Sites of Reason

dal 3/6/2014 al 27/9/2014

Segnalato da

Sol LeWitt

Richard Serra

Nancy Holt

Allen Ruppersberg

Seth Price

Simryn Gill

Liz Deschenes

Charles Gaines

Emily Roysdon

Matt Mullican

Hanne Darboven

Peter Downsbrough

David Platzker

Erica Papernik

3/6/2014

Sites of Reason

The Museum of Modern Art - MoMA, New York

A Selection of Recent Acquisitions. This exhibition brings together a selection of 16 works by 13 artists, that articulate relationships between ideas and the physical world, considering image, text, gesture, and voice as sites of exchange between aesthetic, conceptual, and political concerns.

MoMA presents

Sites of Reason: A Se

lection of Recent

Acquisitions,

an exhibition of 16 works by 13 artists, most

of which have been acquired over the last

few years and are on view at MoMA for the first

time, from June 11 to September 28, 2014. This

exhibition brings together a selection of works that articulate relationships between ideas and the

physical world, considering image, text, gesture, and voice—and hybrids of these—as sites of

exchange between aesthetic, conceptual, and politica

l concerns. The exhibition’s title is adapted from

the phrase “the sight of a reason,” from Gertrude Stein's groundbreaking prose work

Tender Buttons

(1914). In an ongoing project, Los Angeles–based artist Eve Fowler has reproduced fragments from

Stein’s writings in commercially printed posters originally displayed in public locations throughout L.A.

Stein’s aim to free language from its predetermined usage—and Fowler’s act of recontextualization—

provide a point of departure for the exhibition.

Sites of Reason

is organized by David Platzker,

Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, and Erica Papernik, Assistant Curator, Department of

Media and Performance Art, MoMA.

The exhibition draws connections between two ge

nerations of contemporary artists, including

Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra with Nancy Holt, Allen Ru

ppersberg, Seth Price, Simryn Gill, Liz Deschenes,

Charles Gaines, Emily Roysdon, Matt Mullican, Hanne Darboven, and Peter Downsbrough. The works

on view inhabit hybrid forms in which characte

ristics of drawing, video, text, performance,

photography, or architecture coalesce. As informat

ion migrates across a range of forms, possibilities

for interpretation expand, and questions emerge about the assumed role of the artist as singular

author.

The exhibition begins in the third-floor corridor

with a work by Simryn Gill (Singaporean, b.

1959). Using the printed word as source material, the artist often appropriates and transforms text,

raising questions about legibility and representation. For

Where to draw the line

(2012), Gill had five

essays she wrote over the course of a year meticulously typed out on a manual typewriter. The

resulting nine sheets of text are saturated, without

spacing, on scroll-like sheets of paper, overtyping

any errors and repeating the text as necessary to f

ill the space. The highly personal, lengthy texts are

enormous, densely printed, and virtually indecipherable.

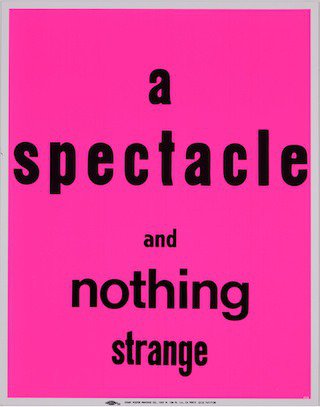

The exhibition continues down the corridor with Eve Fowler’s 21 posters,

A Spectacle and

Nothing Strange

(2012–ongoing), produced by the historic Los Angeles–based Colby Poster Printing Company. Known for its iconic mass-

produced signage, Colby's posters were used to widely advertise

concerts and events throughout L.A. for decades,

becoming a recognizable part of the city’s

landscape. Fowler has transposed Stein’s language

from the intimate experience of reading a book

onto the direct interaction with advertising in the public realm; the posters were originally placed in

public locations around Los Angeles, where one might

expect to see Colby ads. This is the first time

the posters have been displayed in a museum context.

At the end of the corridor is a late wall drawing by Sol LeWitt (American, 1928–2007) titled

Wall Drawing #1187, Scribbles: Curves

(2005). Based on the artist’s instructions, LeWitt’s works are

the result of a specific value system enabling the

expansion of written instructions into action and

material form. Unlike his earlier works that emphas

ized the flat plane of the wall, this work is

comprised of overlaying graphite scribbles that build six densities of grays into near black in bands,

which establish spatial depth. Formally, the work re

calls the rolling effect of an interrupted analog

video signal, suggesting a temporal dimension as well.

Next to the drawing is

Boomerang

(1974), a video made by Richard Serra (American, b. 1939)

with Nancy Holt (American, 1938–2013). In the wo

rk, originally broadcast over public access

television, Holt speaks as her words are fed back to

her through headphones with a one-second delay.

As her voice reverberates, or “boomerangs,” ba

ck, she states, “words become like things,”

disconnected from their individual meanings and from

a cohesive text. This interferes with Holt’s

thought process and establishes a distance between the artist and her own self-perception.

Featured at the center of the Special Exhibiti

ons Gallery is a pivotal work from 1974 by Allen

Ruppersberg (American, b. 1944) titled

The Picture of Dorian Gray. Transcribing the text from Oscar

Wilde’s 1890 novel over 20 panels, Ruppersberg attempted to “conflate reading and writing” through

narrative and visual form. In another layer, Wilde’

s book itself ruminates on art, as the ultimate

protagonist of the novel becomes a mysterious portrait painting with a metaphorical life of its own.

Ruppersberg’s meticulous hand-copying of Wilde’s text

speaks to his appreciation for the novel, while

translating the written word into a work for an audience outside the book.

Across from Ruppersberg’s work is Seth Price’s

Essay with Knots

(2008). A test in the

distribution of ideas and materiality, the work exists as a set of forms that contain a text titled

“Dispersion,” which explores the profound changes in

art and consciousness in the digital age. Using

different means of circulation that describe each other and become redundant—the physical artwork

itself, which takes on the form of individual page-like units lassoed together with ropes; a printed book available in stores; and a free PDF of the book

available on the artist’s website—Price situates

the artwork in different economic sphe

res, allowing for multiple possibilities of presentation that are all

“equally the work.”

For

Tilt/Swing (360° field of vision, version 1)

(2009), Liz Deschenes (American, b. 1966)

gives physical form to a concept illustrated in

a 1935 drawing by Herbert Bayer, “Diagram of 360

Degrees Field of Vision.” In this schematic, Bayer—a Bauhaus-trained graphic designer, architect, and

sculptor—conceived of a viewing situation breaking from the museum convention of hanging paintings on a wall; instead, his design allowed for works to be installed on all six walls of a room, including the

floor and ceiling. With

Tilt/Swing

, Deschenes has brought Bayer’s drawing to life using six

photograms—made using cameraless exposure to the

night sky and filled with subtly varying light

from the moon, stars, and surrounding buildings—sus

pended in a 360-degree aperture formation. The

photograms act as hazy mirrors, at once reflecting fragments of the changing environment back into

the work itself and onto the architecture in which it is displayed; their surfaces are left untreated, and

are intended to oxidize in response to shifting atmospheric conditions.

Conversely, a sculpture by Peter Downsbrough

(American, b. 1940) articulates space much

like a drawn line, calling attention to subtle shifts in its surrounding environment as it remains

unchanged.

Two Poles

(1974) is comprised of two opposing slim wood poles inserted into an

architectural setting. Since the 1970s, Downsbrough’

s modestly formed sculptures have reframed the

viewer’s perception of space and relationship to an artwork in such a space. In parallel with his

sculptural works, the artist has also created artist

s’ books and drawings that provide a more discrete

frame for his interventions. In addition to the four

drawings and the sculpture on view in the gallery,

Downsbrough’s work,

Two Pipes

(1972), has been installed in The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture

Garden.

The work of Charles Gaines (American, b. 1944)

often merges issues of cultural identity, race,

and social justice, as exemplified in his two-part work

Manifestos 2

(2013). Four large graphite

drawings present musical scores, each translated from historic texts of revolutionary manifestos—

including text from “An Indigenous

Manifesto” (1999) by Canadian activist and educator Taiaoale

Alfred, addressing the history and future of indigeno

us peoples; Malcom X’s last public speech in 1965,

in which he preaches for harmony among religions; Raul Alcaraz and Daniel Carrillo’s

“Indocumentalismo” (2010), which calls for rights for undocumented individuals; and the “Declaration

on the Rights of Women,” written by Olympe De

Gouges in 1791, championing equality among the

sexes. Gaines has created an operatic performance for each of the scores—using each letter’s

corresponding musical note and the spaces as musical pauses—which play on accompanying video

monitors. As the manifestos act individually and together, Gaines considers the multiplicity of identity

and the ways in which the activist content of these texts become—sonically, emotionally, and

intellectually—complicated by the affect of music.

With the two-channel video work

Sense and Sense

(2010), Emily Roysdon (American, b.

1977) considers the ways in which political movements are represented within a broader

interpretation of choreography as organized move

ment. For this work, Roysdon collaborated with

performance artist MPA, whose own work examines th

e personal and political implications of the body

in space. MPA walks on her side in a 90-degree va

riation on the everyday gesture, her body pressed

to the ground, through the Sergels torg pedestrian

plaza, Stockholm’s buzzing central square and the

site of countless political demonstrations. MPA’s physical struggle to appear upright recalls the illusion

of free speech and movement embedded in the site and emphasized through its formal abstraction.

Further, the everyday movement of passersby is rela

ted to traces of theoretical or political movements

galvanized there.

Since 1977 Matt Mullican (American, b. 1951) has used hypnosis in his artistic process, which

he considers a conceptual strategy for breaking pa

tterns of everyday life in order to expose the

underlying structures of his subconscious. Work

ing in this altered state, Mullican becomes

that person,

an ageless, sexless being that is a passenger inhabiting his body. In performance-like fugues,

that

person

crafts artworks while talking to himself through a haze of hypnotically induced intoxications or

psychosis.

Untitled (Learning from That Person’s Work: Room 1)

(2005) is a large-scale manifestation

of such a work. This disorienting, maze-like installation is crafted in 12 parts, in which bed sheets,

each covered with nine collaged ink-on-paper dr

awings, become interior walls between which the

viewer traverses. An accompanying video componen

t adds dimension, and Mullican’s voice, to the

installation.

While living in New York City from 1966 to 1968, Hanne Darboven (German, 1941–2009)

developed a painstakingly organized iconography of

systems of choreographed lines, producing a

rhythmic cadence which is visible in this untitled work from around 1972. Darboven worked in near

isolation during her time in New York, but did befr

iend fellow artist Sol LeWi

tt, with whom her work

shares an intellectual and formal relationship. Both artists dealt with the manipulation of systems as a

visual style.

The exhibition is supported in part by The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern and by the MoMA Annual Exhibition Fund.

Press Contacts:

Paul Jackson, (212) 708-9593 or paul_jackson@moma.org

Margaret Doyle, (212) 408-6400 or margaret_doyle@moma.org

Press Viewing: Wednesday, June 4, 2014, 9:30-10:30 a.m.

Special Exhibitions Gallery, third floor

The Museum of Modern Art MoMA, 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019

Hours:

Saturday through Thursday, 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Friday, 10:30 a.m.–8:00 p.m.

Museum Admission:

$25 adults; $18 seniors, 65 years and over with I.D.; $14 full-time students with current I.D. Free, members and children 16 and under. (Includes admittance to Museum galleries and film programs). Free admission during Uniqlo Free Friday Nights: Fridays, 4:00–8:00 p.m.