in general, came to captivate

such artists as Joseph Wright of Derby and his circle.

This obsession with light fuelled researches in industry as

well. In 1764 the Academy of Sciences in Paris announced

a competition on the best way to light a big city. Street

lighting was taken away from private property and

administered by municipal authorities.

It was no longer enough to show the way home - the path

itself was to be illuminated and made safe from highwaymen

and other hazards. In 1765, a coal mine manager in

Whitehaven lit his office with gas and offered to light the

streets of the entire town. But such light sources were still

fickle. Engineers and inventors tried to tame the faltering and

feeble light - and succeeded with the Argand lamp of 1784.

By the latter half of the century, the interest in light

nourished a rich foliage of images and an iconography using

light to champion progress, education, enlightenment.

Artists had always been slaves to light.

Now studies of different daylight situations, minutely

recorded, developed into autonomous works of art and

collectors' items.

Daylight classes were introduced at art academies. Light

remained a main concern of Romantic artists, who saw it as

the embodiment of spiritual qualities. Sacred or profane, light

was art.

Lighting changes were not immune to changes in taste: the

gaslight vogue was already satirised as early as 1807.

Gaslight had been introduced in some cities by the early

1800s, and on a grand scale in most big urban centres

beginning in the 1820s.

Street lighting became emblematic of urban modernity. All

kinds of merchandise was put 'on stage' under artificial light -

from hats and feather boas in brightly lit shop vitrines to

newly packaged and powdered 'ladies of the night'.

New lighting conditions changed the presentation of objects

of art in the museum, and the gaslight invaded the temples

of culture. As artificial light transformed the perception of

natural daylight, painting competed with ever more

sophisticated light-based popular forms of entertainment -

the diorama, stereo-photography, fireworks, projections.

Confusion reigned among artists as to the lighting

environment of their works - how would their paintings be

seen? The Salon and the exhibitions of the Impressionists

were open until late at night, and viewing conditions changed

dramatically - perhaps the artists should paint for artificial

light after all?

In 1888 Vincent Van Gogh had a gas-pipeline laid to the

Yellow House at Arles. But gas was not to prevail. A harsh

and unpleasant electric arc light was first introduced in 1861

in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and 'Electrical exhibitions' followed

soon afterwards, in the 1870s and 1880s.

By the early 1890s it was clear to all that despite its

aggressive aspect and its ugly spectrum electric light would

carry the day. The torch had been passed, and a new

century was waiting for a new light source. Science and

technology pushed ahead with innovation after innovation to

tame the undesirable effects of electric light, but could

artists keep up with such changes?

Manet was accused of not properly painting the white,

blinding electric light of the Folies Bergères. But where

Manet 'failed', others succeeded. By the end of the century,

the obsession with light that had dominated and transformed

life in Western Europe since the early 18th century rose to a

fever pitch as the century closed with a hymn to light - the

Palais de Lumière at the Universal Exposition of 1900, a

celebration of one hundred years of technological progress in

thousands of electric lights.

Curators

Andreas Blühm is Head of Exhibitions & Display at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. He

has curated numerous shows of 19th and 20th-century art, most recently 'The Colour of

Sculpture 1840-1910', and has published and lectured on the history of art from the

Renaissance to today and photography.

James Bradburne is director of the Museum für KunstHandwerk in Frankfurt am Main. He has

had creative responsibility for numerous award-winning exhibitions, including 'The Gates of

Mystery', 'Mine Games', and 'Merchants of Light: The Art and Science of Rudolphine Prague',

for which he was senior curator. Mr. Bradburne is also the author of numerous publications and

catalogues.

Louise Lippincott is Curator of Fine Arts at The Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. She

has published extensively on 18th and 19th-century art and has researched the use of artificial

light in 19th-century painting.

General information

The Van Gogh Museum is located on the Museumplein in Amsterdam, between the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk

Museum. The entrance to the Van Gogh Museum is at Paulus Potterstraat, number 7 The museum can be reached with

trams 2 and 5 from Central Station. The museum is easily accessible for the disabled. All floors can be reached by lift;

wheelchairs and buggies are available free of charge.

Addresses and telephone numbers

P.O. Box 75366, 1070 AJ Amsterdam

info: 020-570 52 52

tel: 020-570 52 00

fax: 020-673 50 53

Opening hours

museum:

daily 10-18.00

ticket office:

daily 10-17.30