L'edicola digitale delle riviste italiane di arte e cultura contemporanea

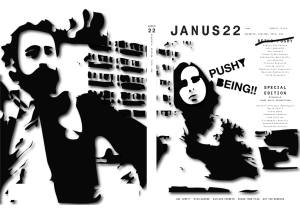

Janus (2006-2010) Anno 8 Numero 22 giugno-dicembre 2007

The Biennale Syndrome

Carolyn-Christov Bakargiev

anywhere, anytime, here, now

BEING PUSHY

COSMETICS, COSMOLOGY

AND BEING PUSHY | p. 3

Why the phenomena related to pushiness should be

studied by a new discipline: pushyology.

By Nicola Setari

MAKING SENSE OF SCIENCE | p. 11

Marleen Wynants meets Evelyn Fox Keller, an

eminence grisein the practice and philosophy

of science.

JAN LAUWERS & NEEDCOMPANY

RADICAL BETWEEN HEART

AND REASON | p. 17

RADICAAL TUSSEN HART EN REDE | p. 24

Restlesness does not necessarily imply pushiness:

an essay on Jan Lauwers’ work by Luk Lambrecht.

NOT FOR SURVIVAL ONLY | p. 29

NON DI SOLA SOPRAVVIVENZA | p. 34

Tiziana Migliore sets out in the colorful jungle of art

and nature on the discovery of different intrusive

strategies.

PUSHY WARS (E) | p.39

PUSHY WARS (N) | p. 45

Battle-field specialist Luc Derycke elaborates on

the rise and fall of pushy wars.

OEDIPAL EPISTEMOLOGY | p. 53

EPISTEMOLOGIA EDIPICA | p. 56

Behind every revolutionary scientist

there’s an insistant mother,

at least according to Massimiliano Cappuccio.

ME, MYSELF AND MY AVATAR | p. 60

MON AVATAR ET/EST MOI | p. 65

Maria-Cristina Ferraioli

goes on an art expedition in Second Life.

OCCHIO REALE (E) | p. 70

OCCHIO REALE (I) | p. 74

Alessandro Bertolotti offers a surprising insight

in the variety of exhibitionist types

by constructing a very visual game.

ARTE DE CONDUCTA | p. 79

What happens when artists run the school?

Francesca di Nardo interviews Tania Bruguera

on the subject of her art school in Havana.

THE INTRUDER AND ITS IMAGE | p. 84

L’INTRUS ET SON IMAGE | p. 88

Riccardo Venturi takes a sentimental journey

in the transplant diaries of philosopher Jean Luc Nancy.

IS THERE ANYONE? | p. 91

WIE GAAT DAAR? | p. 93

L’Intruseof Maurice Maeterlinck

works its literary way into the new Janus.

Special Edition

II

THE BIG EXHIBITION

The biennale syndrome | p. 2

Carolyn-Christov Bakargiev

Around the world in 28 biennials

| p. 6

Il giro del mondo in 28 biennali

| p. 6

Francesca di Nardo

d’Après Venise | p. 11

Luigi Di Corato

Interview with David Croff | p. 20

Robert Storr’s Biennial | p. 22

La Biennale di Robert Storr

| p. 22

Maria Vittoria Martini

The BN project:

La biennale delle biennali | p. 29

Emmanuel Lambion

A place you have never been before

| p. 37

Vessela Nozharova

Floating Territories | p. 45

Towards documenta 12.

L’architecte est absent | p.49

Frank Maes

Making space for silence:

MARTa’s challenge | p. 64

The Paris Biennial, 2006 – 2008

La Biennale de Paris, 2006 – 2008

| p. 68

Elisabeth Lebovici

III

IN MEMORIAM: SOL LEWITT | p. 3

GANDER_OBRIST

Back to the future | p. 11

VERMEIR_VAN BELLINGEN

Katleen Vermeir, a succinct stratigraphy

of special friction | p. 19

Katleen Vermeir, beknopte stratigrafie

van de ruimtelijke frictie | p. 24

YONG PING_PARISI

The retreat of the gods | p.30

Le retrait des dieux | p. 36

Picturing Healing: Mitchell’s Autoimmunity

Nicola Setari

n. 25 giugno-dicembre 2010

Pedro Cabrita Reis, True Gardens

Giovanni Iovane

n. 24 giugno-dicembre 2008

A question of time frame

Tobias Kokkelmans

n. 23 gennaio-giugno 2008

Fotografie erotiche di fantasmi, fate e presenze invisibili

Alessandro Bertolotti

n. 21 gennaio 2007

20100, Milano, (I)

Francesca di Nardo

n. 20 giugno-dicembre 2006

Geografie immateriali

a cura di Giovanni Iovane

n. 20 giugno-dicembre 2006

Big biennials? Baby biennials? Banal biennials? What is the “biennale syndrome” that seems to have taken over the art world and the world at large over the last fifteen years? Why and to whom are Biennales so attractive? Why are they also so unattractive for some audiences?

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, interested in contemporary art and historical avant-garde, is artistic director of the 16th Biennale of Sydney (2008) and chief curator at the Castello di Rivoli museum in Turin.

From a general perspective, beneath these events lie political imperatives, struggles and the negotiations and transformations of a global economy of interrelated cities.

The rise of biennales (and other periodic international exhibitions) has decentralized art and has created multiple art systems. It has provided a platform for artists from what used to be called “peripheral areas” of the world to practice and enter into the conversation of contemporary art. It has decreased the legitimizing powers of the old “centers” and this has been a healthy world development. Artists are often actively partaking in political struggles, and international exhibitions such as biennales have provided a place where these conversations can be articulated.

At the same time, the new emerging network of biennales is also disempowering. It is one of the causes behind the weakening of other alternative forms of artistic self-organization, which now risk being accused of elitism alongside the new “public success” of contemporary art that is breathtaking today and of which the biennale system is a part. This is a form of success that tends to marginalize some of the most refined and serious artistic research.

Basically we need to deal with the pros and cons of cultural populism.

The accelerated increase in biennale events since the early 1990s runs parallel to the rise of the internet, to the multiplication of art fairs and generally to the prominence of contemporary art as a shared idea today. There is an impulse to turn art into something very popular, visible, consumable, accessible (accessibility is a key word of the internet society), into the highest form of popular culture. Art becomes the ultimate object of communication at a time when communication itself has become the ultimate object of consumer culture. We are in a Google-scanning and Wikipedia age where knowledge is readily available because of the immediacy of the internet, and the collaborative nature of the net, yet for these same reasons this is often superficial knowledge.

There are more than one hundred biennales in the world today, and every city seems to be planning one. As this phenomenon grows around the world, it is also increasingly fashionable now in Western circles to criticize the “new biennales" - saving only the oldest and thus the most DOC (to borrow a term from the Italian wine industry) European and American periodic exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale, the Carnegie International and documenta in Kassel. This is a typically conservative attitude dictated by fear – fear of losing power. Many high-brow museums in New York (I have experienced this directly) even send letters of rejection upon the request of loans solely on the basis that they "do not lend to biennales" - as if the simple fact of being a “biennale” would imply the exhibition is curated superficially and quickly, or that the venue is certainly unsound and inappropriate from a conservator's perspective. This occurs independently of whether or not the biennale is hosted in museum venues with high standards of conservation and facilities, and independently of the intellectual rigor of the proposal. These same institutions however, have begun to lend works to private commercial galleries for what they feel are instead highly “curated” exhibitions. What are the latent reasons for all this? What are the fears and the desires of our troubled times?

Are we all very confused?

The same people who criticize the “biennale syndrome” rarely criticize the rise of the art fairs and auction houses that has run parallel, with every big city in the world attempting to become a center of the art market. Since the mid-1980s when ARCO Madrid set up special programs, art fairs have been competing directly with biennales for cultural prominence as global platforms, by initiating and developing more and more experimentally “curated programs”. Newspapers and art magazines now discuss and compare the latest Art Basel to the latest Venice Biennale. The boundary between the art fair and the Biennale is thus blurring in some instances. Yet few critics are noticing that the art fair model is also eroding the singularity of the curated exhibition and the individual's ability to hypothesize and construct knowledge: the fair is indeed a celebration and an expression of pure cultural relativism - a multiplicity of positions (each booth) happily juxtaposed in the democratic space of the “free market”.

On the one hand we are witnessing a trend of “biennale-bashing”, in favor of exclusivity, wealth and status, while on the other, more and more cities around the world look at Venice, whose biennale started in 1895, or São Paulo (1951), Sydney (1973) and the more recent Istanbul (1987) and Gwangju (1995) as examples to follow.

The image of a city is “vehicled” to its own local population through a biennale, and also “vehicled" to the world, far from the location where the biennale actually takes place. This occurs through the catalogue, the e-flux announcement, the word-of-mouth. Sharjah for example has been put on the map by the few biennale editions it has hosted.

Biennales are thus attractive to city planners, investors, local politicians and reformers from many walks who want to develop their cities and educate people through art, as well as support tourism and foster a local identity.

Similarly, for progressive and socially-minded politicians, there is a wish to use art as a tool for democracy and peace. A space of dialogue that might reduce social conflict by creating experiments in community building: the biennale as a locus and model for a “happy community”. Art is to be a form of public education, for the widest possible audiences.

Indeed, art in late consumer culture carries huge symbolic value as a catalyst for collective identification and as the ultimate sphere of desire - to desire and consume that which is most useless, and that which may hopefully carry by its “mystery” some aura previously constituted in the sphere of religion and belief.

There is thus a strange and unexpected alliance that has been forged. The investors and tourist industry are joining with progressive politicians and those who believe in the social role of art.

In other words, a double and contradictory movement has occurred. On the one hand, there is a healthy decentralization of the art world and multiplication of art centers that runs parallel to a thematic focus on socially relevant topics of most recent biennales (justice, ecology, contact zones). On the other hand, a loss of intellectual freedom (the freedom that comes with being part of revolutionary avant-gardes rather than mainstream culture) and a surprising amnesia of linguistic awareness - a loss of awareness that language itself is political. Because a broad audience has to “understand” contemporary art, the crucial nature of contemporary art is denied - its ability to break paradigms, to break language, to contradict consensus, to be radically “other” from society at large, to create and experiment different ways of presenting itself.

Because of all this, biennales and indeed public group exhibitions generally, or even public art projects, are often unattractive to many radical artists who feel that their research is being used as a promotional tool for purposes far from their own deeper motivations. This is because art has become “successful” and a tool of propaganda in more and more contexts, thus eroding its avant-garde and revolutionary potential, its negativity and its critical power. While in the late 1960s and 1970s, contemporary artists began to work outside of institutions and the “white cube” as a way of anarchically disrupting the boundaries between art and life, and high and low, thus initiating context-specific art and public art. Today public space - the “outdoors” - has become privatized over recent years to the point that art is being used to decorate, to gentrify and “aestheticize” (and anesthetize) corporate public arenas in many cities. Rather than provoke questions and disrupt accepted conventions, art is used to create consensus and control populations.

It is interesting, however, to “psychoanalyze” the biennale syndrome, rather than only analyze it as a social phenomenon. What domesticates culture most? Rules and structures do. Curatorial practice consists of creating models of experience, dispositifs through elements that stake-out a position on the level of the language of presentation that coincides with the basic tenets and positions of the art one is exhibiting. The form of the exhibition repeats and reiterates the position that the curator chooses to align and agree with in terms of how we could construct or should construct knowledge – the politics of aesthetics we choose to agree with.

Curating, therefore, is not a neutral endeavor. If, for example you express a politics of disagreement with the consumer culture of globalization through the selection of artworks you include (and you believe in artworks that enact a resistance to this mediatization and flattening of life in a world where “economics” is the only value) then it is absurd to take artworks that in their own discrete experience suggest this critique and create an exhibition where you juxtapose them, one after another, in a way that neutralizes them – as if they were each expendible and substitutable. If you do this, you are only repeating on the level of the experience of the exhibition as a whole, the same problem that exists in real life and that the artist is dealing with. Thus you are subliminally denying the political stance that you appear to want to embrace on the level of the theme of the exhibition.

The language of exhibition-making must be the same or in relation to the language of the artworks you choose to display or set in conversation with each other.

Biennale means “every two years”. The term itself denies any possibility of a radical and absolute statement, just as it denies any possibility of creating something unexpected. If a biennale occurs every two years, then it is not unexpected. Also, if one curator says something this time, another will say something else in two years time, so not to worry, we can take his or her statement with a grain of salt, we don't have to take it that seriously after all. Thus it is the etymology of the term biennale itself, which expresses the dilemma: the periodicity and temporal regularity of the nature of the event is the problem: it is an extreme form of relativism that cannot but flatten uniqueness, difference and singularity. No curator can ever make an absolute statement in any biennale. To create a temporal structure, like a television series, means to deny that any edition of any biennale can be revolutionary. So the problem of the “biennale syndrome” in the end is cultural “relativism” itself, and there is a strange alliance now between the late postmodernist intellectuals who aspired to introduce cultural relativism and the market economy that can thrive only on relativism, maintaining the status quo by confirming itself through the institutionalization of difference.

The question today is how not to be contemporary, how not to make a festival, how not to communicate, and yet somehow manage to deliver the event. For a curator today, to make a biennale means to learn from artists how to navigate this misunderstanding, how to create an exhibition with them as a decoy, how to open up spaces of revolt with them, how to deny, while celebrating them.